The end of ovulation will affect almost all women, but current treatments could be improved. Rachel Brazil reports on the efforts to find a better solution

-

Menopause symptoms and treatments: The article discusses common menopause symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweats and increased risks of heart disease and osteoporosis. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is highlighted as a common treatment, though it has faced controversy and evolving perceptions over the years.

-

Advances in HRT: Recent advancements in HRT include the use of body-identical hormones and transdermal patches, which reduce risks like blood clots. However, concerns remain about unregulated bioidentical hormones, which claim to offer personalised treatments but lack scientific backing.

-

Innovative therapies: The article explores new approaches to menopause management, such as cell therapy implants that mimic ovarian function and deliver a balanced mix of hormones. These innovations aim to provide more natural and responsive hormone replacement options.

-

Delaying menopause: Researchers are investigating ways to delay menopause to extend fertility and reduce health risks associated with post-menopausal life. This includes studying drugs like rapamycin and anti-fibrotic treatments to maintain ovarian function and delay the onset of menopause.

This summary was generated by AI and checked by a human editor

For a long time talking about vaginal dryness, painful intercourse, urinary insufficiency and many of the other symptoms that come along with menopause were not things women felt comfortable sharing. ‘It was a taboo topic and therefore was not addressed,’ says Dina Radenkovic Turner, co-founder and chief executive at Gameto, a company dedicated to redefining female reproductive health, based in Texas, US. This is in common with many other medical issues that only or disproportionately affect women (see Fixing medicine’s blind spot on women’s health). But Radenkovic Turner hopes the tide is turning, with women now more open about their menopause, which in turn is stimulating more interest in finding solutions.

Menopause occurs when women cease ovulation, usually between 45 and 55 years of age, leading to oestrogen and progesterone levels sharply falling over a typical period of two years. The common result is symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweats and trouble sleeping. The hormones themselves also have a protective effect, and without them there is evidence that woman are at higher risk of heart disease and osteoporosis. Most recently, research has linked increased menopause symptoms to a higher risk of dementia.

One of the most well-established ways to treat the symptoms of menopause is hormone replacement therapy (HRT), which supplements the reproductive hormones oestrogen and progesterone that are lost when ovulation ends. But HRT has had a rocky road since it was first prescribed in the early 1940s. Its use became widespread during the 1960s, but in 2002 results of a trial from the US Women’s Health Initiative indicated that HRT could increase breast cancer and heart attack risk. The number of women taking HRT decreased by 38% in a year and by 2009 it was down 70%.

It turned out that researchers had misinterpreted the study’s initial results because they had not been adjusted for participants’ preexisting diseases, and they had generalised findings to all postmenopausal women regardless of age. Ultimately the results were not statistically significant for breast cancer harm or for heart attacks, with the only significant findings an increase in venous blood clots and a reduction in hip fractures. By 2013 one of the original authors lambasted the publication and press release as ‘fear and sensationalism over science’.

More recent studies show HRT does carry a small risk, with around five extra cases of breast cancer in every thousand women who take combined HRT for five years. Some studies have detected subtle differences in risk factors, depending on the type of HRT given. Most HRT products now contain body-identical hormones rather than analogues of the natural hormone molecules; for example, there has been a shift from traditionally used oestrogens extracted from the urine of pregnant horses, known as conjugated equine oestrogens (CEEs), to 17-beta oestradiol, the primary member of the oestrogen hormone family produced by humans. 17-beta oestradiol is synthesised by enzymatically converting a steroid like testosterone or it can be synthesised from diosgenin, a plant steroid found in wild yams and soybeans.

Using natural progesterone is slightly more complicated because the natural hormone cannot be taken orally. But in the 1980s Schering-Plough developed an oral ‘micronised’ progesterone, made from progesterone synthesised from diosgenin. The progesterone is finely ground so it can be absorbed into the bloodstream. The older hormone analogues were able to bind to off-target receptors leading to unwanted side effects not found with body-identical hormones, which may also reduce breast cancer risks, but ‘the differential is tiny’, according to Paula Briggs a consultant in sexual and reproductive health based at Liverpool Women’s NHS Foundation Trust. ‘I think it’s being massively exaggerated,’ she says.

Delivering better hormone replacements

Clinicians like Briggs are most concerned at the growth of what are sometimes called bioidentical hormones – a potential downside to the growing visibility of menopause care. Produced as creams by specialist compounding pharmacies which claim to make bespoke formulations, they are based on untested claims that serum and saliva tests can determine the precise hormone requirements of each woman. The mixtures of hormones also claim to balance different forms of oestrogen, although there is no evidence to support that this is beneficial and experts have concerns that women may be exposed to higher oestrogen levels than necessary or, in the case of progesterone, not enough. These products are unregulated and Briggs worries woman are being given ‘skewed’ information. ‘Even more educated women would struggle with the kind of subtle differences between these hormones,’ she says.

