Promising clinical trail for poison-derived cancer treatment

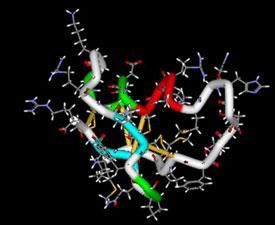

Scorpion venom carries a nasty sting for brain tumour cells, according to US researchers. A peptide based on chlorotoxin, found in the venom of the Giant Yellow Israeli Scorpion, has been used to target glioma, a particularly aggressive form of brain tumour.

A synthetic form of the peptide, known as TM-601, is not only able to pass the blood-brain barrier with ease, but also seeks out and selectively binds to glioma cells.

Adam Mamelak of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, leads that group who synthesised TM-601 and bound it to the radioactive isotope iodine-131 (131I). The tumour-targeting ability of the radioactive peptide complex means that it can deliver a highly-localised dose of radiation directly to gliomas without harming other tissue.

The therapy has now successfully completed phase I trials to test whether patients can tolerate the drug, the team report in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.1 The drug is already in phase II trails and showing early promise, according to results presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting in Atlanta, Georgia, on 4 June.

Fast and deadly

Gliomas are extremely deadly, fast-growing tumours which account for around half of all brain cancers. Surgery to remove gliomas inevitably leaves behind small amounts of cancer cells which quickly proliferate, meaning patients also have to undergo dangerous radiation and chemotherapy.

In the trial of TM-601, 18 patients had a small catheter inserted into the cavity that was left behind after their brain tumours had been removed surgically. Two weeks later the patients received a dose of the 131I-TM-601 complex through the catheter directly into the cavity. The dose was well tolerated by the patients, with very few adverse side effects, the scientists say. Intriguingly, magnetic resonance imaging showed that in two patients the tumours had disappeared completely following the treatment.

’[The drug] is small, has highly specific binding, and is not toxic to normal cells. These factors alone make it a highly desirable agent.’ said Mamelak. ’From lab experiments we know that it binds melanoma, lymphoma, lung cancer, and a wide variety of other tumours, so we are hopeful the drug will find much wider application.’ he explains. The team are working with biotechnology company TransMolecular of Cambridge, Massachusetts, to further develop the drug.

Ed Yong, cancer information officer at Cancer Research UK, told Chemistry World: ’Treating brain cancers with radioactive scorpion venom sounds like science fiction. But this preliminary study shows that this approach is safe and has potential. Now, larger trials are needed to work out how effective it is.’

Tom Westgate

References

A Mamelak et al.,Journal of Clinical Oncology, 24, 3644

No comments yet