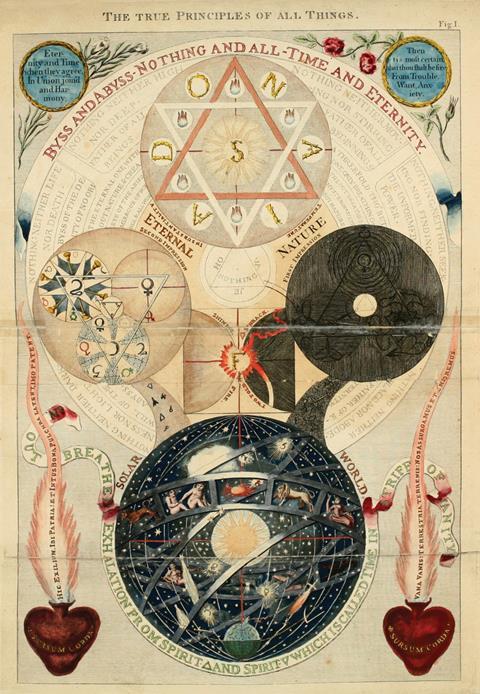

In this excerpt, Philip Ball explores how the modern chemist emerged from alchemists’ early efforts to order and systematise the world

An extract from Alchemy

This chapter is reproduced from the book Alchemy: An Illustrated History of Elixirs, Experiments, and the Birth of Modern Science by Philip Ball.

The book is available to purchase from Yale University Press.

In popular legend, Robert Boyle is the ‘man who killed alchemy’.

The Belgian–American chemist and historian George Sarton, sometimes considered one of the founders of the modern discipline of the history of science, called Boyle ‘one of the best prototypes of the modern man of science,’ in contrast to alchemists, who were ‘fools or knaves’ (or both). The American historian of magic and early science Lynn Thorndike denied, despite abundant evidence to the contrary, that Boyle had any interest in gold-making or even believed it possible. The goal of many such ‘histories’ was to find a path linking Boyle to the pioneering chemists of the late 18th century: historian Marie Boas Hall claimed in the 1960s that Boyle was ‘preparing the way’ for French chemist Antoine Lavoisier’s reassuringly modern ideas while getting rid of the mystical trash of alchemy.

It’s now clear that such narratives – examples of what today’s historians call Whig history, which prunes and interprets the past to create a sense of inexorable progress towards modernity – are fictions. Boyle was very much interested in alchemy and eagerly sought the philosopher’s stone that could transmute metals into gold.

Central to the old view of Boyle is his 1661 book The Sceptical Chymist, which Boas Hall called a ‘withering blast’ against alchemy. Here Boyle is credited with introducing the modern concept of a chemical element. Neither of those claims stands up to scrutiny.

In defining an element as a substance that can’t be broken down into simpler ones, Boyle wasn’t really saying anything new or controversial – and besides, he seems to doubt whether any such substances truly exist. And like many of his contemporaries, Boyle was not trying to discredit alchemy but rather to separate what is good and useful in it from what is vague or dishonest.

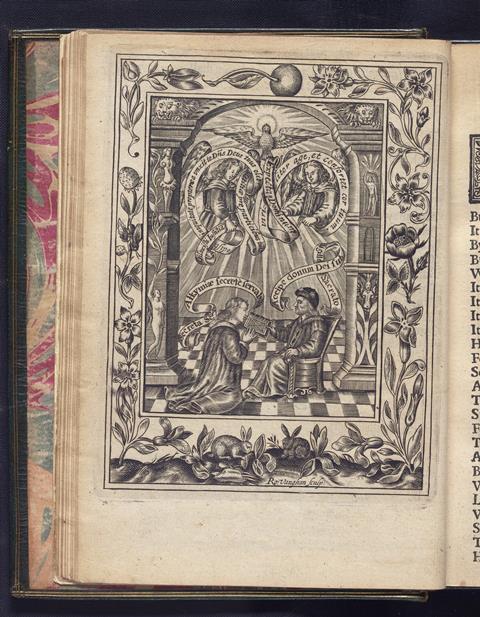

He endorsed an old distinction between true adepts who know the secret of chrysopoeia (making gold) and vulgar cheats or untutored laborers such as dyers and distillers who don’t understand what they do (Boyle puts himself in the former category, naturally). The Sceptical Chymist was no death knell for alchemy but a call (and not the first) for it to clean up its act.

