The challenges of learning chemistry in your non-native language

Let’s face it: there is an expectation of us all in the world of chemistry to know what we are talking about. Not only do we have to discuss specifics with colleagues in our chosen field, but we also face a public questioning what we’ve developed, why and what benefits were gained.

In my case: I designed and made interlocked molecules resembling a ring on dumbbell, called rotaxanes; I improved their production to select one or two rings on the dumbbell for future applications; and gained the valuable knowledge that certain molecular structures should not be demonstrated with impromptu hand gestures during presentations.

Of course, hand gestures do not necessarily mean you are speechless (even if your audience may briefly be). Once we routinely apply skills, it’s easy to forget that we once had to be taught them with their terminology.

So, what of students learning in a second or even a third language? As a teacher, any temptation to oversimplify from the outset must be resisted (this is Verschlimmbessern in German: making things worse out of a desire to improve them). Yet as a student under pressure, escaping questioning through nodding and smiling can appeal. So how does a teacher tell if the student truly grasped the point or was simply evading attention?

While doing an advanced language course to take up a job abroad, I took an open unit in chemistry in Japanese. I would argue that even if the student may not yet communicate it effectively in your language yet, they know more than you might think.

Early indicators

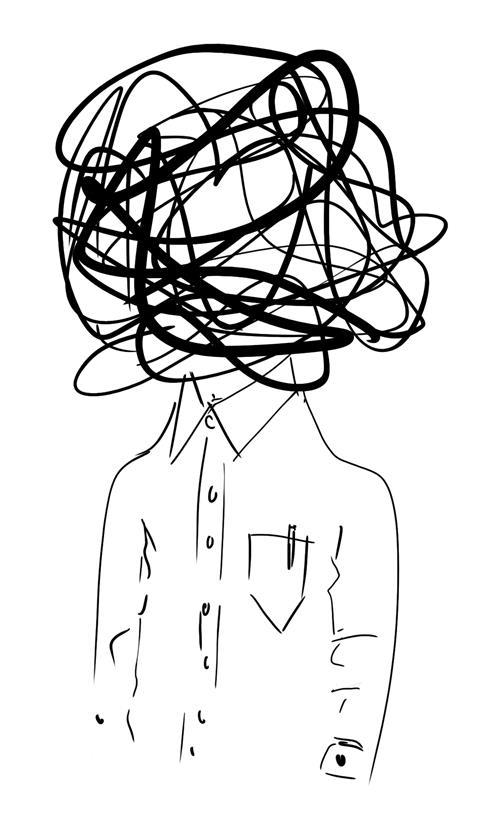

Make no mistake, your first lecture in a second language is a pin-drop into the deep end. Even if the figures and schemes seem familiar, words that are not stick distractingly in your mind. Now that I use these terms routinely, remembering these initial confusions intensifies the recall. However, had the introduction been a sudden drop mid-conversation, instead of being presented in such a clear context, would I have stood a chance?

Even if a student may know a concept, the demonstrations and experiments may be as different to those in your class as the language. Familiarity is a scale: qualitative test tube reactions are simple even with an unfamiliar chemical system; titrations have a familiarity that may perhaps breed contempt; whereas in my case, making ice cream by rapid cooling and making elastomer ‘slime’ were experiments I once taught myself.

That said, a simple demonstration of adiabatic pressure changes using a PET drinks bottle of water with a dropping pipette inside, resembling a Galileo thermometer, was new to me. Squeeze the bottle and the pipette draws water and sinks, refloating upon release. A simple, inexpensive and elegant way of making the key density differences easy to understand and variable.

A question of control

Students may not realise that their groupmates are not just friends but control variables, both when checking their own understanding in class and as mark comparators when monitoring progress. Add language and cultural differences to the mix and the importance of this grows.

Imagine how my lab partner must have felt, not only being left with the only foreign student but a man nearly twice her age, in a class where mixed pairs were unusual. Were it to have been me, I am not sure I could describe that feeling in my own language (the Japanese iwakan comes close).

If it sounds like a comedy film premise, then my repeated failures to make honeycomb would probably add to that, even if I could only recall the English name after the class. (The French term for this phenomenon, l’esprit de l’escalier, has largely replaced the English afterwit.)

Thankfully, we worked together well. She saved me from language misunderstandings and doing too many titration repeats, whereas I managed some scientific explanations and a few extra control experiments to get useful electrochemical data points.

Conclusive results

After the practical comes the challenge of putting your results into writing. You may have done research, but can you translate it? In a way, previous experience in your own language is paradoxically a barrier to attainment in class: fine detail in your first language is hard to summarise in a second. Even in English, formal written language differs from conversational language, as much as the distinction is stricter in some other languages. Despite this, my labmate and I both got excellent marks, the comedy writers likely sensing sufficient embarrassment in class to graciously spare me a final humiliation.

So, what of the teacher in me, looking back now? I’ve learned that concepts need to be communicated clearly and effectively to students, wherever they come from, but English is neither perfect nor universal. Bidirectional verbal communication remains essential. But in facial expressions, eye movements and hand gestures, your students show that they know more than they can say.

No comments yet