A new textile produced by US researchers from polyethylene – the simplest and cheapest of all polymers – shows superior cooling properties to cotton or linen, is more stain resistant than polyester, is easily recyclable and can potentially be made from recycled materials. The researchers believe it could, therefore, contribute significantly both to cut the ecological footprint of the fashion industry and reduce the world’s plastic waste mountain.

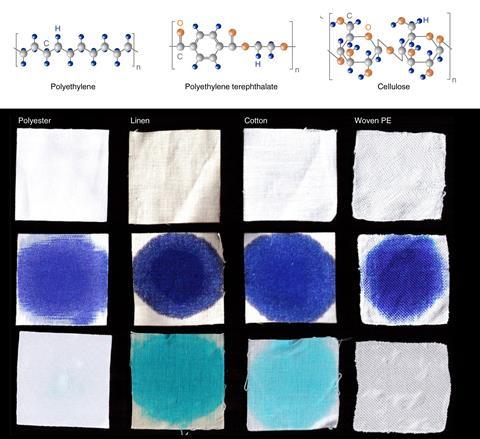

The textile industry has a huge carbon footprint with the 56 million tonnes of fabrics it produces every year responsible for 5–10% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. The industry once depended entirely on natural fibres such as cotton, linen and wool, but in the past century synthetic polymers such as polyester and nylon have become increasingly widespread. Polyethylene, however, has been largely overlooked. ‘There are a couple of serious impediments,’ explains materials engineer Svetlana Boriskina at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ‘One is that it’s hydrophobic – it’s used as protection against rain and in applications where you want to stop moisture from coming through, but it’s hugely uncomfortable if sweat gets trapped under clothes.’ Partly because of this, it is impossible to dye polyethylene using traditional techniques.

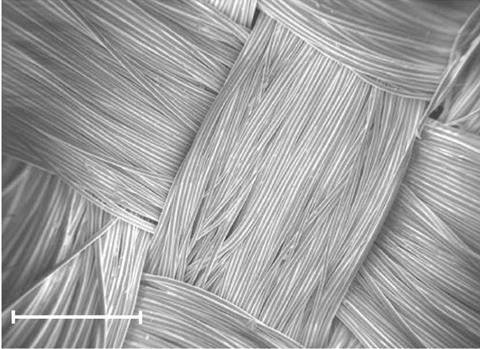

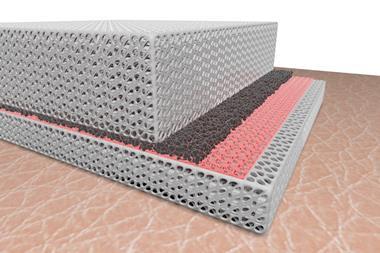

In the new research, however, Boriskina and colleagues discovered that the hydrophobicity can be mitigated simply by melt-spinning the polymer into micrometre-diameter fibres. This partially oxidises the surface, making it barely hydrophilic. ‘It’s just enough to make it wick water through by capillary force, but the interior of the fibre is still deeply hydrophobic,’ explains Boroskina. ‘Water cannot go in, so it has nowhere to go but to evaporate.’ Textiles woven from the fibres can therefore behave like advanced, multi-layer sports synthetic fabrics. Crucially, however, as they contain only one polymer, they can recycled much more easily.

Moreover, the structural simplicity of polyethylene gives the textiles much higher infrared transparency than fabrics woven from more complex polymers, allowing for better radiative cooling. ‘Polymers that are more complex have additional oxygen atoms and nitrogen atoms, for example, and different combinations of how these atoms are bonded,’ explains Boriskina. ‘The more combinations you have, the more vibrational modes. These cover the whole spectrum, and everything is absorbed. With polyethylene, it’s pretty much carbon–carbon bonds and carbon–hydrogen bonds … there’s this big vibrational window where there are no modes, and that happens to be around 10 microns where the human body emits.’

The dyeing issue may no longer pose a problem either. Boroskina says that, where possible, the textile industry is increasingly moving away from the traditional wet-dyeing process, which is ‘to put the textile or yarn in usually-toxic dye, wash it multiple times to remove excess dye and wash all that out into the wastewater, which creates a real risk to the environment’. Instead, colourants are incorporated into molten materials before they are spun into fibres. The dye-resistance of the fibres even had the advantage of making their textile more stain-resistant than cotton, linen or polyester, allowing it to be washed more economically at lower temperatures.

The team is now working with the polymer – which could be produced from recycled polyethylene – with a view towards commercialisation. ‘Honestly, I think it should become the material of choice for the textile industry, but of course I’m very biased, so we’ll see what happens,’ she says.

Po-Chun Hsu of Duke University, US, who was not involved in the research, says he particularly admires its ‘different and more objective view of polyethylene as a fabric material’. ‘People have a very rigid view of polyethylene, mainly because of plastic bags and microplastics in the ocean, and we should definitely do something to mitigate those,’ he says. ‘But if we compare which one is more sustainable it’s always a good idea to look at the entire process from cradle-to-cradle if you recycle those and, from their research, it appears that polyethylene is not as bad as people thought.’

1 Reader's comment