In 2012, PhD researcher Rebecca Melen had a surprise waiting for her in the lab when she returned from her summer break. ‘I came back,’ she explains, ‘and my supervisor said “Rebecca, by the way, I’m sending you to Germany.” I was a bit shocked… I didn’t really speak the language!’ It was a key moment in Melen’s career, and one that has catapulted her on the fast track of academia as one of Europe’s up and coming researchers.

Graduating from the University of Cambridge, Melen had briefly explored a career in industry with Johnson Matthey, before returning to her alma mater to study main group catalysed dehydrocoupling reactions under the guidance of Dominic Wright. Winning a scholarship, she was lucky enough to be able to select her PhD supervisor (‘he had good group dynamics, got on with students and worked in the lab with students. I thought he’d be a good mentor’).

It turned out to be a life-changing decision. Wright sent her on a three-month placement to Ruprecht-Karls-Universität in Heidelberg, Germany, which gave her an eye-opening perspective. ‘I grew up a lot,’ she says. ‘I got to see how chemistry was done in another country. In the lab they all speak English, so that was fine. They tend to start a lot earlier – at 8am – in Germany, so initially I was the last person in the lab!’

International success

This first foray into international academia encouraged Melen to venture beyond Europe, taking a postdoc position with Doug Stephan at the University of Toronto, Canada. At first, she admits, she was nervous, but recommends others in academia embrace the experience. ‘Don’t be afraid,’ she counsels.

I grew up a lot getting to see how chemistry was done in another country

‘I was quite apprehensive about doing a postdoc abroad and applying for jobs, but it’s a very good opportunity. You’re only away for one or two years for a postdoc – if you don’t like it, you can always come back.’

While in Toronto, Melen had another surprise when she won the Royal Society of Chemistry’s Dalton Young Researchers Award 2013 for her work on main group chemistry. Again, it was her supervisors who had played a key role in her career. ‘This award is highly competitive,’ Melen says, ‘so when they nominated me it was a really good surprise. Some students feel they’re not confident or good enough, but their supervisors should encourage them.’

The award opened up a world of possibility. Melen attended the 63rd Nobel laureate meeting on chemistry, Lindau, Germany, where she was able to interview Nobel prize winner Robert Grubbs and found herself named as one of the ‘30 [scientists] under 30’ by Scientific American. ‘The meeting was brilliant,’ she recalls. ‘It’s just Nobel laureates and junior academics … you get to sit with them at dinner, talk with them, dance with them.’

Groups and main groups

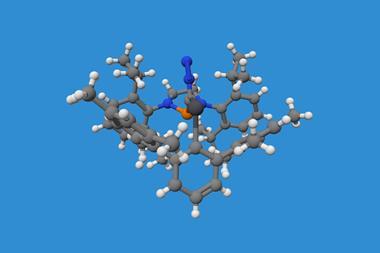

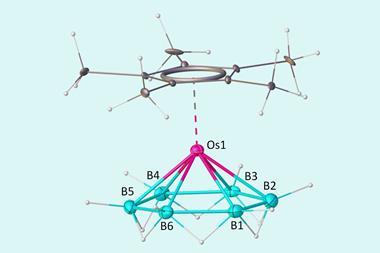

Returning to Heidelberg, Melen continued her success streak, winning the European Young Researcher Award in 2014, before taking a step up in academia when she joined Cardiff University as a lecturer in inorganic chemistry, forming a research group focused on frustrated Lewis pairs and main group catalysis.

‘It was a big step,’ she reflects. ‘It’s different from postdoc where you’re just doing research and writing papers – you’re moving in to academia. The biggest challenge for me was time management, because I’ve got to do the research – I still try and get into lab and work with the students, get them going on projects – but I’ve also got to write grants and papers, and do teaching on the side.’

This may not seem to make much time for anything else, but Melen has taken a unique approach to the problem by appointing her horse, Indium, as an honorary member of the group. ‘I like to go horse riding; as soon as I moved to Cardiff I bought a horse before I found accommodation,’ she confesses.

Melen has also continued to rack up further awards, the latest being the 2016 Clara Immerwahr Award for young scientists in catalysis research, with a grant to work at the UniCat catalysis research cluster in Berlin.

And, even with her success, Melen remembers the spark that her own supervisor provided, and looks to pass it on to the next cohort of chemists. ‘At the moment I have quite a small group,’ she says. ‘I’d like to get more students and postdocs – and do more good science.’

No comments yet