Todd Pagano helps to make research environments more inclusive to deaf and hard of hearing students

Todd Pagano didn’t know any sign language when he began teaching chemistry at the National Technical Institute for the Deaf (NTID). ‘It was sink or swim,’ he explains. An interpreter initially supported him in class and he received tutoring, but within a term or so he was ready to go it alone. ‘Like any language, you learn through immersion. The more you interact with both your colleagues and students, who are deaf and hard of hearing, the quicker you pick up the language,’ Pagano says.

He has always wanted to be a chemist. ‘Early on in elementary school, we had to draw a picture of what we wanted to do when we grew up and, apparently, I drew a scientist with beakers and whatnot,’ he explains. Upon arriving at university, he narrowed his career goal further to becoming a chemistry professor. With a laser-like focus, Pagano completed three degrees in chemistry along the path to obtaining a faculty position.

Coming home

NTID is a college at Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) in the US, and is the world’s largest technical college for deaf and hard of hearing students. Pagano was drawn to its faculty post advert for various reasons. The main purpose of the post – to build a new two-year associate degree programme – was highly appealing. He was excited about getting involved with a new culture and community. And Rochester is where he grew up. ‘It was a chance to come home,’ he explains.

The laboratory science technology programme has been running for over 20 years. Its primary objective is to prepare students for employment as laboratory technicians in industry. Graduate recruitment rates are pleasingly high, says Pagano, and a number of students choose to transfer to the RIT college of science to complete a biology and chemistry bachelor’s degree instead. ‘Some past students from this programme are now completing PhDs and one is now on our faculty,’ says Pagano. The proportion of deaf or hard of hearing science faculty at NTID is around half and is rising.

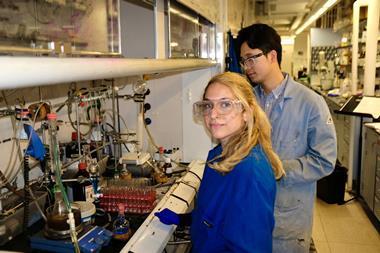

Pagano attributes the success of some of his associate degree students to early involvement in scientific research. Research projects teach transferable skills that employers value, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, teamwork and independence, he explains.

Pagano’s own research lab is primarily populated by undergraduate students who study dissolved organic materials in waterways. They develop new fluorescence spectroscopy-based analytical tools and, more recently, have started designing remediation strategies for reducing pollutant levels. ‘We’re looking at using adsorbent materials to take up pesticides or herbicides, for example, in waterways,’ he explains.

Cures and solutions

As part of the associate degree programme, Pagano added a course-based undergraduate research experience, better known as a Cure. These are an increasingly popular cure, pun intended, for US programmes that lack the capacity to offer a traditional research experience to every undergraduate. Students complete original research while in the teaching lab. ‘These Cure courses give students a flavour of what the research process is like,’ Pagano says. ‘The one that we’re running right now is looking at carbon nanotubes as a potential way to clean up waterways.’

Adaptations are fairly straightforward and almost always helpful to everyone in the environment

Recently, Pagano handed over the reins for the associate degree programme. He is now focused on expanding research opportunities for deaf and hard of hearing students at RIT. ‘I am advising other NTID faculty in chemistry and other disciplines on how to do Cure courses,’ he says. He is also working with faculty in other RIT colleges, and beyond, to encourage more traditional research opportunities for deaf and hard of hearing students.

Pagano describes the process of persuading academics and companies to work with deaf and hard of hearing scientists as having an activation barrier. Some people perceive communication challenges to be harder than they actually are, he says. There will sometimes need to be an interpreter or captionist for scientists who require them, but other than that the adaptations are fairly straightforward and almost always helpful to everyone in the environment. ‘Taking turns when speaking at group meetings – who couldn’t benefit from this? And keeping a clutter-free lab that allows more visual lines of sight is safer for everybody,’ he says.

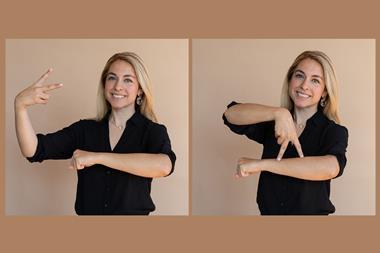

Pagano has seen the world of chemistry increasingly open up for NTID students. Efforts to create a standardised system of signs for chemistry, and other scientific disciplines, are gaining momentum – including the ASLCore project led by native signers, on which Pagano has collaborated. ‘It’s critical for student understanding to have appropriate signs that relay the context or meaning of terms, as well as follow the structure of American Sign Language,’ he explains. Pagano is also seeing an increasing number of employers willing to employ deaf and hard of hearing scientists, and more opportunities for his undergraduates to do research at other institutions as part of the US National Science Foundation’s summer research experience programme.

No comments yet