Boyle was himself not always skeptical enough. He was seemingly taken in by a French conman named Georges Pierre des Clozets who claimed to know the secret of the philosopher’s stone, lavishing him with gifts in the hope that he would reveal all. Boyle even wrote a manuscript called ‘Dialogue on Transmutation’ (which was never published, and of which only fragments survive) in which he considered the possibility of chrysopoeia.

Although in the late 17th century there was plenty of skepticism about transmutation, it was by no means embarrassing or disreputable to have an interest in the subject. Yet while Boyle published some of his studies openly in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, both he and his colleague Isaac Newton often observed the old alchemical tradition of secrecy, seemingly believing that such powerful knowledge should be kept within a circle of elite adepts. They were not ‘modern,’ but their alchemical interests did not make them backward-looking either. Like most great thinkers, they were simply of their time.

Part of the appeal of the Boyle myth may be that it promised a clean break: a waymark at which alchemy was cast aside and chemistry took over. But such changes rarely if ever happen in science, and the transition of alchemy to chemistry – often denoted as having happened via the intermediate discipline of chymistry – was certainly not like that.

Alchemy was transformed to chemistry in the manner of all alchemical transmutations: through a process of separation, distillation, and purification. This transformation was already underway in the 16th century, particularly in the reception of the works of Paracelsus. Some Paracelsians, such as Michael Sendivogius, pursued the alchemical quest at full throttle. Sendivogius worked for a time in the court of Rudolf II, and on a diplomatic mission in Poland he was said to have demonstrated a successful ‘projection’ of base metals into gold, witnessed by the Polish king. A copy of Sendivogius’s 1614 book Novum lumen chymicum (translated as A New Light of Alchymie) was much thumbed in Newton’s library.

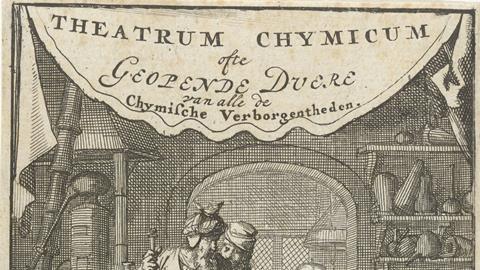

Others, such as Andreas Libavius, while sharing the Paracelsians’ enthusiasm for chemical medicine and their rejection of the old dogmas of Galen and Aristotle, wanted to strip chymistry of mysticism, speculation, and theology and make it a robustly practical art. Such a down-to-earth approach to chemistry was reflected in Hieronymus Brunschwig’s books on distillation and in the treatises on metallurgy and mining De la pirotechnia (On pyrotechnics; 1540) by Vannoccio Biringuccio and De re metallica (On the nature of metals; 1556) by Georgius Agricola. There were no appeals to divine inspiration or magical forces here—and as to claims of transmutation, Agricola remarks, ‘I should say the matter is dubious.’ Some alchemists, he says, simply deceive others (or themselves) with fraudulent schemes.

By the start of the 17th century, chymistry was deemed to warrant a place in the academic curriculum. In 1609 the German Paracelsian Johannes Hartmann was appointed professor of chemistry (actually ‘chymiatria’) at the University of Marburg – some say this was the first such post in the world, although there is evidence that university instruction in aspects of chymistry goes back further. Over the course of that century, the textbooks by Jean Béguin, Nicaise Lefebvre, and Nicolas Lemery marked the emergence of chemistry as a respected and practically oriented discipline.

The chymical chimera

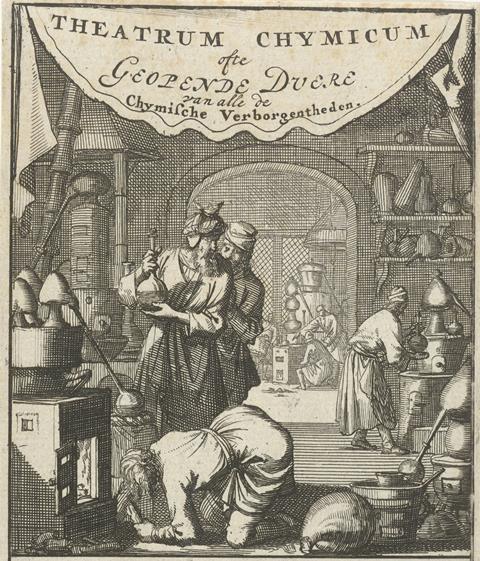

This professionalisation of chymistry went hand in hand with efforts to make it a useful discipline, to make the materials that society needed, such as medicines, metals, oils, dyes, and pigments. We saw earlier how Libavius and the German chymist Johann Joachim Becher called for the establishment of formal chemical laboratories – something between research institutes and factories – both as places of manufacture and to systematically discover new processes.

