How automatic structure elucidation could lead to more creative chemists

There is a certain moment when a chemistry student first sees an NMR machine which I think symbolises the point when they begin to cease being a student and start becoming a research scientist. In my case the moment came during an introductory tour of the analytical facilities at the University of Reading, UK. We final year students were warned not to get too close to the magnet with our bank cards, which seemed rather foreboding, and the technician started to explain roughly what the metallic cylinder did. There were words like ‘shimming’ and ‘resonance’, and I have to admit I found it all quite exhilarating, in a strange kind of way.

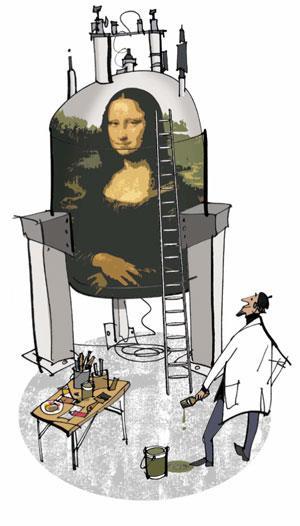

If he has his way, Craig Butts, director of NMR at the University of Bristol, UK, will eventually put a stop to all that. It’s not that he has an aversion to sentimental moments necessarily, but over the past four years he has been designing software that could eventually automate the process of structure elucidation by NMR.

Sounds ambitious? It is, and Butts says he is ‘completely of the view that this is not a problem which is 100% solvable’. Some compounds – benzene for example – have such deceptively simple NMR spectra that anyone, be they human or android, would struggle to interpret them accurately with no prior knowledge.

So how good is Butt’s software? He explains that the current prototype just needs a peak-picked spectrum as the input. Then you basically ‘just push go’ and out pops a structure that the machine computes based on pre-programmed rules of how to interpret the NMR data.

‘Now that structure may be the right one, or it may be complete chicken wire,’ says Butts. The software does get it right for reasonably complex molecules like menthol though, which sounds encouraging. Complicating factors like lots of quaternary carbons make some molecules harder than others, so Butts and his team are refining their algorithms right now, plus working to increase the types of spectra that the software can tolerate. Both of these improvements should make their software better at its job. They have also been studying how they might use nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (Noesy) data as an additional tool to verify inter-proton distances.

Those regular rounds of NMR training for new starters that chemistry departments run each autumn could soon be a lot shorter, then. It could be more a case of: ‘This is where you put your sample, and here’s the button you press’. And Butts thinks that might be a good thing: ‘I don’t think I should ever have to teach someone to shim a sample,’ he says. ‘Not because that’s not a useful thing to know – but simply because a computer can do shimming faster and better than a human being.’

But should we worry that, as the man who teaches students how to interpret NMR data for a living, Butts might be doing himself out of a job? ‘This comes up a lot,’ he says, ‘and I really don’t see it as a problem because I simply don’t believe that the software will ever be able to do the job as well as a chemist can. The point is that in many cases it may be able to do it faster.’

And surely he’s right. Synthetic chemists just want to know what that ‘stuff’ in their round bottomed flasks is; it is once they have that information that they can craft their next move in a synthesis or get a handle on what might have gone wrong.

‘Anything that simply involves following a set of rules, like counting numbers of protons and carbons; that can be done by a computer, better and faster than by a human,’ says Butts. So, in an ironic way, more automation in chemistry might actually lead to more creativity, not less. With the boring bits of NMR automated, chemists will have more time to dream up new ideas.

No comments yet