Interactive science communicators make a difference while having fun

When Jonathan Frederick was in elementary school, he would often tag along with his father, a software engineer, to the local science museum. As his father helped the programmers there with computerised exhibits after work, Frederick frolicked around the empty building for several hours at night. ‘It absolutely made me fall in love with museums,’ says Frederick, who has worked as a science communicator at several museums and is now the director of the North Carolina Science Festival in the US.

Some science enthusiasts fall in love with research and devote their careers to academic pursuits. Others, like Frederick, find meaning in making the subject accessible to people. Interactive science communicators do important work. For them, though, that work is also endless fun.

A love of science, but not academia

Unsurprisingly, many interactive science communicators possess a science background, though it isn’t necessarily a requirement for this type of work. Frederick enjoyed studying science in college but never wanted to be a scientist. Instead, he ‘found that there is real value in being an ambassador for people who are really comfortable in labs and who may be not quite as comfortable speaking out in public’.

Emily Fisk, who works at the Science Oxford Centre, an interactive indoor–outdoor science education centre in Oxford, UK, realised that she wasn’t cut out for the tenure track while pursuing a PhD in medicine. She loved lab work, but the politics of academia and a difficult relationship with her supervisor propelled her to explore alternative careers. In her spare time, she started taking part in science festivals and discovered she loved communicating science.

It is the surprise and the joy they get, and that kind of little spark you see

At the Science Oxford Centre, which is run by Science Oxford, part of the Oxford Trust charity, Fisk facilitates and organises visits, shows and workshops for families and schools. ‘I love the school visits more than anything,’ she says. ‘Every now and then you’ll say something or do a demonstration and you’ll see one or two children go: “What?!” It is the surprise and the joy they get and that kind of little spark you see. I love those little moments.’ Fisk adds that she is fortunate to have found a job that combines teaching and public engagement. ‘I’ve got the perfect career,’ she says. ‘I’m a basically a teacher, but also I don’t have the pressure of teaching.’

Similarly to Fisk, extroverted Stacey Baker, a public engagement programme associate at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), left academia after spending three years in a molecular biology lab at the National Institutes of Health in the US. ‘I realised research wasn’t exactly for me: it was fulfilling for my analytical brain, but not for my creativity or my wanting-to-connect-with-people side,’ says Baker.

Jeff Vinokur forayed into the field fairly early on. While still an undergraduate student, the PhD-level biochemist launched the Dancing Scientist programme, travelling around the US to perform visually appealing chemistry and physics experiments for school children – with some dancing thrown in. ‘When you make things change colours, that kind of stuff is very engaging to a child,’ says Vinokur, referring to his demonstrations. ‘It can inspire them and influence them to consider a career in science and be more interested in science.’

Now a full-time science communicator, he established Generation Genius, a company that creates educational science videos for children aged five to 13, in 2018. Around one million students consume the content each week. While Vinokur plans to get back to research at some point, right now he is totally committed to the cause of inspiring children. ‘I’m not of the belief that everyone needs to be a scientist, but I do think that everyone should be exposed to [science] at the right age, and then they can decide what they want to do for themselves,’ he says.

Serious work follows the fun

While interactive science communicators get to enjoy many playful activities during a workday, they also have their work cut out for them. Being an entrepreneur, Vinokur inevitably ends up wearing a lot of hats. Not only does he have to appear in front of the camera, he also has to assist with writing scripts, video editing and admin work. ‘On one hand, it’s exhausting,’ says Vinokur. ‘But on the other hand, how lucky am I to have this type of career to be reaching one million students every week.’

Fisk’s job keeps her on her toes as well. She is one of two people at the Science Oxford Centre who coordinate and run the school and public visits. ‘I have to switch very quickly between sitting at the desk and sorting out all the logistics to performing a show,’ she says.

Moreover, communicators have had to adjust and adapt quickly to the pandemic. Like many museums, the Center of Science and Industry (Cosi), in Columbus, Ohio, US, shut down at the start of the pandemic. Amid the crisis, Frederic Bertley, president and chief executive officer of Cosi, and his team brainstormed ways to reach out to the public. ‘We know that people love coming to a science museum because of the hands-on interaction. It’s not quite like the art museum where you stand and just look at the art,’ says Bertley. ‘So, my challenge to the team was how do we do that? How do we preserve what people love about Cosi, [even though] we’re physically closed?’