As well as being a decidedly practical (if ultimately unsuccessful) alchemist, Becher put forward a new theory of the constitution of matter. He acknowledged only two classical elements: water and earth. But he asserted that there are in fact three distinct earths, which we can recognise as the Paracelsian tria prima of sulfur, mercury, and salt under new names. Terra fluida (or mercurialis) was the principle of fluidity, based on mercury; terra lapida or ‘vitreous earth’ represented solidity, derived from salt; and terra pinguis, ’fatty earth,’ basically fiery sulfur, made matter oily and combustible.

Becher laid out this scheme in his 1669 book Physica subterranea (Underground physics). In a new edition of the book published and edited by the chemist and physician Georg Ernst Stahl, chair of medicine at the University of Halle, Stahl gave terra pinguis a new name: phlogiston, derived from the Greek phlogistos, ‘burning’.

In phlogiston, the rather vague and immaterial notion of a ‘principle’ of fire and combustion was elevated into a physical substance – one that, for the rest of the century, chemists sought to isolate and measure. The phlogiston hypothesis could seemingly make sense of, and indeed unify, a range of chemical processes.

Stahl asserted that when a material such as wood burns, it releases phlogiston into the air. It was known that such substances, if ignited and placed in a sealed vessel, would cease burning after a short time: Stahl’s theory explained this on the basis that the air in the container becomes ‘saturated’ with phlogiston and can accept no more. Meanwhile, the reason nothing will burn in a vacuum, as Boyle had shown in his experiments with a vacuum pump in the 1650s, was because there was no air to take up the phlogiston. Metals, when heated in air, lose their phlogiston and transform to a dull residue called a calx. Charcoal can release metals such as iron from their ores because it is rich in phlogiston and so will add this substance to the ore (which is like a calx) to restore the metal.

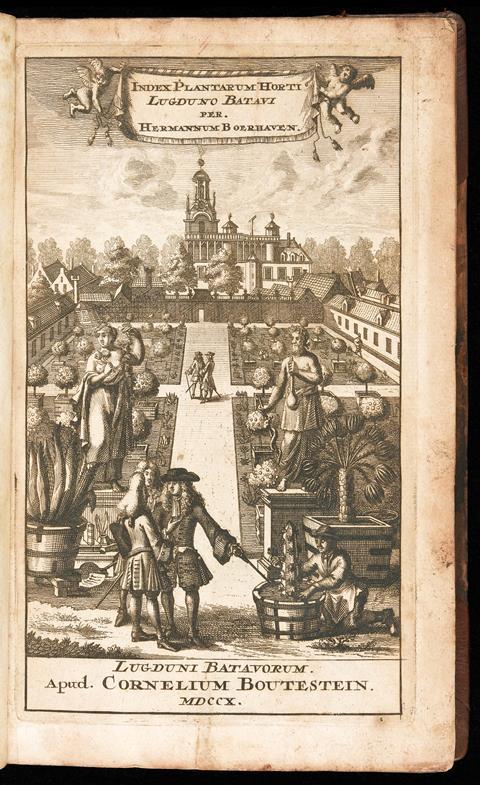

While phlogiston was not universally accepted by 18th-century chymists, few questioned its central premise that fire and combustion relied on some flammable substance. The influential Dutch scientist Hermann Boerhaave, professor of botany, medicine, and chemistry at the University of Leiden, made no mention of phlogiston, but put in its place a combustible ingredient called the pabulum ignis, a ‘matter feeding fire’. Boerhaave’s 1732 Elementa chemiae (Elements of chemistry; he maintained the increasingly outmoded practice of writing and lecturing in Latin) is perhaps the closest thing to a foundational textbook of a modern form of chemistry, establishing the idea that different chemical substances unite according to their affinity – which Boerhaave called a kind of ‘love’ – for one another. He had little patience for the speculative excesses of alchemists, writing, ‘How I wish … these raving men had restrained themselves and not wished to interpret the Sacred Scriptures in terms of chymical principles and elements.’