One change that has been largely embraced is a shift from oral medication to HRT transdermal patches which reduce cases of blood clots, a risk in some women using HRT. As well as avoiding the harsh environment of the gastrointestinal tract, transdermal delivery allows for a more constant hormone flow, according to David Haddleton, a polymer chemist at the University of Warwick, UK, who has developed a new patch technology. He is using it in the first instance to deliver the hormone testosterone to women, as its levels can decline during menopause. While testosterone is not part of conventional HRT, it has been approved for treating women experiencing low libido. But currently there is no European product designed for women and they often end up using a cream or gel designed for men, making it difficult to gauge the right dose.

Haddleton’s spin out company Medherant is using unique polymer science for his first-in-the-world testosterone patch for women, which is currently in clinical trials and he hopes will be on the market by 2028. His technology has the advantage of improved adhesion and less cold flow – the process by which adhesive starts to migrate at body-temperature, leaving sticky black marks on the body. He has achieved this using a silylated polyether–urea rather than the commonly used polyurethane. When exposed to moisture in the presence of a titanium catalyst the silylated groups are cross-linked, forming a solvent-free adhesive. ‘We cross-link it with exactly the same chemistry that you do with a kitchen sealant,’ says Haddleton, but the drug is dissolved into the adhesive alongside an excipient which helps the drug diffuse across the skin. The adhesive shows no cold flow, and its strength could be fine-tuned by adjusting the level of silylation. Haddleton is hoping to eventually follow this up with an oestrogen and progesterone patch.

But ‘one size fits all’ hormone replacement may not be the best approach according to Radenkovic Turner. Her company Gameto is developing a cell therapy that can more closely mimic the way an ovary functions and allows them to replace the full cocktail of hormones they produce, she says, ‘which is certainly not just oestrogen and progesterone, but also low level androgens (testosterone) and certain growth factors’. Their real-time personalised hormone replacement cell-therapy implant is at a pre-clinical stage and is being first developed for women suffering from ovarian insufficiency, also known as early menopause.

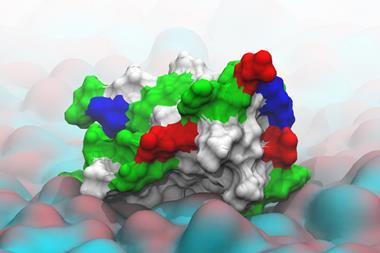

Ameno, Gameto’s implantable device, houses ovarian hormone-producing cells engineered from stem cells in five days, using technology developed by Gameto’s chief scientific officer, Christian Kramme, during his PhD in George Church’s synthetic biology lab at Harvard Medical School in the US. Thousands of these cells are contained in microbeads made from alginate (a polysaccharide extracted from brown algae). These contain a matrix of laminins – large glycoproteins found in supporting tissue – to which the cells attach, resembling an ovarian follicle, the part of the ovary where an egg is matured. This system shields the cells from the body’s immune response when implanted, although Kramme says they are working on additional immune-shielding coatings to improve longevity. The microbeads will be implanted under the skin in a rod-shaped resin device which has small pores in the sides that allow nutrients and hormones to exchange into the bloodstream.

The hormone-producing cells in the device are in constant dialogue with the brain, which itself produces hormones, creating a dynamic feedback loop which replicates the type of hormone cycling occurring naturally in ovulating women. This avoids the type of artificial hormone spikes and longer exposures that a patch or tablet will produce. ‘The beauty of this solution is that the cells are responsive, and they respond to the hormones that are present in the body of each women,’ says Kramme. ‘It’s essentially serving as a third ovary.’

The company envisage such an implant could be inserted and then removed in an outpatient procedure after one to five years, depending on age, to stop the abrupt changes that occur with menopause. ‘Eight out of 10 women have really bad symptoms in this first two years, because [that’s when] you lose 80% of hormones,’ says Radenkovic Turner. Her hope is that cell therapy could bridge that gap and allow a slower tapering down of hormone levels, while also slowing the onset of post-menopausal conditions like osteoporosis by another decade.

Delayed benefits

Rather than replacing or replicating hormone production, others are looking at ways to delay menopause itself, both to extend a women’s fertility and lessen its negative effects. ‘Most women will live into their 80s, so that means women are going to be living three decades in a post-menopausal state,’ says Francesca Duncan, a reproductive scientist at Northwestern University in Illinois, US. ‘I’m very interested in saying “Can we actually extend the function of our ovaries, so we don’t have to rely on potentially assisted reproduction or hormone replacement therapy, which are in effect like band aid solutions?”’

This delay could also have significant benefits to women’s health as oestrogen plays a positive role in cardiovascular, brain, immune and bone health. ‘As long as you have a functioning ovary, women have this health advantage over men,’ says Zev Williams, an endocrinologist and infertility expert at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, US. ‘So if we can find a way to tune the lifespan of the ovary to more accurately reflect the lifespan of the woman, you can extend the health benefit.’

