The extent of fraudulent papers in the scientific literature is growing exponentially and goes far beyond isolated events, new research has revealed. ‘You can see a scenario in a decade or less where you could have more than half of [studies being published] each year being fraudulent,’ says Reese Richardson, one of the study’s key researchers at Northwestern University, US.

Scientific integrity and honesty are key pillars of science and research, yet in recent years large organisations – known as paper mills – have been threatening these ideals by facilitating systemic scientific fraud.

Each year, paper mills produce and sell thousands of often poor-quality or fake scientific studies, sometimes using entirely made-up or doctored data and images. Growing pressure for researchers to ‘publish or perish’ has contributed to an increasingly competitive scientific community, leading some to turn to these businesses to pad their publication record. ‘It becomes sort of a snowball situation where the optimum strategy is you have to start to cheat in order to win out,’ says Richardson.

Widespread problem

Previous studies have exposed paper mills using specific cases, rather than looking at the issue systematically. To gain a sense of the scale of the problem, the team, led by Luís Nunes Amaral, analysed a collection of paper-milled manuscripts discovered by science sleuths and found that the problem is even worse and more widespread than thought. ‘There are networks of individuals and entities that are producing scientific fraud at scale,’ says Amaral.

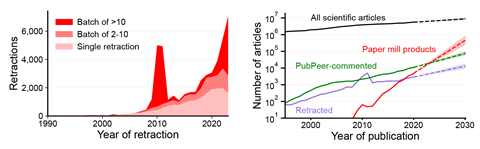

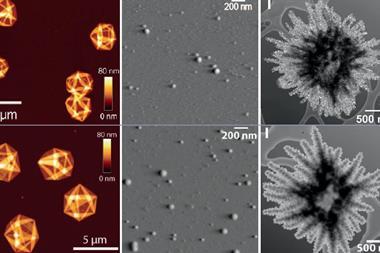

Analysis of 2213 articles flagged for image duplication – a hallmark of fraudulent science – revealed that such articles are published in large batches. The researchers also suggest that paper mills cooperate with brokers, a small number of dishonest editors who control some of the publishing decisions at select journals. Even a small number of brokers can lead to the publication of huge numbers of counterfeit articles, with publisher Frontiers recently announcing that they are retracting a batch of 122 articles.

Despite efforts to curb paper mills, Amaral and his team found that suspected paper-milled articles are growing exponentially, doubling every 1.5 years. In comparison, the total number of all publications is only doubling every 15 years.

‘I’m not sure that [the researchers] are being clear enough why this is happening. It’s about money and the need for publications. [But] in scientific research those shouldn’t be the key factors,’ says Jana Christopher, an expert in image integrity who works for the publisher FEBS Press.

The team’s analysis of articles published by Plos One – a peer-reviewed open-access mega-journal that discloses the handling editor – identified 45 editors who accepted articles that were more likely to be retracted or receive post-publication comments on PubPeer than chance would predict. These individuals comprised just 0.25% of the journal’s editors, handling 1.3% of Plos One articles published in 2024, yet they oversaw 30.2% of the journal’s retracted articles.

Network analysis revealed that these editors send most of their submissions to one another over other editors. The team found the same trend when analysing data from 10 Hindawi journals – another open-access publisher – and the Institute of Electronics and Electrical Engineers’ (IEEE) conference proceedings.

These paper mills continue to churn out fraudulent papers and few fraudsters are ever caught and shut down. As a result, the scientific community has become increasingly concerned by paper mills, leading to efforts to curb their influence. Consequently, paper mills must now adapt to guarantee publication for their clients, ‘hopping’ between journals as they become de-indexed or fall out of favour with customers.

Amaral and his team found evidence of a fraudulent publishing service – known as the Academic Research and Development Association (ARDA) – that demonstrates this behaviour. The researchers found that the list of the association’s journals evolves to continue guaranteed publication for customers, with it changing in direct response to de-indexing by academic databases such as Scopus or Web of Science. While this is just one case, the team notes that the rapid rise in the number of papers some journals publish is consistent with ‘hopping’, highlighting that this is a widespread practice.

Fraudulent scientific activity is not consistent within each scientific field, with the researchers highlighting that fraudsters preferentially select certain sub-fields over others. The team found that within six sub-fields of RNA biology the retraction rate – a sign of the number of fraudulent articles – was inconsistent. ‘Some subfields of RNA [biology] are now so polluted by fraudulent research that it essentially becomes impossible for legitimate researchers to even enter the field,’ says Amaral.

Moving forward

The solution to this issue remains divisive. Current strategies involve using artificial intelligence and tools to identify non-standard phrases and duplicate or doctored images, post-publication peer review and retracting fraudulent articles after publication. Christopher notes that ‘it’s going to be increasingly difficult to distinguish between genuine research and low quality or made up content’, especially as the number of fraudulent articles increases.

Amaral believes that the situation needs collective action from institutions, such as the learned societies and national academies. ‘You cannot have a system where you are trying to detect fraud after it’s created. You actually have to prevent people from putting these things into the system,’ he says.

He adds that restricting researchers engaging with paper mills and fraudulent papers would be beneficial and create a fairer scientific community. However, Richardson believes that penalising the clients of paper mills is not the answer and calls for systemic change. ‘We need to make the scientific [community] much less competitive, fairer and more equal. Inequality, locally and globally, has led to this problem,’ he says.

References

R Richardson et al, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 2025, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2420092122

No comments yet