Technique can produce high-performance, flexible capacitors using a simple fabrication process

Producing a highly sought wonder material can be as easy as burning a DVD. That is according to chemists in the US, who have used a standard DVD player to reduce films of graphite oxide to graphene. These graphene films can be made into high-performance, flexible capacitors fit for bendy solar cells or roll-up displays.

A lot of current research is focused on producing high-performance capacitors for energy storage. Electrochemical capacitors, otherwise known as supercapacitors, have some promising attributes - they can undergo frequent charge and discharge cycles, for instance - but in general they are still limited by low energy and power densities. Higher energy densities would enable devices to run longer, while higher power densities would enable them to run faster.

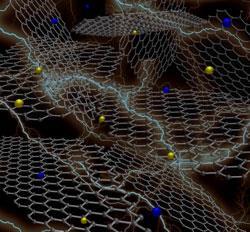

Graphene - the subject of the 2010 physics Nobel prize - is one material that could improve the performance of electrochemical capacitors. A sheet of graphite just one atom thick, it has an extremely high surface area and electrical conductivity, which suggests it would offer high energy and power densities. Unfortunately, graphene has proved difficult to fabricate and samples that are produced often stick together, reducing their surface area.

Maher El-Kady and others at the University of California at Los Angeles have now found a way to fabricate graphene films, and graphene capacitors, without any sticking together. The researchers take a DVD and apply a layer of plastic, followed by a film of graphite oxide. They then insert the DVD into a standard DVD drive, so that the in-built laser chemically reduces the graphite oxide to graphene. Having removed the disc, the researchers peel off the plastic, which is then coated in graphene, and cut it into whatever shapes they desire.

To make the graphene films into capacitors, El-Kady’s group fill the space between two parallel sheets of the laser-scribed graphene with an electrolyte, phosphoric acid. Not only are these capacitors flexible, but they have an electrical performance that surpasses other commercial energy-storage devices, according to the researchers’ tests. Compared with a carbon electrochemical capacitor, for instance, the graphene capacitors had energy densities that were twice as high and power densities that were 20 times higher.

’We believe that our devices will pave the way to further applications - for example, flexible power supplies for roll-up computer displays, wearable electronics, and energy-storage systems to be combined with flexible photovoltaic cells,’ says El-Kady.

Yury Gogotsi, a materials scientist at Drexel University in Philadelphia, US, is impressed by the fabrication technique. ’[The] two main points that are most novel ... are not particularly the high gravimetric capacitance and energy density of the devices, but the simple fabrication process and exceptional mechanical stability, which has not been previously reported anywhere else,’ he says.

El-Kady says the next step is to demonstrate that the fabrication volume can be improved, while minimising cost. ’Our initial calculations show that the price of the precursor, graphite oxide, and the whole process is viable for commercial applications,’ he adds.

Jon Cartwright

References

M El-Kady et al, Science, 2012, 335, 1326 (DOI: 10.1126/science.1216744)

No comments yet