The European Research Council officially comes to life this month, promising to fund basic research and to move away from an EU focus on multi-centre collaborations. Arthur Rogers finds out more

The European Research Council officially comes to life this month, promising to fund basic research and to move away from an EU focus on multi-centre collaborations. Arthur Rogers finds out more

Hurriedly launched at the turn of the year, the European Union’s €50.5 billion (?34 billion) seventh framework research programme (FP7) offers prospects of more funding and a distinct shift in EU research policy, in the form of the European Research Council (ERC).

Almost 150 years after Abraham Lincoln approved the creation of the American Academy of Sciences, the EU is also beginning to think about research at a continental scale and to acknowledge the role of basic research in stimulating innovation.

The ERC is the first manifestation of this new approach. This body was created on the strength of a 2003 report from a group of research experts convened by the European commission which included John Taylor, then director general of Research Councils UK.

The report argued that ’the first and main task for the ERC should be to support investigator-driven research of the highest quality selected through European competition’.

While funding decisions should be based on scientific criteria, and use a rigorous and transparent peer process, the ERC should ’encourage interdisciplinary and risk-taking projects, especially in emerging research areas,’ the group’s report recommended.

Those ideas have been carried through to the FP7 legislation, a chapter of which formally authorises the establishment of the ERC as a body largely independent of the EU institutions and managed solely by the international research community.

The chapter, entitled ’ideas’, authorises the ERC to encourage ’frontier research’ - a euphemism for basic research - from a budget of €7.5 billion for 2007-2013. The funding amounts to barely half the figure recommended in the 2003 report, which proposed an annual allocation of €2 billion.

But then FP7, like other areas of expenditure, has been hit by the national leaders’ decision at the 2005 Hampton Court, UK, summit to set an overall ceiling on EU spending for the next seven years.

The decision meant that research commissioner Janez Potocnik’s planned FP7 budget was slashed overnight by more than €22 billion.

The Slovenian commissioner nevertheless calculates that the reduced €50.5 billion FP7 budget can disburse 40 per cent more funding each year compared with the previous programme. And he hopes that national leaders will reconsider when the EU budget cap is reviewed in 2010.

Confidence boost

A successful launch of an autonomous ERC will inspire confidence around Europe’s capitals, and help persuade ministers to ease the ceiling on research spending, Potocnik told journalists when FP7 was signed off by the European parliament. The parliament confirmed that the ERC should focus on ’interdisciplinary, high-risk pioneering projects and new groups, and less experienced researchers as well as established teams’.

’This change of course is overdue,’ says German Christian Democrat MEP Angelika Niebler, who served as the parliament’s rapporteur on ideas.

She foresees that the ERC can help to create ’urgently needed’ conditions that may persuade leading researchers to remain in Europe and attract outsiders.

’Even though basic research can produce knowledge that leads to substantial follow-up investigations, basic research has hitherto lagged significantly behind applied research when it comes to attracting EU support,’ says Niebler.

’Private finance is hard to attract because basic research carries with it considerable financial risks and does not automatically promise marketable products, so it is therefore understandable that the idea of the ERC has received massive support from the research community,’ she adds.

Frontier science

The project attracted a positively lyrical endorsement from number crunchers on the parliament’s budgets committee.

Greek rapporteur Marilisa Xenogiannakopoulou declared that the ideas programme will ’provide a pan-European mechanism to support the truly creative scientists, engineers and scholars, whose curiosity and thirst for knowledge are most likely to make the unpredictable and spectacular discoveries that can change the course of human understanding’.

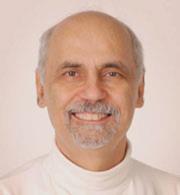

Meanwhile, the groundwork for the ERC has been laid - on a voluntary basis - by a 22-member scientific council made up of leading scientists, engineers, scholars and research leaders headed by the molecular biologist Fotis Kafatos, of Imperial College London, UK, where he holds the chair of insect immunogenetics.

Successive EU framework programmes since 1984 have served almost as bonding exercises for Europe’s research community, by helping to fund cross-border research collaborations.

Politicians have justified this use of taxpayers’ money by pointing to the need to support collective EU policies, not least the need to underpin Europe’s economy by promoting applied science.

The ERC project will not only mark a return to basic science, but a relaxation of the bias toward multi-centre collaborations.

’We will still support collaborations, but all proposals - whether from an individual, an individual team or ones involving collaboration - will be assessed on the sole criterion of scientific excellence, rather than industrial applicability or geographic considerations,’ Kafatos tells Chemistry World.

There will be ’no cookie points’ for collaborations per se; rather, collaborative proposals must be able to demonstrate added value, he explains.

’Using the term frontier science isn’t such a bad way to emphasise that we’re now trying to identify and fund not just good basic research, but really excellent basic research which is capable of moving forward the frontiers of knowledge,’ says Kafatos.

