New method offers a rapid, robust way to make protein microarrays

A new method to rapidly generate protein microarrays has been developed by UK researchers at the University of Manchester. Offering a fast, efficient and user-friendly route to immobilised functional proteins, it avoids the need for laborious protein purification or chemical tagging.

Protein microarrays - thousands of functional proteins immobilised on a plate no bigger than a standard envelope - are used in various applications, from biosensing to industrial catalysis. However, the speed at which these plates are manufactured is often slow and techniques are constantly being sought after to improve efficiency and lower costs.

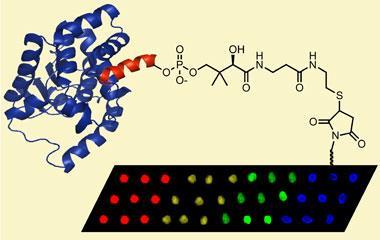

Jason Micklefield and colleagues have now developed a new way to attach proteins to the plate, using direct enzyme catalysis - taking an existing, mild synthetic strategy from solution and applying it to a functional surface. In practice, three ingredients are essential: an active enzyme; a functionalised surface; and a supply of tagged protein of the scientist’s choosing. With all three in place, the reaction to attach the tagged protein to the surface is complete in just a few hours.

’In our opinion, this is the best way of immobilising proteins for the development of microarrays,’ says Micklefield, who demonstrated the method’s versatility by successfully immobilising four functional proteins. ’If protein arrays are to become as widely used as DNA arrays then you need to be able to generate them in a fast, high-throughput fashion.’

Protein friendly

The researchers claim that this new technology surpasses existing methods and highlight two key advantages. Firstly, the critical tag fused to each protein is small, only 11 amino acids in length, and considerably less intrusive than alternatives such as protein capture, which uses a bulky second protein to attach the protein of interest to the surface. As a result, the likelihood of disruption to the protein’s folding - or its function - is greatly reduced.

Secondly, the site-selective immobilisation can be carried out from the crude protein sample (lysate), in a single step, bypassing purification and additional chemical modifications. This advance not only saves time, but minimises loses of the precious protein material, say the researchers.

’This is the first attachment method of its kind. It’s very nice because it creates stable, covalent bonds under mild, protein-friendly conditions,’ says Brian Haab, a biomedical scientist at the Van Andel Research Institute, US. ’Those features could be useful in a variety of applications, such as bio-compatible materials generation.’

The researchers are quick to concede that as it stands their demonstration is a far cry from a viable protein microarray. However, they stress that by combining their method with mechanical spotting techniques, arrays with large numbers of proteins could readily be manufactured. With this in mind, they add, a number of industrial groups have already expressed an interest in the technology.

Fred Campbell

Enjoy this story? Spread the word using the ’tools’ menu on the left.

References

etal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, DOI: 10.1021/ja8030278

No comments yet