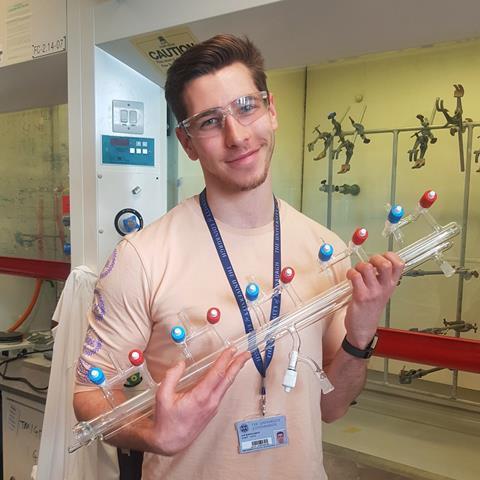

Andryj Borys shares his knowledge on air-sensitive chemistry through an open-access handbook and website

Andryj Borys saw a Schlenk line for the first time when he started his PhD. Soon he realised that using it well required very specific skills that, like dark magic and traditional family recipes, seemed extremely secret – passed along by chemists for generations. The few books on the subject were often outdated and behind paywalls, so Borys decided to take action: based on his own lab notes and drawings, he created the Schlenk Line Survival Guide and shared it online for free.

The project began a few years into Borys’ PhD at the University of Kent. ‘My supervisor, Ewan Clark, started teaching me lots of useful techniques, and I decided to keep detailed step-by-step records,’ he explains. The lab treasured them and used them to teach other students. ‘This really encouraged me to create something more thorough, and make it available to help others,’ adds Borys, who is now a postdoc at the University of Bern in Switzerland. Three years after his first encounter with a Schlenk line, he published the guide online. ‘Since April 2019, the website has received over 100,000 views!’

Get set… cycle!

As Borys explains on his website, a Schlenk line is an essential piece of lab equipment to manipulate compounds that are sensitive to air and moisture. Each line has two manifolds, one connected to a vacuum pump and another linked to a source of dry inert gas – normally argon or nitrogen. To carry out air-sensitive experiments, chemists connect their glassware to the Schlenk line and ‘cycle’ them to ensure they’re completely free of oxygen or moisture inside. The name of this procedure comes from the series of cycles of vacuum and inert gas needed to ensure the perfect conditions.

As well as basic operations like setting up the Schlenk line and ‘cycling’, the guide covers more complex procedures, such as cannula transfers, setting up reflux reactions under inert atmosphere and preparing NMR tubes of air-sensitive samples. ‘I don’t believe people purposely reserve their own tips, tricks and procedures,’ explains Borys. You could find how-to videos and short guides around the internet, he says, ‘but there was a clear need for a platform to gather and share them.’ The popularity of the guide – which was recently translated into Spanish – shows this necessity was real. Borys constantly receives positive comments from students and professors: ‘[They] illustrate the importance of having a guide like this,’ he says.

The Survival Guide has now grown into a 60-page comprehensive document that, beyond procedures, includes information about equipment and a short section about gloveboxes. Throughout the handbook, the attention to detail in both the instructions and illustrations makes it a valuable reference even for chemists who are just starting to work with air-sensitive products. ‘As an undergraduate, air-free chemistry seems quite intimidating,’ says Hayley Russell, who was one of the first readers of Borys’ guide when she was studying at the University of Edinburgh, where Borys did his first postdoc. ‘It was nice to have something very detailed to refer to.’ In fact, Russell is now going back to the lab after a few years of office work, and she’s been consulting the Schlenk Guide ‘to refresh [her] memory of air-free techniques’.

Chemists should be transparent [describing] their experimental methods

Following open-access principles, Borys has published everything under a Creative Commons licence that allows free distribution, as long as the author gets credited. ‘He made the guide because he wanted to help people,’ says Russell. Furthermore, information behind paywalls hinders scientific progress in developing countries. ‘Chemists should be transparent [describing] their experimental methods,’ Borys adds. If anybody needs to follow the same procedure in the future, clarity and thoroughness will make their lives much easier!

On top of instructions on how to use Schlenk lines, the Survival Guide webpage also includes synthetic procedures and ‘recipes’ to prepare common reagents in air-sensitive and organometallic chemistry. These include techniques to purify lithium-aluminium hydride and step-by-step instructions to make the perfect potassium mirror.

Lined up

In the future, Borys would like to focus on the uses of the Schlenk Guide in chemical education. ‘I would like to create guides and experiments that can be incorporated into undergraduate laboratories to introduce students to Schlenk line chemistry,’ he says. Russell sees great potential in this idea and suggests that ‘the addition of little quizzes’ to assess students’ comprehension ‘could have potential as a pre-lab exercise for teaching.’

Borys would also like to explore educational videos, but as a postdoc time is a precious asset – recording, editing and promoting content is an exhausting endeavour. ‘Once I become an independent researcher […], then I will for sure begin making YouTube content,’ he says.

Borys would also like to explore educational videos, but as a postdoc time is a precious asset – recording, editing and promoting content is an exhausting endeavour. ‘Once I become an independent researcher […], then I will for sure begin making YouTube content,’ he says. In the meantime, the Schlenk Guide website links to some of the webinars he’s hosted in the past few months, such as an episode of ‘Synthesis Workshops’ – a channel on chemical synthesis pioneered by another postdoc, Matthew Horwitz from the University of Oxford.

Borys plans to keep developing his guide, concentrating his efforts in adding new synthetic procedures and exploring the possibilities in education. Moreover, he is always open to receiving contributions from other chemists: ‘Things are much better when shared!’

No comments yet