A heating device from a fan of heated disputes

A few days ago a student walked by me in the lab as I was doing a small-scale distillation; she did a double-take at the ‘ancient’ heater-stirrer I was using, which, to me, seemed no older than she was. It made me wonder: what is the oldest bit of regularly used kit in our department? Might there be something as old as I am?

It was in our big teaching lab that I spotted them: the steam baths that students use for recrystallisation. Made by Griffin and George, one of the legendary British scientific equipment suppliers, the metal boxes, with their concentric circular lids of different sizes, have survived for well over a half a century.

The inventor of this simple device was an innovative and reactionary Scottish chemist who has the distinction of having been taken to task by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in their incendiary economic and political critique Capital.

Andrew Ure became notorious for both his flamboyant showmanship and his readiness to get into violent arguments with colleagues and competitors. He may have inherited his short temper from his father, a Glasgow cheesemonger. Instead of joining the family business, Ure went off to study medicine. His furious father left him out of his will. When he discovered this, Ure ripped the will from the lawyer’s hands and tossed it into the fireplace.

Ure did not last long as a medic. He secured the chair of natural philosophy at the Andersonian Institution in Glasgow, and began giving evening lectures in chemistry and in mechanics. It was a tough gig. The position was unpaid, had no budget and no lecture space; subscriptions were the only source of funds. Ure set about putting together lectures peppered with demonstrations. By installing the first gas lighting in Glasgow he cemented a reputation as an innovator. He was clearly a great speaker because his classes often attracted hundreds of members of the public, despite the unreliable lighting that sometimes left the whole space in darkness.

Ure waxed lyrical about the benefits of his classes: ‘A taste for science elevates the character and creates a disrelish and disgust at the debasement of intoxication. Philosophy dressed in attractive garb leads away from the temptation of the tavern.’ The success of his programme would inspire others to set up analogous institutions.

In 1807 Ure married and started a family. He got himself appointed as professor of astronomy – a subject he doesn’t seem to have known much about – at a new observatory. It prompted some satirical comment about his pomposity and arrogance. By 1818, however, his life was increasingly turbulent. His wife had an affair with a fellow professor, leading to a very public and acrimonious divorce. Then in a vitriolic paper, he accused the professor of chemistry at the University of Glasgow, Thomas Thomson, of having fudged data in his work on atomic weights. While Ure was right that some of Thomson’s figures were wrong, the dispute did him no favours.

In 1807, Ure married and started a family. He got himself appointed as professor of astronomy – a subject he doesn’t seem to have known much about – at a new observatory. It prompted some satirical comment about his pomposity and arrogance. Ure began lecturing in Belfast during the summer, a short-lived activity that put him into contact with the Linen Board in Dublin. The linen industry then derived much of the alkali required for the bleaching of the fibres from kelp and barilla. Its quality varied hugely. Ure developed an ‘alkalimeter’, an early volumetric device to assess the quality of the alkali. It eventually led Ure to the idea that the concentrations of acids and alkalis could be quantified in terms of their ratio or ‘equivalents’, introducing the concept of normality into chemical analysis.

If it ain’t broke, keep using it

By 1818, however, his life was increasingly turbulent. His wife had an affair with a fellow professor, leading to a very public and acrimonious divorce. Then in a vitriolic paper, he accused the professor of chemistry at the University of Glasgow, Thomas Thomson, of having fudged data in his work on atomic weights. While Ure was right that some of Thomson’s figures were wrong, the dispute did him no favours. He also unjustly accused William Henry of having stolen his alkalimeter method.

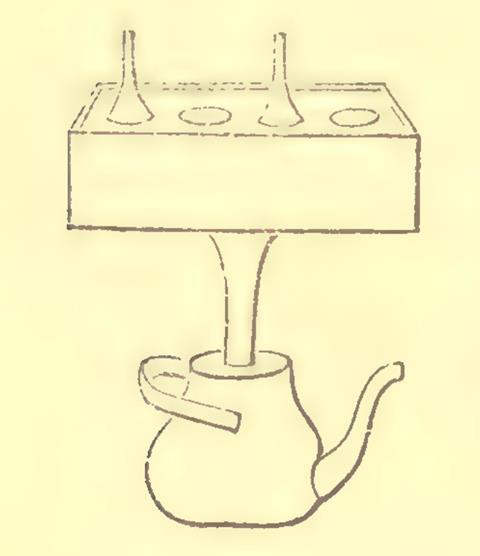

When he was approached to update William Nicholson’s Dictionary of Chemistry, he used the long introduction to rant about his many disputes. In all of this he continued to do some research, publishing articles on many topics from his own laboratory in Glasgow; it was probably where he built his little steam bath. It consisted of a metal box with a lid that had a series of different-sized holes in the top into which one could sit a flask or an evaporating dish. A tube in the base led down to the lid of an ordinary kettle. Filled with water and set on a stove, with the spout well-stoppered, this kettle-steamer was perfect for small scale evaporations or digestions, and was recommended by Michael Faraday.

Ure’s lecturing was now suffering badly. He left Glasgow for London, where he worked as a chemical gun for hire, consulting and acting as an expert witness. He worked on sugar refining, analysis of mineral water, factory ventilation, cotton-making and more. His experiences in factories, especially the mills of the north of England, led him to write his Philosophy of Manufactures, a book full of contradictions that argued that the industrial revolution was unstoppable and that the workers were much better off in factories than on farms. It was this that attracted the summary dismissal by Marx and Engels.

Ure died in London and is buried in Highgate, not far from Marx. His steam baths – electrically heated – are still going. And why not? After all, if it ain’t broke, keep using it. My hotplate seemed to heat and to stir just fine. Could it be that the student was obliquely suggesting that it wasn’t just the kit that was past its use-by date, but perhaps the chemist too?

No comments yet