Bertley’s team created six science kits, each revolving around a theme (such as space or the human body), and started distributing them to underprivileged children. They aim to reach 100,000 children in the US by end of the year. Each kit has materials for five different hands-on activities.

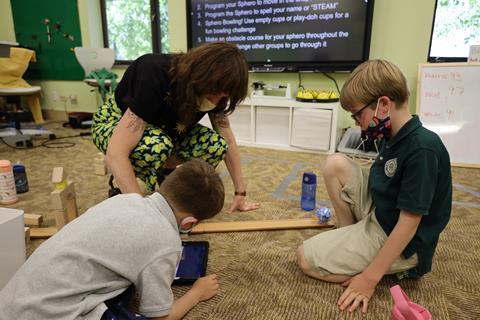

Meanwhile, Katie Behrmann, a Steam and Innovations educator at Aspen Academy, a private school near Denver, Colorado, US, had to find new ways to teach her elective – an interdisciplinary subject that combines robotics, engineering, coding, building projects and sustainability. At the start of the academic year in August 2020, the school implemented a hybrid model of attendance – students could either study at the premises with Covid protocols or virtually.

For the virtual learners, Behrmann used her instructional design chops to create simulations online, so students could participate in the same kind of design and tech challenges that others at the school were doing. For example, if their classmates were learning clay modelling, web-based students would use 3D modelling programs online. ‘Being able to really explore these online platforms was a real boon for students both in-person and online,’ says Behrmann. ‘It was really interesting to be able to compare making a prototype of something physically and then making it online or in a digital space … kids as young as seven or eight were able to talk about physical versus digital modes of fabrication and engineering.’

From science to science communication

In a world plagued by misinformation and fake news, it’s imperative for scientists to educate the public. But busy academics are often unable to devote time to this cause – and that’s why the work of career science communicators and educators is so valuable. ‘We create meaningful connections between researchers and public audiences,’ says Holly Menninger, the director of public engagement and science learning at Bell Museum at the University of Minnesota, US. ‘There’s lots of reasons why those meaningful connections are important. One is that science is so critically important to our health and well-being and the environment and [we make] sure that public audiences are able to ask questions and have the information that they need to make decisions.’

People with science degrees and research experience are well-suited for this profession because their background equips them with several advantages. Menninger, who has a bachelor’s degree in biology and a PhD in behaviour, ecology, evolution and systematics, notes that her degrees give her ‘a really strong foundation in the process of science. I can explain how we know what we know because I’ve done it, and I’ve been part of that process.’

Scientists also find it easier to trust Menninger when she trains them in communication skills. ‘I can talk their language, I know where they come from, and I know the kind of work that they do,’ she says. ‘I can help them challenge themselves to think about new ways of engaging our public.’

There are more intangible benefits as well. ‘I like the skills that [I’ve] gotten as a scientist,’ says Baker. ‘My ability to look at a problem and then break it down and think about each step, and how I can go through and try to address certain things, comes into my work all the time.’

The really excellent science communicators get the audience to care

Researchers hoping to enter the field must cultivate strong communication and empathy skills to connect with their audience. Bertley, who spent years as a bench scientist himself, says good science communicators need to respect their audience’s curiosity. ‘First of all, just stop being arrogant because you’re a scientist,’ he says. ‘There are no bad questions. So, when you’re speaking to somebody, especially if they don’t have any scientific training, or don’t have any science experience at a higher level, make sure you make them feel very comfortable [so] that they can ask you anything.’

Moreover, communicators have to go beyond facts and dive into storytelling to make an impact. ‘Most people get to where they’re pretty good at it, they get a pretty good definition for a complex term, they get a pretty good analogy for a complex idea, but then they stop there,’ says Frederick. ‘The really excellent science communicators go beyond that. They get to where what they’re saying is very clear and understood by their audience, and they get the audience to care about it.’

However, it’s no mean feat to get people to take an active interest in science. In fact, it can be quite emotionally draining. ‘Something that I really struggle with, and I fight so hard to work against, is people thinking that they can’t understand science,’ Behrmann says. ‘They tend to put themselves in the “Oh, I didn’t study science in college and never got science” box. Kids really young will put themselves in that box.’ Yet, she says, this is what provides her with a sense of purpose. ‘Making science as accessible as possible to the lowest common denominator, while explaining these really high-level and often invisible concepts, is part of the work that drives me the most.’

No comments yet