An antihistamine that improves Alzheimer's symptoms has raised questions about our understanding of the disease

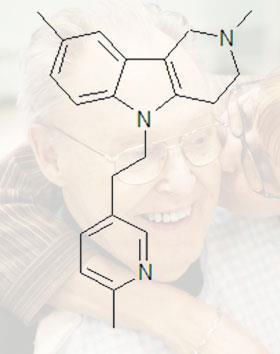

Researchers investigating the causes of Alzheimer’s disease have been left puzzled by data showing that the antihistamine dimebolin, a drug with promising activity in improving Alzheimer’s symptoms, actually seems to increase levels of the toxic protein beta amyloid.

For years it has been thought that the degeneration of nerves seen in Alzheimer’s disease was a result of exposure to the protein fragment beta amyloid. In healthy brains the fragments are broken down and eliminated, while in Alzheimer’s they accumulate to form insoluble plaques.

Results from a Phase II clinical trial reported last year found that dimebolin was around two-and-a-half times more effective than current medicines such as Pfizer and Eisai’s Aricept (donepezil) in improving cognition and memory in Alzheimer’s patients.

The drug’s activity in Alzheimer’s was discovered serendipitously when Russian scientist Sergey Bachurin was screening a number of compounds that could block both cholinesterase and NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartic acid) - the targets for the current generation of Alzheimer’s treatments. It is currently being tested in Phase III clinical trials by US biopharmaceutical firm Medivation in collaboration with Pfizer.

However, results from the latest experiments in mice, reported at a meeting in Vienna last week, indicate that dimebolin actually appears to increase levels of beta amyloid - undermining the idea that the plaques themselves are toxic. The results also raise questions about many of the other drugs that are being developed to treat the disease.

Samuel Gandy of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, who carried out the experiments, told Chemistry World that the findings were surprising. ’Conventional wisdom in the field, regardless of one’s position on ’the amyloid hypothesis’, is that an amyloid benefit would mean amyloid-lowering.’

’The latest findings don’t mean we should toss amyloid,’ he says. ’But we should be prepared to consider unconventional possibilities.’

Clive Ballard, research director of the Alzheimer’s Society in the UK, concurs with that view. ’The data tie in with an alternative hypothesis, namely that other forms of amyloid - such as soluble amyloid oligomers - may actually be more neurotoxic than insoluble plaques, he says.

One school of thought is that plaques may in fact represent a protective mechanism in which the body sequesters toxic forms of amyloid to render them harmless. ’The Gandy research may be showing that dimebolin is driving this process, stimulating conversion of amyloid strands into a non-toxic form,’ suggests Ballard.

The problem for the pharmaceutical sector is that some of the new drugs coming through late-stage clinical testing, including Wyeth and Elan Pharmaceuticals’ much-anticipated antibody bapineuzumab are designed to break down the plaques.

Gandy believes researchers should also be looking at what is going on with amyloid inside nerve cells, rather than the external manifestations of amyloid processing.

’We should perhaps be paying more attention to intracellular oligomers,’ he says. ’There are mice models with elevated intraneuronal oligomers and these show impaired functions, so this is certainly an avenue worth exploring.’

Other drugs in the pharmaceutical pipeline, such as the gamma secretase inhibitor class being developed by Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb and others might lower intracellular beta amyloid levels.

’However, we might need different drugs from the ones that we have, all of which are optimised to lower beta amyloid levels in the cerebrospinal fluid and interstitial fluid,’ says Gandy.

Phil Taylor

Enjoy this story? Spread the word using the ’tools’ menu on the left.

References

R Doody et al, Lancet, 2008, DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61074-0

No comments yet