The phlogiston theory is often derided now as a flawed idea that held chemistry back for the best part of a century. That is a Whiggish view: if only we hadn’t persisted with a wrong idea, we could have found the right one! In fact, phlogiston, much like chrysopoeia, was precisely the kind of concept that scientists have always needed to enable them to keep going when their understanding is scanty. Phlogiston allowed chemists (we can call them that by the mid-18th century) to think about processes such as the smelting and corrosion of metals and the burning of fuel using the same framework with which they pondered respiration. Phlogiston theory was wrong – there is no such substance – but it was so nearly right as to be fruitful. Things burn not because they release some combustible substance into the air, but because they take something from the air: the gas that Antoine Lavoisier christened oxygen in the 1780s. Metals do not lose anything when they form a calx; rather, they have combined with oxygen.

Stimulated by phlogiston theory, 18th-century chemistry became the study of ‘airs’ – or gases, a word coined by Jan van Helmont. So long as air itself was regarded as an indivisible element, it remained hard to make sense of all the different kinds of airs that chemists identified: fixed air, mephitic air, inflammable air (the latter, identified by the Swedish chemist Wilhelm Scheele, was suspected by some of being pure phlogiston). We now recognise these as different gases: carbon dioxide, nitrogen, hydrogen. It was Lavoisier’s oxygen theory, in which ordinary air was understood as a mixture of oxygen and nitrogen (which Lavoisier called azote, as French chemists still do), that finally made sense of it all – to the chagrin of staunch advocates of phlogiston, as some remained even into the early 19th century.

Lavoisier also clarified the idea of a chemical element – not by defining it (he more or less kept Boyle’s definition of a substance that couldn’t be separated into simpler ones) but by drawing up a list of them in his seminal 1789 textbook Traité élémentaire de chimie (Elementary treatise on chemistry), which helped to secure his oxygen theory within France. He listed 33 elements – the roster grew ever longer through the 19th century – including all the known metals. If these elements were indeed fundamental and irreducible, most scientists decided that there was no longer any point in attempting transmutation.

The last of the alchemists

But not all scientists agreed. Alchemy’s Great Work might have been generally discarded and mocked by the late 18th century, but it was not abandoned entirely.

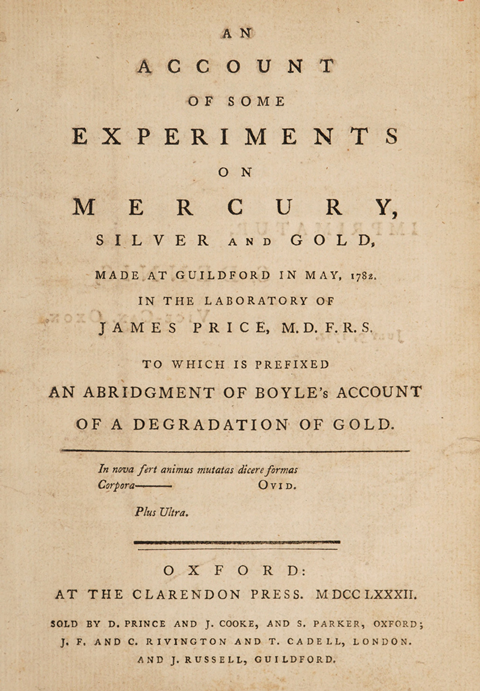

One of the late would-be alchemists was English chemist James Price, who in 1782 claimed to have transmuted mercury into silver and gold. He demonstrated his results at his home near Guildford in Surrey to a distinguished audience that included several lords. Despite skepticism from others, Price was awarded an honorary degree from the University of Oxford for his ‘chemical labours’.

Price was no fringe figure but a Fellow of the Royal Society – which made his claims all the more outrageous to many of his peers. Faced with demands that Price be expelled from the ranks, the president of the Royal Society Joseph Banks demanded that the chemist – whom Banks sardonically dubbed ‘our Paracelsus of Guildford’ – demonstrate his experiments before them. Eventually, Price agreed to perform a transmutation for other Fellows invited to his home – but on the day of that event, he committed suicide by drinking poison. (Some say he dropped dead in front of his audience.)

