The analytical chemist who runs a preeminent Japanese research institute discusses her childhood in Sweden and how she came to chemistry

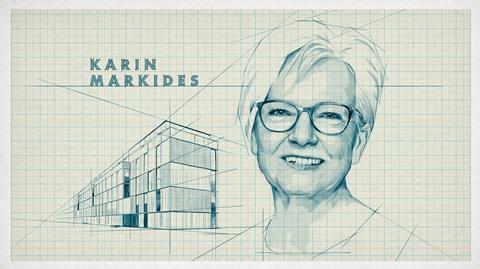

Karin Markides is an analytical chemist who recently took over as president and chief executive of the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology in Japan – the first woman to head that institution. Her past duties have also included deputy director general of the State Agency for Innovation Systems in Sweden, and chairman of the board of Johanneberg Science Park in Sweden. In addition, Markides has been involved in selecting the Nobel prize in chemistry, as a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences’ class for chemistry.

I grew up outside of Stockholm, Sweden, in a little town. It really was a very beautiful landscape, with rift valleys and lakes. Like a postcard.

My father believed that it’s very important for children to take care of animals so that they can learn to be good leaders. We had a hobby farm with different kinds of animals – there was a horse, a pig and little chickens. We didn’t sell them for meat or eggs, it was just for our family.

My family was more focused on entrepreneurship than education. Where I grew up, hardly anybody went to university. My sister and I were the only ones in our family who attended university. My brother did not. There were so many other opportunities, so it wasn’t that people didn’t have the drive, but they often focused more on entrepreneurial things.

I was always encouraged by my father to explore possibilities that could take me out of that town and then maybe come back later. He didn’t want me to stay there all my life. He wanted me to be braver and do things that were different.

Growing up, I was always constructing and painting. I thought that I wanted to take over my father’s company – he was an architect and builder, and I was with him a lot, helping. After high school, my father encouraged me to move to Stockholm.

My father just dumped me in the centre of Stockholm with a bicycle, and that was it. I didn’t know what to do, I had to get a map and try to get to know the city. Slowly, I came to really love it.

I loved mathematics and started to study that at Stockholm University. But the people in the maths department were sort of narrow. Maths was kind of isolated from the other disciplines.

From maths, I jumped over to nature/geography. I did research on the glaciers up in the north, and some water balance studies on forests, and that was great fun. I learned a lot about the world. But then I wanted to understand things more on the molecular level, and decided to get a second undergraduate degree in chemistry. That is when I found analytical chemistry, which is a true passion.

There was nobody to compare me with, so I wasn’t put into a box

With some scientific disciplines it’s like learning a new language – you have to learn a lot of theory and the chemistry language before you can start to enjoy and really use it.

Chemistry has a lot of relevance to society, as you can observe the same phenomena arising in the molecular world. Chemistry is all about interactions and catalysis, which you also have in the visible world.

I was already a mother with two boys when I decided to start graduate school. A professor at Stockholm University said to me, essentially: ‘We don’t have really have any women in graduate school, and of course because you also have children that’s not really going to work.’ So of course, I made it work. That just encouraged me.

I didn’t follow the rules. As a PhD student, I was connecting a lot with industry and with other disciplines. That wasn’t so appreciated by others who thought that you should stay in your discipline, remain in your lane.

As a postdoc at Brigham Young University in Utah, I was a minority – not only as the only woman, but also as the only European and non-Mormon in chemistry. But that did not scare me, I got all this freedom. There were no borders, nobody to compare me with, so I wasn’t put into any kind of a box and could actually explore more.

My peers have always treated me well, and I never felt that I was less than, or shouldn’t be included because I’m a woman.

Knowing what I know today, if I were starting my career over, I would change absolutely nothing. To learn chemistry when I had this experience in maths, and also of nature, was perfect because I learned it with a lot of interest and could get the theory with a lot of joy.

Outside of work, I have always enjoyed nature. I also paint when I have a chance and have managed to get in some architecture and building houses. I have designed a house in Greece and a couple of houses in Sweden, then worked with builders to build them. Our base is in Sweden, in the house where I grew up that I rebuilt. That’s kind of a circle there.

Nature and painting open me up totally to new thoughts. Here in Okinawa, you can snorkel and see all of these fantastic corals, and that cleanses your brain totally – it’s perfect.

1 Reader's comment