The creation of a new ministry has put science back on the political agenda in Argentina. Ana Fraile and Federico Williams look at what it means for the future of the country

The creation of a new ministry has put science back on the political agenda in Argentina. Ana Fraile and Federico Williams look at what it means for the future of the country

Recent political history may have overshadowed its achievements, but Argentina has been supporting scientific research and the development of new technologies, at a national level, since the middle of the 20th century.

The National Research Council of Science and Technology (Conicet), the National Institute of Agricultural Technology (INTA), the National Institute of Industrial Technology (INTI), and the National Commission of Atomic Energy (CNEA) were all founded during the 1950s. And all of these institutions, as well as the many science and engineering departments within Argentinean universities, provide the setting for most national scientific research - with relatively little taking place in private institutions.

All of this national investment put Argentina on the world’s scientific stage. There were Nobel prizes for two of its scientists - Bernardo Houssay (physiology or medicine in 1947) and Federico Leloir (chemistry in 1970). And the nation’s nuclear energy and satellite technologies have been successfully developed and are nowadays exported.

But political and economic crises have done continued damage, causing thousands of scientists to emigrate, centres and institutes to close their doors, and a chronic lack of funding for research projects and infrastructure (see timeline). It was the return of democracy at the start of the 1980s that allowed the scientific community to begin a discussion about how to revitalise Argentinean science, and to unite the individual research programmes scattered throughout various institutions.

Key dates

1816: Argentina declares independence and becomes a national state

1816: Foundation of the Academy of Mathematics.

1821: Foundation of University of Buenos Aires.

1896: First Chemistry PhD. 1916: First democratic elections.

1918: University statutes are reformed to include student participation in government, a selection process involving interviews and unrestricted access to courses.

1930: First Military Coup.

1930: University of Buenos Aires is disrupted by the military coup.

1943: First national production of penicillin (not funded by the government).

1943: Bernardo Houssay expelled from the laboratory due to his political views.

1947: Houssay wins the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine.

1950-57: Foundation of National Commission of Atomic Energy, National Institute of Agricultural Technology and National Institute of Industrial Technology.

1958: Refoundation of National Council of Technology and Scientific Research. Bernardo Houssay appointed as director.

1966: Night of the long police batons. On the 29 July military groups, lead by General Ongan?a, enter universities, laboratories and libraries. 400 people were imprisoned and 301 Professors emigrate - 215 of whom were scientists. 1970: Federico Leloir wins Nobel Prize in chemistry.

1976: Military Coup. 30 000 people are kidnapped, tortured and killed by the military regime. Most of their bodies are still missing. Many professors and intellectuals emigrate.

1983: Democratic elections in December. Reconstruction of democratic governments in universities and scientific institutions.

1984: Cesar Milstein, Argentine scientist who was made to leave the country in 1962, wins the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for his research carried out at Cambridge, UK.

1996: Creation of the National Agency for Science and Technology Promotion. It’s the first funding body to fund research across institutions in the nation.

2001: Economic and political crisis. GDP drops 64 per cent. Operation of institutions as well as funding of scientific research is halted.

2008: Creation of the Ministry of Science Technology and Productive Innovation.

Almost 30 years later, the country has brought science into sharp national focus once again, with a new ministry within its democratically-elected government.

When Cristina Fernandez won the general election in 2007, she made a bold decision to create the Ministry of Science, Technology and Productive Innovation.

Keeping the peace

To many it may seem a tall order for Argentina to once again produce world class science. Decades of economic and political unrest, negative state policies and lack of government funding dismantled a social system which had boasted European living standards in a Latin American country. Poor leadership and misguided or corrupt management of state coffers progressively looted national education and health. And, by the end of the 20th century, valuable Argentinean exports were minimal - the state had fragmented and become powerless.

But a renewed sense of hope has been quickly followed by evidence of positive change. Since the last economic crisis in December 2001, Argentina’s economy has grown 8-10 per cent each year, according to figures from the Inter-American Development Bank, calculated on the basis of industrial exports.

And the government has nationally trumpeted the revitalisation of the economy - in part to settle the huge social anxiety and unrest generated by repeated periods of crisis. It has become a key priority for the government to develop and strengthen industry and productivity - adding value to the export market through innovative technological developments. So the development of science and technology became a central state policy.

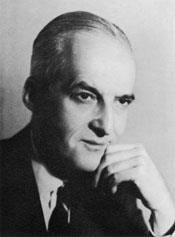

The main objective of the new ministry is to grow science and technology, both to solve national health and social problems, and to boost the economy by increasing the technologies transferred to the commercial sector. Leading this new national project is the molecular biologist and now science minister, Lino Bara?ao.

First in class

Bara?ao chose to pursue science in order to ’study and understand the world’. ’[It] gives me great satisfaction,’ he says. At the age of 22 he started a PhD studying mechanisms of action of hormones during reproduction, developmentand disease.

When he completed this in 1980, like many of the country’s doctoral students, he moved abroad to continue his research in chemical biology at Penn State University in the US. He describes his days as a postdoc as ’idyllic’ - ’years that gave me the time and resources to think and do research’.

