Adding low-cost gelling agents to anti-icing fluids could keep grounded aircraft ice-free for longer. The new anti-icing fluids, developed by researchers in the UK, form supramolecular polymers that can prevent ice forming on aircraft wings for over twice as long as current products.

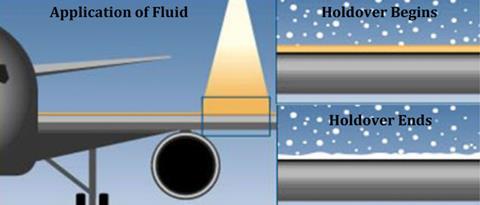

During cold weather, ground crew often spray aeroplane wings with film-forming anti-icing fluids to increase ‘holdover time’ – the period in which surface ice doesn’t form. Force applied by the air during takeoff then removes the protective layer.

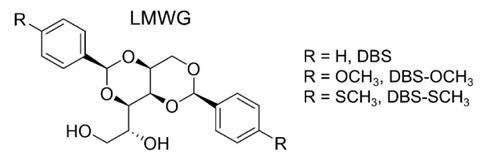

Researchers the University of York, along with collaborators at the anti-icing specialist Kilfrost, have now developed gel materials with enhanced anti-icing properties. The team added derivatives of a gelling agent called 1,3:2,4-dibenzylidene sorbitol (DBS) to existing anti-icing fluids made from a 50:50 mixture of water and propylene glycol and some other additives. DBS is made by reacting the sugar sorbitol with benzaldehyde, both of which are low-cost and can be derived from non-oil sources, explains York chemist David Smith, who led the project.

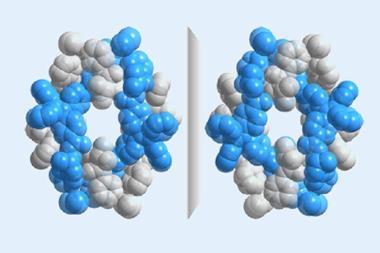

Upon mixing, a combination of π–π stacking interactions and intermolecular hydrogen bonds leads the DBS molecules to self-assemble into a supramolecular gel. The team tested the efficiencies of various gel formulations by applying them to aluminium plates that are used to model aircraft wings and spraying these with water in ice-cold conditions. ‘A fairly standard anti-icing fluid gives you a holdover protection of about 30 to 40 minutes,’ says Smith, who adds that an anti-icing fluid containing just 0.25 grams of gelling agent per litre had an increased holdover time of over 90 minutes.

Smith explains that the gels will break down easily during takeoff because they’re held together by non-covalent interactions, unlike the more robust cross-linked polymer networks formed with current anti-icing sprays. He adds that the runoff from the gels could be collected along the runway and later repurposed.

Jonathan Steed at Durham University in the UK explains how this work shows that ‘a clear dialogue between academia and industry can give rise to a really novel solution to a real-world problem’. ‘Smith and his team have really thought through how the materials might work in practice,’ he adds.

References

N K McLeod et al, Langmuir, 2025, DOI: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5c05067

No comments yet