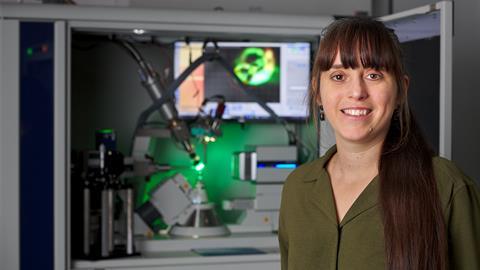

Lauren Hatcher discusses her work developing techniques for time-resolved crystallography

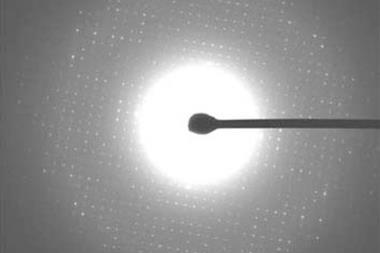

Lauren Hatcher’s work is all about making movies of crystals. Using in-situ x-ray diffraction methods, her team seeks to understand how dynamic changes at the molecular level affect macroscopic properties. ‘If you better understand what’s happening, you can try and harness it to your advantage,’ she says – and her work is helping to do just that.

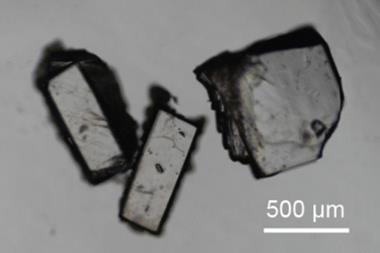

Like many crystallographers, Hatcher enjoys puzzling over data to put together the 3D structure of crystalline materials. A year spent working at GlaxoSmithKline as part of her undergraduate degree, learning various crystallisation techniques, furthered her interest, before she continued in the field of crystallography for her PhD. ‘You grow these beautiful crystals, and they sparkle like jewels,’ she says. ‘But it always amazes me how you can get so much information from something so tiny.’

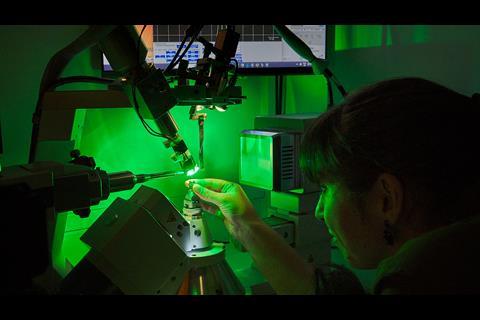

Today, Hatcher’s work primarily focuses on studying small, photoactive molecules, such as photoswitches, which change between isomers when exposed to light. The team has developed new methods in time-resolved and serial crystallography, to study changes in the crystal structure of such molecules in real time. ‘We try to follow chemical reactions within the crystal so that you can get a 3D picture of what’s happening at very short timescales,’ says Hatcher. ‘For example, if a material is photochromic, you want to know what it is about the structure that’s causing the colour change.’

To do this, a light source excites the molecules within the crystal, before a diffractometer probes the structure with x-rays. Simple LEDs fitted into the diffractometer can provide long pulses of light, while extremely short pulses are only possible using ultrafast lasers. To meet the x-ray source requirements, the team primarily visit synchrotron facilities, such as Diamond Light Source in the UK. Hatcher notes that the strength of the x-ray pulses at these facilities is ever increasing, which can cause incremental crystal damage or even destroy the crystal entirely.

It always amazes me how you can get so much information from something so tiny

‘Macromolecular crystallographers are usually ahead of the game with these issues as their crystals are typically trickier to handle,’ says Hatcher. ‘Where damage to the crystal happens too quickly to build up an overall 3D structure, these scientists have to collect data on multiple crystals using techniques such as serial crystallography.’

A series of snapshots

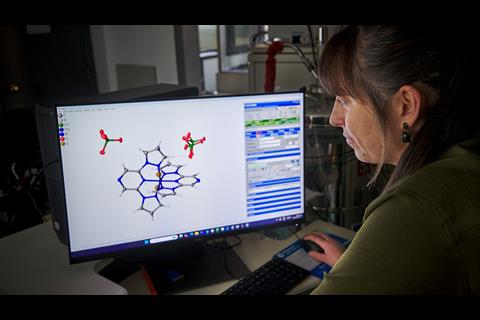

Hatcher’s team uses similar practices to study its own small-molecule crystals. Rather than standard single crystal x-ray experiments, the team mounts a grid of 20 by 20 wells – each containing a small volume of microcrystals – onto a diffractometer. ‘You then hit each crystal shot by shot, moving to a different crystal for each data image. Combining the images from many crystals allows you to generate the complete dataset,’ explains Hatcher. For time-resolved studies, taking repeated measurements at different time points generates a series of 3D snapshots, which can be stitched together, like frames in a movie.

‘It’s very easy to forget that every measurement you make is an average over the time it takes to do the experiment, and a statistical average over the number of photoactive molecules within the crystal that you’re illuminating,’ explains Hatcher. She adds that seeing changes of individual molecules in response to light is not possible with this experimental set-up, but how the combination of these changes affects the overall 3D structure and population dynamics across the crystal is. Combining this experiment with spectroscopic and computational data would provide a more holistic overview of what’s happening.

‘We’ve got a bespoke instrument that we’ve developed in our lab that can probe as quickly as milliseconds,’ says Hatcher. ‘But we also do a lot of work at Diamond Light Source in the UK to work at the sub-microsecond timescale.’

The team is expanding the use of this technique to other materials, including light-responsive materials used for solar energy applications, as well as pyroelectric materials which convert heat into electrical energy. Studying in-situ changes of crystals in response to high pressure or exposure to gas may also be possible, but Hatcher notes that such experiments are currently not common and would require collaboration with other researchers. ‘There are also lots of opportunities for streamlining with the help of machine learning, not only of data processing, but actually the way that you collect data,’ says Hatcher.

This year, Hatcher received the George Sheldrick Prize from the European Crystallographic Association for her pioneering contributions to time-resolved crystallography. She was also awarded a Harrison-Meldola early career prize by the Royal Society of Chemistry for her innovative work with real-time photocrystallography. ‘I think these awards are really reflective of the collaborative effort required to succeed with these experiments, not only by my students and postdoc, but also the teams at the synchrotron facilities,’ says Hatcher. ‘Sometimes there’s very late nights or shift work when you’re awarded a certain amount of time to use specialist equipment.’

The team is now working with x-ray free-electron laser facilities in Europe to conduct experiments with pulses of light as quick as femtoseconds, to hopefully visualise the initial stages of certain photochemical reactions.

References

S Lewis et al, Comms. Chem, 2024, 7, 264 (DOI: 10.1038/s42004-024-01360-7)

No comments yet