Amie Fornah Sankoh has persevered from failing primary school in Sierra Leone to gaining a biochemistry PhD in the US

Amie Fornah Sankoh, who grew up in Sierra Leone during the civil war and lost her hearing around three years old, is the first deaf, Black woman to receive a doctorate in any scientific, technical, engineering and maths discipline in the US, and possibly the world. She will graduate with a PhD from the University of Tennessee (UT) Knoxville’s Department of Biochemistry and Cellular and Molecular Biology on 20 May.

That’s a far cry from the 12-year-old girl who was failing elementary school in Sierra Leone because she couldn’t hear, and was sent to the US in the hopes that her deafness could be cured there.

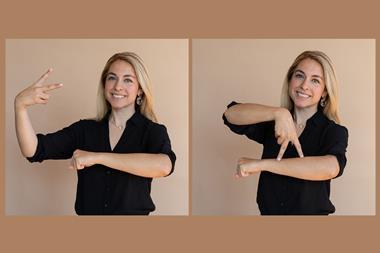

‘My father sent me to live with his best friend in America, who adopted me,’ she recalls. ‘Doctors in the US could not cure my deafness, but I was able to join the deaf community where I learned American Sign Language [ASL] over the next few years,’ Fornah continues.

But as a middle schooler in the US, she had continued to struggle and fail. It was not easy to learn a new language and keep up with her courses when she couldn’t didn’t know what her teachers or classmates were saying. Maths was the one area in which Fornah excelled. ‘Mathematics is just very visual, and I was able to enjoy that,’ she recounts. ‘Anytime a person talked, I didn’t understand anything, but when they would write out the formulas then I could see it and I could see each step of how to solve that problem.’

The attraction of chemistry

Her education really took off in high school, after learning ASL and being provided with an interpreter. ‘In high school, I really fell in love with the more complex mathematics, which is why I got into chemistry,’ she notes. ‘I was able to learn about and see chemical reactions – how the reactions occur – and then make predictions,’ she says. ‘It was very exciting – with the reaction, you’d have to write it down and draw it out.’

After high school, Fornah was working as a lab technician for Dow Chemical when she decided to pursue further education. She started with an associate degree in laboratory sciences from Rochester Institute of Technology’s National Technical Institute for the Deaf and then, with the support of a ‘wonderful undergrad mentor’, she says she continued and earned a bachelor’s in biochemistry there.

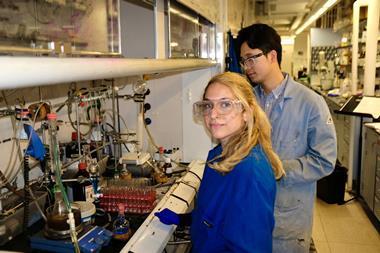

She worked in a lab following college graduation. ‘I was participating in research and enjoying it, and learning and experiencing the beauty of it, and then started to discover my own potential,’ Fornah explains. ‘And that led me to go ahead and enter the PhD programme at UT Knoxville.’

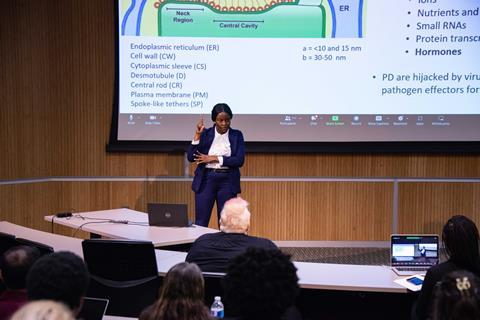

Fornah’s PhD research focused on the effects of hormones on plant-pathogen interactions. She obtained significant independent research support as a graduate student and is an author on four scientific publications so far.

Overcoming obstacles

One of the biggest obstacles that she has faced involves scientific communication. ‘Researchers love discussing science, they always are, and in the lab there’s communication and science happening every day, almost every minute,’ she says, noting that a lot of work has gone into helping her access, and participate in, such work interactions.

Traditional sign language doesn’t include specific scientific signs, so Fornah has had to rely on facial expressions and lip reading to both communicate and decipher research-related terminology. This means that the Covid-19 pandemic hit her particularly hard.

‘When Covid came, I remember my first thought was, “Oh, well, that’s it for graduate school for me” – communication was challenging enough, and then we had masks and Zoom was not friendly,’ Fornah recollects. ‘There were too many barriers for me.’ Over Zoom, for example, she had to bounce back and forth between the interpreter in one box and closed captioning in another box. ‘A lot of people didn’t realise that I listened with my eyes,’ she notes.

When her colleagues were masked during the pandemic, Fornah couldn’t read their facial expressions or lips. But her mentor was extremely supportive and worked to help minimise these roadblocks. For instance, Fornah and her coworkers wore see-through masks, and they made it a point to use written communication.

Leading the way

Sometimes Fornah wishes that there was at least one other person who looked like her, or was deaf like her, in the classrooms and labs during her PhD programme. But she is glad to have succeeded without such a role model. ‘I feel very, very proud for persisting,’ she says. ‘But I’m very happy that I am able to inspire the next generation of deaf scientists, so they can see their potential.’

It’s always easy to doubt yourself and give up, Fornah says. ‘I can’t tell you how many times I had self-doubt and thought I’m not able, I’m not going to pass,’ she tells Chemistry World. ‘The journey was very challenging, but with the right mentor I was able to overcome – I was able to focus on the science rather than on just advocating for my inclusion and accessibility.’

Her biological parents still live in Sierra Leone, but they have travelled to the US to watch her receive her PhD and prove what they already knew: that she could accomplish anything she wanted.

A postdoctoral position awaits Fornah at the Danforth Plant Science Center, a non-profit research institution in Missouri where she’s been carrying out her research since 2021, while she is searching for her next job. ‘Hopefully, I will continue research and continue to be involved in outreach with the deaf community and advocating on its behalf,’ she says.

But Fornah wants to uplift and empower everyone. ‘Maybe even able people themselves will be inspired, maybe they have doubt because graduate school is hard.’

No comments yet