Bara?ao excelled in his academic career and soon returned to Argentina, where he started his own research group at the University of Buenos Aires. He launched a laboratory focusing on biotechnology, with the aim of generating innovative new technologies - maintaining his strong conviction that this was possible in the Argentinean academic environment. It took his research group 18 years of continuous work in the field to develop the technology to genetically modify and clone bovines. (Argentina was the first Latin American country to develop two generations of cloned cows and is one of only nine nations in the world to control the technology to clone livestock.)

After this, Bara?ao created the first centre in Argentina to develop spin-out companies based on academic research, starting his path in the management of science.

As science minister, he is now the key figure in the development of science and technology in Argentina. And it’s a challenge to develop and commercialise high tech innovations in a country where the number of companies demanding high-end technologies is very small.

But the new minister is convinced that this is key to the future of Argentina’s economy. ’We need to create more companies led by professionals and business people aware of the importance of the permanent technological innovation demanded in the world markets nowadays,’ he says. ’This way, we will be creating more job vacancies, encouraging social inclusion, and diversifying the national productive model towards a model of a technology based on knowledge.’

Despite its ambitious goals, the creation of the ministry of science went almost unnoticed by the bulk of Argentinean society. But Bara?ao thinks that with time and effort it will start to make its presence felt outside of the scientific and political communities. ’Scientists need to produce something that the Argentinean society can see, besides contributing to the advancement of science [itself],’ he says. His ministry is faced with the task of demonstrating to the whole of society that without education, science and technology there is no possibility for development in the country. ’I believe we can achieve this cultural change,’ Bara?ao adds.

New priorities

The scientific community has applauded the development. Many of Argentina’s scientists appreciate the important political gesture after many years of government policies that dismantled scientific institutions. And there is optimism that science is being treated as a valuable and important tool that merits inclusion in state policy.

But some are concerned with the availability of funds to support research, increase salaries, rebuild infrastructure and generate new institutes. The extremely low budget for science in the past asphyxiated its growth. And economic, political and social instabilities have disrupted many research groups, pushing scientists to emigrate. The Argentine Nobel prize-winning biochemist Cesar Milstein (physiology or medicine in 1984), for example, left the country in 1962 and spent most of his career at the University of Cambridge, UK. There are few cases of scientists who have been able to develop and compete internationally from Argentina, but Milstein and many of his generation were only able to achieve their goals abroad.

The tide began to turn years before science took its official place in within a state ministry. In 1996 the National Agency of Scientific and Technological Promotion was created. The agency divides funding into two categories: research groups working in not-for-profit institutions, generating new scientific or technological knowledge; and scientists working to improve production of the industrial sector through technological innovation. It will continue to be the main funding body of research projects in the country.

Now the aim is to restore and rebuild Argentinean science, with increased funding for equipment, infrastructure and the refurbishment of old laboratories. The ministry is also implementing policies that will continue to facilitate the easy repatriation of Argentinean scientists working abroad who want to return home, as well as the promotion of young and early career researchers.

Bara?ao is pragmatic, and says he does not want to discount the needs of the Argentinean society for the sake of bold scientific and technological targets. His current funding goal is for a modest 1 per cent of GDP to be spent on science, and there is now very slow but steady progress towards that goal. According to ministry figures the amount spent on R&D increased from 0.4 to 0.5 per cent of GDP between 1996 and 2006.

Initially the ministry established two main priorities. The first is to create high technology companies based on knowledge arising from scientific research in the areas of nanotechnology, biotechnology and information and communication technology. The second is to solve structural problems related to energy, health, agriculture and social development.

’I believe our goal is to accomplish two or three fundamental milestones - eradicate a disease, generate a new product or a new crop for export, or increase the competitiveness of a specific sector from the incorporation of a new technology. That is our challenge,’ he says.

There are a few sceptics, but most scientists believe that, providing there is long term political and economical stability, the ministry will have a positive influence on the progress of the Argentine society.

Recent history may not encourage confidence. Between the end of 1950s and early 1960s Argentina made a huge progress in basic science and technology development. But just over a decade of achievement was driven into reverse during the successive military and failed democratic governments that led the country to extreme poverty.

The first challenge for the current government is to improve the quality of life for Argentinean people, and the creation of the science ministry is part of that strategy to restart the nation’s development. Whether this is feasible, and how much of a direct role the new ministry will play, remains to be seen. But Argentina has placed confidence in its own ability to remain stable and grow - challenging the pattern of its own history.

Ana Fraile and Federico Williams are freelance science writers based in Buenos Aires, Argentina

Date of birth 28 December 1953

Nationality Argentine

Work experience

1984-current Principal researcher, National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (Conicet) Associateprofessor, University of Buenos AiresMinister of Science, Technology and Productive Innovation

1982-84 Project associate, division of endocrinology, The Milton S. Hershey Medical Center of The Pennsylvania State University, US

1981-82 Visiting fellow, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Endocrinology and Reproduction Research Branch, Bethesda, Maryland, US

1981 Researcher, Max Planck Institute for Psychiatry, Munich, Germany

1976-81 Research associate, Institute of Biology and Experimental Medicine

1976 Research assistant, Institute of Biology and Experimental Medicine

1973 Research assistant, University of Buenos Aires

Education

Chemistry PhD, University of Buenos Aires, 1981

Chemistry BSc, University of Buenos Aires, 1976

Milestone

Led the research team that developed the technology to clone livestock, succesfully cloning the first cow in Latin America in 2002. As a result Argentina is one of the nine countries in the world to commercialise this technology.

No comments yet