Artificial dental enamel could soon be on its way to your mouth.

Artificial dental enamel could soon be on its way to your mouth, say chemists.

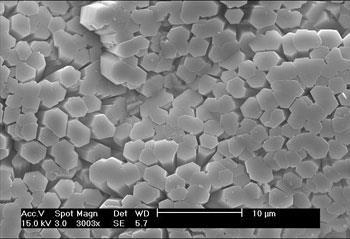

Enamel forms the outermost layer of your teeth and is the hardest mineralised tissue in the body. It is made of rod-shaped crystals of hydroxyapatite, a calcium phosphate mineral, arranged into a prism formation.

Brian Clarkson of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, US, and his team has managed to grow crystalline fluoroapatite with a structure very similar to human dental enamel. This tightly-aligned crystal structure was formed in water under very high pressures, at temperatures between 200 and 600?C. The work was published this month in the journal Advanced Materials.

This is the first time that a material with the same structure as dental enamel has been made without the use of protein or ameloblasts, the enamel-forming cells in the gums. Previous attempts to make artificial enamel have been thwarted because the prism structure of human enamel is extremely difficult to mimic, but the hydrothermal approach appears to have been the key to success.

Ameloblast cells die once a tooth has formed, so any damage to the enamel cannot be repaired by the body. Artificial enamel could provide a better alternative to current materials used for dental treatments, such as metal fillings and porcelain caps, the scientists say.

’This synthetic enamel has the same composition and structure as natural enamel so it will wear at a similar rate to natural enamel and not cause the differential wear problems which can occur when porcelain grinds away the natural enamel during chewing,’ Clarkson told Chemistry World. Since the synthetic enamel has high fluoride content, it should also be more resistant to tooth decay, he added.

Making the artificial enamel stick to teeth could still pose a major hurdle, cautioned Trevor Burke of the University of Birmingham, UK, who works with composite resins that are modern replacements for porcelain caps. ’But resin technology has improved immeasurably over the last 30 years,’ he said, ’and being able to grow and use human enamel would be of great interest to the field if we could bond them to the teeth.’

Victoria Gill

References

et alAdv. Mater, 2006, 18,1846

No comments yet