US chemists have devised a molecular mimic of an enzyme that destroys toxic alkyl mercury pollutants

US chemists have devised a molecular mimic for an enzyme that destroys toxic alkyl mercury pollutants. Jonathan Melnick and Gerard Parkin of Columbia University, New York, report that their model provides an insight into how this deadly toxin can be destroyed.

Many tonnes of ionic mercury, which is readily converted to alkyl mercury, have been produced as a result of coal-burning. The best-known example of human exposure occurred in Minamata, Japan, in the 1950s, when a chemical plant released ionic mercury into a nearby lake. Methyl mercury accumulated in the fish resulting in the deaths of nearly 1800 local people.

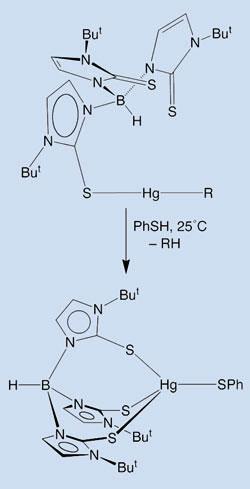

But some bacteria can survive in such contaminated waters thanks to the enzyme MerB, which breaks the otherwise very stable Hg-C bond. The mechanism of MerB was not well understood, but it was known to rely on four sulfur-containing cysteine amino acids for its activity. The Columbia team took this as a starting point, and chose a ligand for mercury that could recreate the sulfur-rich environment of the active site.

Melnick and Parkin, whose data are published in the journal Science, were able to observe complexes where alkyl mercury formed different numbers of Hg-S bonds with the ligand. The complexes reacted with a second thiol compound and broke the Hg-C bond. The researchers also showed that complexes with two Hg-S bonds are more active in this reaction than those with only one. The results constitute ’the first well-defined demonstrations that Hg-C bond cleavage by a S-H group is modulated by coordination number,’ Parkin said.

Engineering a substance that could devour alkylmercury in polluted areas is the long-term goal for research in this area. ’We’re a long, long way from that,’ conceded Parkin, ’but we’ve shown that with the right ligand environment you can get the mercury-alkyl bond to cleave. And you can do it in a nice small-molecule system,’ he said. Parkin is now working to determine how the nature of the ligand influences the susceptibility to cleavage of the Hg-C bond.

Vital for environmental clean up

James Omichinski of the Universit? de Montr?al, Canada, believes understanding the mechanism at this level is vital for development of efficient methods to deal with alkyl mercury. There is an opportunity, he said, to put technology of this type to use in treatment of effluent from factories, particularly in the vaccine industry which produces alkylmercury bi-products. ’People are trying to design bioreactors with MerB to clean this up prior to release into the environment. This is a case where a synthetic enzyme could be used’ he told Chemistry World.

Tom Westgate

Enjoy this story? Spread the word using the ’tools’ menu on the left.

References

Science317, 225

No comments yet