James Liao was one of the first to mix biology and engineering and he continues to break new ground in his quest for cleaner, greener biofuels, as Yfke Hager finds out

In 2006, James Liao found himself at a crossroads. Among the first generation of chemical engineers working in systems biology, he came to the realisation that his scientific pedigree offered exactly the right mix of technological knowledge and academic background to tackle the world’s fossil fuel crisis. ’I made a conscious decision to direct my research efforts towards solving the energy problem,’ he recalls.

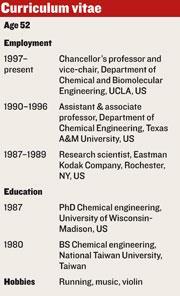

It was while working towards a PhD in chemical engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison that Liao first began to forge a career path characterised by the marriage of engineering and biology. He credits his advisor, Edwin Lightfoot, with inspiring a free-thinking philosophy. ’He was one of the pioneers who first recognised the importance of using engineering approaches to solve biological problems,’ says Liao. ’At the time - this was before the term synthetic biology had been coined - very few people were doing this, so it was an exciting period.’

Green genes

His innovative research did not go unnoticed, and Liao was fortunate enough to be offered a job a year before completing his PhD. Curious to see what industry had to offer, he accepted a position at Eastman Kodak. ’It was a natural extension of my PhD,’ he says. ’Kodak was one of the first large companies trying to commercialise synthetic biology.’ Here, Liao says, he began charting a course towards biologically oriented research. ’That was where I really started learning to manipulate genetics in order to modify microorganisms to make chemicals.’

It was always Liao’s intention to return to academia and in 1990 he began his academic career in earnest at Texas A&M University. Sharing a laboratory with microbial geneticist Ryland Young, Liao continued to explore the boundaries between scientific disciplines. ’In the early 1990’s, nobody was interested in using microorganisms to make biofuels, because oil was so cheap,’ he says. ’Scientists wanted to cure cancer, not create new fuels.’

A decade later, groundbreaking progress was being made in genomic sequencing, opening new avenues for research. In the meantime, Liao had moved to the University of California Los Angeles, US (UCLA), which proved to be fertile ground for interdisciplinary collaborations. ’I started working very closely with structural biologists,’ he says. David Eisenberg, director of the Institute for Genomics and Proteomics at UCLA, was ’extremely influential’ and solidified Liao’s interest in solving the energy problem.

Award-winning alcohols

Going green proved to be a good move. Last year, Liao received the Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Award from the US Environmental Protection Agency for developing biofuels derived from recycled carbon dioxide. It had all started when Liao decided to harness microorganisms to make higher alcohols. While higher alcohols make attractive biofuels, most microorganisms tend to produce only tiny amounts. But by genetically modifying Escherichia coli to express genes involved in the 2-keto acid pathway, which is instrumental in the synthesis of higher alcohols, Liao succeeded in developing a strain of E. coli that could produce far greater amounts of higher alcohols. ’In recent years we were able to expand on this technology, resulting in the development of microorganisms that can recycle carbon dioxide to make useful compounds, including biofuels,’ says Liao.

He continues to break new ground. Last year Liao co-founded EASEL Biotechnologies, a UCLA spin-off that will commercialise the carbon dioxide recycling process. It was a unique experience, he says, offering quite different challenges from academia. ’I wanted the technology I developed to have a real impact on the world, not just be published in academic papers.’

But Liao is painfully aware that the energy problem is a long-term endeavour, noting that the problem is ’so big that no single lab can come close to solving it.’ As his quest for cleaner and greener energy continues, he lists the considerable challenges ahead. ’Funding for the energy research budget is only 1 per cent of the healthcare research budget,’ he points out. ’The field is now at the same stage that cancer research was at a few decades ago; we’re still figuring out how to formulate the problems. We need to find a way to produce biofuels efficiently enough to compete with petroleum - and that’s not an easy task.’

Yfke Hager is a freelance writer based in Manchester, UK

No comments yet