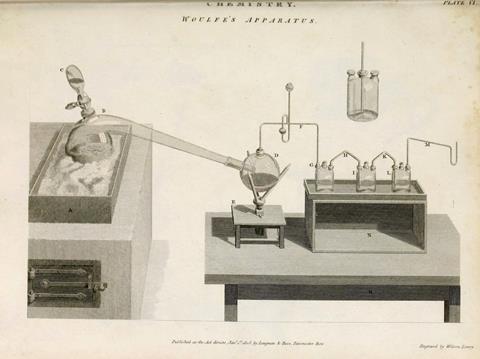

According to John Timbs, author of English Eccentrics and Eccentricities (1866), ‘the last true believer in alchemy was not Dr Price, but Peter Woulfe, the eminent chemist, and Fellow of the Royal Society, who made experiments to show the nature of mosaic gold [tin sulfide, an old form of ‘artificial gold’]’. Woulfe was an Irishman who lived in London in the late 18th century, and his chemical prowess brought him impressive accolades: he was given the Royal Society’s Copley Medal in 1768, its oldest and most prestigious award, and delivered the society’s Bakerian lectures for three years in a row in the 1770s. Older chemists today might know him as the inventor of the triple-necked Woulfe bottle for collecting gases. Yet, to the dismay of his colleagues, in later life he became fixated on the transmutation of metals. The 19th-century English chemist William Brande reported that Woulfe’s rooms in Holborn, London, ‘were so filled with furnaces and apparatus that it was difficult to reach his fireside … He had long vainly searched for the Elixir, and attributed his repeated failures to the want of due preparation’.

Woulfe’s pursuit of alchemy probably arose from his involvement in esoteric movements such as Rosicrucianism, Freemasonry, and the heterodox religious movement begun by the theologian and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg (whom he met in 1769). So thoroughly discredited was alchemy by this stage that Woulfe was thought by his peers to have lost his mind, perhaps because of his isolation or because of chemical poisoning from his earlier career. The eminent French chemist Antoine François de Fourcroy, a colleague of Lavoisier, wrote in 1799 that ‘The famous Woulfe is in a state of mind which must cause much sorrow to friends of philosophy and science … [He] is no longer interested in chemistry; in his experiments he could no longer use any iron that would not suddenly turn into copper or lead.’

Transmutation at last

Despite such ridicule of would-be modern chrysopoeians, the 19th-century French chemist Marcellin Berthelot rehabilitated alchemy’s image by claiming that a great deal of useful chemistry was discovered in the futile quest to transform metals to gold.

The German chemist Justus von Liebig offered a more generous (one might say too generous) assessment than did many later historians of chemistry when in the 1850s he wrote that ‘Alchemy was never at any time different from chemistry. It is utterly unjust to confound it, as is generally done, with the gold-making of the 16th and 17th centuries … Alchemy was a science and included all those processes in which chemistry was technically applied.’

All the same, it was generally agreed by this time that transmutation of the elements was a futile enterprise. And yet … were we so sure of that? After all, the idea that there might be some fundamental matter, like the Aristotelian protē hylē, from which all substances are made, was still alive and well. After the English chemist John Dalton expounded in the 1800s his theory that all substances are composed of atoms, chemists began to measure the relative weights of the different elements and discovered that these seemed to be whole-number multiples of the weight of the lightest, hydrogen. In 1815 the chemist William Prout proposed that the atoms of all elements are indeed compounded from hydrogen atoms squeezed together.

This is sort of true. The New Zealand–born scientist Ernest Rutherford showed in the early twentieth century that atoms are not after all the unsplittable (Greek a-tomos) objects long supposed but are made of yet more fundamental particles: a dense nucleus containing subatomic particles called protons (and, as was later discovered, neutrons too), surrounded by a cloud of much lighter electrons. Hydrogen atoms, which have only a single proton in their nucleus, are thus in a sense the constituents of all others. Indeed, we now know that all other elements are made by the fusion of hydrogen nuclei, a process that happens continually in the interiors of stars and generates their tremendous output of energy. Rutherford and others deduced that heavy atoms can be split apart by nuclear fission reactions – the process that releases heat in nuclear reactors and in the first atomic bombs. In both fusion and fission, one element is turned into another. By bombarding atoms with high-energy beams of fundamental particles in particle accelerators, other elements have indeed now been transformed into gold.

When Rutherford and his collaborator, the English chemist Frederick Soddy, first discovered the transmutation of elements by nuclear fission in 1901, he was alarmed at how it might look to their colleagues. Forced to the conclusion that the radioactive decay of the heavy element thorium transformed it into a different element (now recognised as radon), Soddy is said to have exclaimed ‘Rutherford, this is transmutation’ – whereupon Rutherford shot back ‘For Mike’s sake, Soddy, don’t call it transmutation. They’ll have our heads off as alchemists.’ For what could be more heretical in modern science than that?

No comments yet