’The agenda is clear: we have been entrusted with a fundamental, excellence-based, investigator-initiated approach that is bottom-up rather than top-down. That is going to make a big difference in Europe because it opens up the opportunity of creative, top quality research in all fields,’ he adds.

Leadership splits

One of the scientific council’s biggest tasks over the past year has been to settle the leadership of the ERC during its first five years.

Ernst-Ludwig Winnacker, the biochemist who heads the German Research Foundation (DFG), Europe’s biggest research funding agency, became the ERC’s first secretary general at the turn of the year, and will hand over in mid-2009 to the Catalan economist, Andreu Mas-Colell.

In three terms at the DFG Winnacker is credited with driving through organisational reforms, while Mas-Colell similarly has a track record of institution building from a spell as Catalonia’s minister for universities and research.

Splitting a five-year tenure between two candidates is a device traditionally favoured by the EU as a way of placating opposing factions when two heavily backed candidates are in contention. This form of job sharing has been used to settle, for example, the presidencies of the European Central Bank and even that of the European parliament.

The European commission foresees Kafatos and the scientific council concentrating on developing an overall science strategy and drawing up a work programme for the ERC, which will then handle implementation. Importantly, the scientific council will devise the criteria that will form the basis for decisions on the funding.

A smokescreen of EU jargon has obscured the actuality that the ERC is a de facto independent executive agency of the European Union, a status almost certain to be confirmed de jure when its progress is independently reviewed in 2010.

The political difficulty here is that the EU is spawning such agencies at such a rate that MEPs increasingly grumble that they have to vote on agency budgets without being able to exercise oversight of activities hitherto authorised through legislative measures.

No fewer than 19 agencies have been established to date, with four more ’under preparation’, including the Helsinki-based European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) tasked with administering Europe’s newly approved Reach (Registration, evaluation, authorisation and restriction of chemicals) regime on chemicals.

In cases such as that of the ECHA, the parliament has fought to secure seats on the governing board of agencies, but regarding the scientific council, the parliament is not yet pushing for representation in a body supposedly free from all political influence.

Even so, Niebler points out that committee members and the director of the American National Science Foundation, for example, must be nominated by the US president and confirmed by the Senate, while in the German research community both the federal and state governments have a role in establishing research guidelines and taking decisions, even on individual projects.

Europe-wide research

On the understanding that the first three years will be akin to a trial period, MEPs are settling for regular reports on ERC activity, and rotation of the membership of the scientific council, to avoid it becoming a ’closed shop’.

As for commission claims on the ERC budget, the parliament has only granted up to 5 per cent of the total ideas budget to cover administration and staff costs in Brussels, to ensure that the maximum possible funding goes to research.

At the institutional level, Kafatos foresees that the ERC will position itself as ’a research council for all Europe,’ at least in terms of ethos. Thus, it will not encroach upon the competences of either national research agencies or the Strasbourg-based European Science Foundation (ESF).

The ESF, created in 1974, predates the EU’s framework research programmes by a decade, and has a membership of 78 funding agencies, research-performing agencies and academies in 30 countries.

The ESF supports cross-border collaborative research programmes which can involve as many as 20 or more contributing organisations and has a wider mandate to promote science, scientific research, and policy education.

Kafatos sees the ESF moving increasingly into a position where it performs the important task of helping to shape international research policy.

A US model?

On the wider scene, Kafatos contests the suggestion that the ERC is a step towards adopting The American Way, notwithstanding suggestions from European commission president Jos? Manuel Barroso that the EU needs a European Institute of Technology (EIT) that enjoys the stature of the Massachusetts original. (Here, the European parliament insists that Barroso will have to find EIT funding from other sources, rather than raiding the FP7 budget).

At least half the members of the scientific council, including Kafatos, have spent time teaching or studying in the US. Kafatos acknowledges that this is evidence that ’much more needs to be done’ to improve the climate for research in Europe, as evidenced by Europe’s poor showing in the Nobel prize listings.

’You just need to look at what is happening in Asia, where there is a tremendous push forward in science. China, for example, is focusing on fundamental research with a vengeance and bringing back on a massive scale the generation of scientists who were trained mostly in the US following the Cultural Revolution. Japan also is moving away from its European-style top down approach to research.

’It would be a grievous mistake to see the issue simply as a transatlantic competition between Europe and the United States for pre-eminence in science, or that we should see the answers are there [in the United States] ready, and we just need to take them over,’ says Kafatos.

The boundaries between science are becoming ever more fluid and the European Scientific Council has already adopted a policy that applications for funding will be scrutinised by mixed, interdisciplinary panels, he says. ’Interdisciplinarity has not been well handled in the United States, and it remains to be seen who can do it best.’

’Again, much of Europe has neglected the cultivation, mentoring and promotion of our young scientists, more so in continental Europe than in the UK, and we need to change that,’ says Kafatos. The European Research Council could be just the thing to achieve this goal.

Arthur Rogers is a freelance science writer based in Oxford, UK.

Further Reading

For more information on the ERC and its Scientific Council, go to the website.

No comments yet