BASF's decisive step toward starting commercial production of biopolymers for making plastics

German chemical giant BASF has taken a decisive step toward starting commercial production of biopolymers for making plastics, announcing that it is financing research at Graz University of Technology in Austria to determine the feasibility of large-scale production.

In an interview with Chemistry World, Arnold Schneller, head of biopolymers research at BASF headquarters in Ludwigshafen, Germany, said scientists at TU Graz will focus on methods to drive down the cost of biopolymers, which are currently several times more expensive to produce than crude-oil-based polymers.

Schneller said the quality of the polyester PHB (poly-3-hydroxybutyrate) produced from biopolymers is comparable to polyolefins, widely used to make plastics. But BASF will not invest in a commercial biopolymer production plant unless it makes business sense. ’Researchers at the universities are interested in the Nobel prize,’ he said. ’We are interested in the money.’

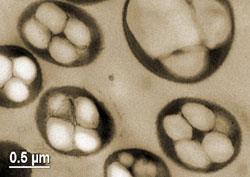

Schneller said biopolymer production currently includes several more costly steps than crude oil-based polymer production. Biopolymer production begins with fermentation during which bacteria gorge on biomass nutrients, such as glucose, sucrose, glycerol, whey, or palm oil, which could be supplied from waste material. When the bacteria are nice and fat, they are killed with heat or chemicals and the raw biopolymer material extracted, which unlike crude polymer, then has to go through several more processing steps. Schneller says three kilos of biomass produce one kilo of biopolymers.

While BASF is still only flirting with the idea of large-scale biopolymer production, global agricultural processor ADM has already invested, forming a joint venture with Cambridge, Massachusetts-based bioscience firm Metabolix. In April, the two firms announced that the joint venture, called Telles, would build a plant in Iowa expected to start production in 2008 that eventually would produce 50 000 tonnes of plastic under the trade name Mirel.

BASF is financing a well-established biopolymer research team lead by Gerhart Braunegg of the Institute of Biotechnology and Biochemical Engineering at TU Graz. ’He [Braunegg] has a lot of experience,’ said Schneller. ’For us, this is a new area.’

Unlike the bottom-line oriented Schneller, Braunegg tells Chemistry World that he believes biopolymers are already cost-competitive against crude-based polymer for injection moulded plastics, which include such items as plastic coffee cups or carry-out foods containers. Braunegg says his team has produced biopolymers for injection moulding for €1.60 (£1.1) per kilo compared to €1.00 for comparable crude polymers. If BASF were to start such commercial biopolymer production, Braunegg believes the cost would fall to crude levels.

Braunegg concedes that the cost gap for blowing films, used for making plastic bags, is still wide, about €3.50 per kilo for biopolymers to €1.00 for crude polymers. The goal of his team is to develop a BASF blueprint for constructing a first plant to produce up to 100 000 tonnes of biopolymers per year, to shorten the production process, and to ensure consistent high quality. To put that 100 000-tonne goal into perspective, global production of polyolefins in 2004 totaled about 70 million tonnes.

Schneller will not comment on potential production capacity if BASF decides to build a full-scale biopolymer plant, saying: ’We have not yet decided to go forward on a production scale. We have to make sure the process is cost competitive.’

BASF is funding Braunegg’s research team for the next five years, and in return will have rights to use research results for ’commercial exploitation,’ Schneller said, adding that BASF is closely monitoring the research and hoping for quick results.

No comments yet