Williams’ work started with the genetic condition fragile X syndrome (FXS) which causes intellectual disabilities but also premature menopause in women. Researchers have shown that the syndrome is caused by a mutation on the X chromasome that prevents the production of the protein FMR1, which is needed for the development of synapses. Another repercussion is the over-activation of mTOR – the mammalian target of rapamycin, a cell growth regulating kinase. It’s named after the drug molecule rapamycin, which can inhibit the kinase and is widely used as an immunosuppressant for transplant patients.

Rapamycin has an unusual provenance, after which it is named. It was first found in soil samples by a 1964 Canadian expedition to Rapa Nui, also known as Easter Island. In 1972 chemists at Ayerst Pharmaceuticals isolated the compound for use as an antifungal agent, with subsequent research discovering its immunosuppressive properties as well as potential anti-cancer activity. A 2009 study showed the drug could increase the lifespan of mice, even when administered at an older age. Could this link to longevity also be relevant to delaying menopause?

Williams started experimenting on knock-out mice with the gene involved in FXS removed and found rapamycin could reverse the premature ovarian failure found in FXS. ‘What was surprising was our control group, which were normal mice who were given rapamycin, had an extension of their reproductive lifespan, so they were doing better than normal,’ he explains. The drug was able to slow down the rate at which eggs were depleted from the ovary each month.

In 2024 he launched a placebo-controlled study in 50 women aged 38–45 to see if the drug, given weekly, would have a similar impact on human fertility. The blinded study is yet to report, but ‘we’re already seeing tantalising clues that this might be helping’, Williams says. ‘One group is reporting better energy, better mood, better memory, [and a] better sense of overall well-being.’ If the results are ultimately positive Williams says the drug has been so widely studied and is available at a low cost, so if the results are ultimately positive Williams thinks it could be rapidly translated into an intervention that could make a meaningful difference for millions of women.

It’s not a disease

Duncan is taking a different approach which she hopes might also lead to a delay in menopause. She has been looking at some of the changes that happen as ovarian tissue ages and tends to become more fibrous due to the constant monthly renewal of tissue occurring in the ovary. ’At a certain point, you just overwhelm the system, and it can’t keep up and then that sets off this cycle of inflammation and fibrosis,’ she says. That ‘stiff’ environment then stops the proper growth of the follicles housing the developing eggs and she explains that this leads to a spiral of insufficient hormone production, poor quality eggs and ultimately menopause.

Duncan’s team had observed this change in ovarian tissue in mice when removing eggs for another study. ‘It was really hard to get the eggs from the old ovaries out of the tissue because the tissue was physically just tougher.’ It’s known that with age many organs become more fibrous due to deposition of extracellular tissues containing collagen and the glycoprotein fibronectin, accompanied by increased inflammation, but Duncan found it was occurring much earlier in the ovary. In 2016 she showed that the same inflammation and fibrosis could be seen in aging human ovaries which she says ‘shifted the paradigm in the field’.

Since then Duncan has been looking for a therapeutic target to reduce this process and homed in on the anti-fibrotic drug pirfenidone which breaks down collagen and is approved to treat idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a progressive lung disease characterised by scarring of the lung tissue. They treated mice from around seven months old, which Duncan says is equivalent to a human in their late 20s. ‘We were able to show that there was a sustained decrease in fibrotic tissue, a decrease in the inflammatory response and then this translated into better reproductive outcomes in terms of hormone production, the architecture of the ovary and follicle numbers,’ she says.

Duncan is thinking about how this could be transferred into a therapy for women. Pirfenidone shows liver toxicity in humans, so isn’t an ideal drug for a healthy population, so she is looking for safer alternatives or an alternative target involved in driving the fibrosis.

How much of a delay these kinds of therapies might offer is not yet known, but it won’t be indefinite. ‘We’re going to be constantly moving against this natural winnowing of the ovarian follicles,’ says Duncan, but she thinks it must be preferable to the current use of hormones given at non-physiological doses. ’If you can just keep the normal organ functioning in its natural state, why would you rely on hormones exogenously?’

Could delaying menopause be standard practice in the future? While Duncan acknowledges ‘menopause is not a disease, it’s a part of our physiology’, she says. ‘If you think about how we’re changing the way we live, it has put women at a health disadvantage.’ Radenkovic Turner also sees the pros: ‘Now that we’re living much longer, I think we’re now starting to understand the consequences of menopause on the broader women’s health.’ But not every woman is likely to be keen on delaying their menopause. ’It sounds horrific to me,’ says Briggs. ‘There are some things about menopause that are good. You stop having periods, you stop having premenstrual disorders. We’ve all got to age.’

Rachel Brazil is a science writer based in London, UK

No comments yet