UK helps Afghanistan assess its mineral wealth

Armed with a few rudimentary fume cupboards, a small spectrophotometer and a handful of simple chemicals, scientists from the British Geological Survey have started the long process of rebuilding the analytical geochemistry capability of a country that for decades has been riven by war.

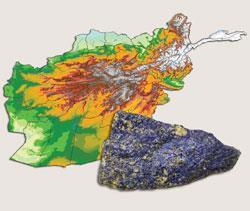

For most of us Afghanistan is a distant, rugged country defined by a turbulent and often violent recent history. But despite its past and current difficulties, Afghanistan is gradually being rebuilt. An important part of this reconstruction is to enable the Afghan population to make the most of the country’s mineral wealth.

Afghanistan’s natural resources include significant deposits of metals such as gold, silver, copper and zinc; precious and semi-precious stones including lapis, emerald and azure; and coal, natural gas and oil.

Accurate geological surveys of the country’s mineral resources are key to locating deposits and advising potential investors, and for this reason the Afghanistan Geological Survey (AGS) is being revitalised after decades of decay and neglect. Geological surveys from the UK, US, Japan and the Czech Republic are helping to rebuild the AGS. The UK’s contribution is a three-year project, which finishes this September, funded by the Department for International Development, for the British Geological Survey (BGS) to provide training and equipment to get the AGS back on its feet.

The challenge has been significant. The AGS headquarters in Kabul, for example, has had to be reconstructed almost from scratch, as Jack Medlin of the US Geological Survey explains: ’The AGS building is very large, but when we arrived in 2004 it was essentially a shell. There were no windows, no doors, no furniture, no wiring, no plumbing and the building had been bombed and looted of everything.’ It took six million dollars and two years work to make the building habitable.

Michael Watts, an analytical chemist with the BGS, is deputy leader of the BGS project whose aim is to get the AGS laboratories up and running. Five laboratories have so far been established: a sample preparation lab which is largely devoted to crushing and grinding rock material; an industrial mineral lab for testing the physical properties of minerals; a thin-section lab for producing samples for examination under the microscope; a petrographic lab for classifying and characterising rock samples; and a gem analysis lab. The chemistry lab will be shipped out this summer.

This laboratory will be, at least initially, rudimentary. ’We have to take a very pragmatic, low-tech approach,’ Watts says. ’We are establishing a very basic infrastructure with a water and power supply, some simple fume cupboards and we will set up some simple assays to assess the staff’s practical skills and chemical knowledge to recommend future training programmes.’

The main piece of equipment for the laboratory will be a portable Palintest spectrophotometer. Watts explains, ’The idea is initially to teach the staff how to use the equipment to test water for the presence of zinc, nickel and copper. A water sample is filtered and placed in the machine, which reads the absorbance wavelength and subsequent concentration of the particular metal. This information can provide an indication of the presence of minerals upstream from where the sample was collected, for example. We’ve also developed a way of analysing soils and rock materials for copper, where hydrochloric acid is added to the sample, it is heated, and a buffer and organic complexing agent is added. This can also be measured in the photometer.’

Around 85 people work in the AGS laboratories, with 10 or 15 in the chemical analysis lab. Levels of expertise among the staff are highly variable. ’Some of the personnel have graduated from universities in the old Soviet Union, others from the university in Kabul and the range of education varies a lot,’ Watts says. ’Some of the younger graduates from Kabul do not have a high basic level of knowledge, although they are very keen. We were expecting a higher level of knowledge across the board, but we found we are having to go right back to basics, particularly with fundamental IT and language skills.’

If the AGS can start to function efficiently once again, the future is potentially bright. Significant donors such as the World Bank are waiting in the wings with substantial investment. ’It is important that we do not try to do too much too quickly,’ Watts points out. ’There would be little point in kitting out the laboratory with, say, atomic absorption spectrometry, as in the current climate such a machine would be difficult to run and maintain. Companies that supply equipment will not go out to Afghanistan to repair or maintain instruments. In the future the AGS will need to develop contacts with neighbouring countries such as India and Pakistan to obtain support and to get access to chemicals as these are difficult to ship from Europe. We can’t be too ambitious at this stage - it would not be fair on the Afghan staff.’

Simon Hadlington

No comments yet