Briony Marshall

Pangolin London, King’s Place, 90 York Way, London

Until 15 June 2013

I will never forget the infectious enthusiasm of Zafra Lerman, one of the best chemistry teachers in the world, as she described teaching children about atomic unions in molecules by making them hold hands and dance. The ‘molecular dance floor’ is a popular pedagogical image, but the experience of doing the dancing makes those ball-and-stick diagrams literally come alive for children.

Lerman’s approach inspired me to represent the structures of water and ice as gnome-like molecules grasping one another’s ankles in fourfold tetrahedral coordination, when the editor of my book H2O: a biography of water outlawed the balls and sticks I’d originally offered. That’s one reason why I was thrilled to discover that British sculptor Briony Marshall had created such a three-dimensional lattice of tetrahedral figurines out of bronze. Her sculpture doesn’t depict hydrogen-bonded ice, however, but the equivalent covalent crystalline lattice of diamond in a work called A dream of a society as flawless as diamond. Over the next month, you can see it for yourself at the Pangolin Gallery in London.

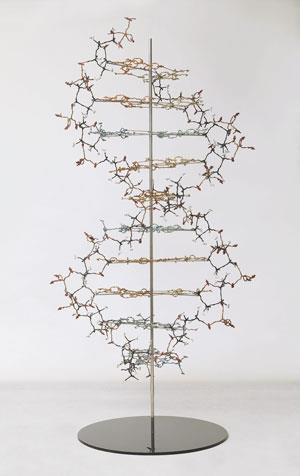

Marshall’s exhibition, Life forming, features various chemistry-inspired sculptures, including, most beautifully, a network of atomic figurines in the double-helical dance of DNA. Each element of this piece is realised with as much fidelity to chemical truth as possible. Carbonyl double bonds are two-handed unions; hydrogens are peripheral, fetal figures held with a lone parental grip. And how about five-valent phosphorus? Long hair has its uses. In scale and form this sculpture recalls the famous Watson–Crick model in that iconic photograph (60 years old this year) – but however familiar the structure has become in the meantime, no other representation succeeds quite so well in linking the Platonic elegance to the molecule’s central role in life. Almost as striking as the piece itself is its shadow, cast on the plinth, where the helix dissolves into a web of humanoid forms interwoven near and far into a community.

If this seems an unusually intimate and faithful blend of science and art, that’s doubtless because Marshall has a foot in both camps. She graduated in biochemistry from Oxford in 1997 before training in fine art and turning to sculpture. In 2011 she became sculptor in residence at the Pangolin London studio at the King’s Place. This exhibition marks the culmination of that residency.

‘Having a scientific training, you view the world through that lens, you can’t escape it,’ she has told me. Some of her earlier work focused on the forms of enzymes, rendered as more abstract, smooth-contoured shapes in which substrates made from humanoid figures might be found dancing in the binding sites, clinging to the slopes with precarious purchase. This incorporation of a human element helps observers appreciate what might otherwise seem an unfamiliar, alien landscape and to find their own metaphorical meanings within it. ‘When there are figures in the work, people find it easier because they can relate to it at other levels,’ says Marshall.

Her most recent work moves beyond the molecular scale. In Embryo spiral, a logarithmic spiral in copper wire unfurls elegantly from a fetus, paying homage to Fibonacci and D’Arcy Thompson. And Carnegie stages is a series of five forms representing the embryo in its earliest stages, as the primitive streak that defines the basic axis of bilateral symmetry appears. It’s a latent human body, but could also be that of almost any vertebrate: that double-helical genome has not yet imprinted its unique identity on this natural example of symmetry-breaking. The exhibition presents these shapes at very different scales: a neat row of bronzes barely six inches high, and a series of resin forms each the size of a coffee table, dangling from the ceiling.

I’m not an impartial reviewer; having previously interviewed Briony in her west-London studio, I have contributed an essay to the catalogue exhibition. But don’t take my word for it: come to the exhibition and see whether you feel Marshall’s vision of life forming succeeds in adapting the chemists’ and anatomists’ tradition of physical model-building into a genuine art form.

No comments yet