The effects of drinking excessive amounts of alcohol are well known. In the short-term, alcohol leads to feeling drunk followed by a hangover, while regularly consuming more than the recommended amount of alcohol can cause liver disease, heart disease, stroke and cancer.

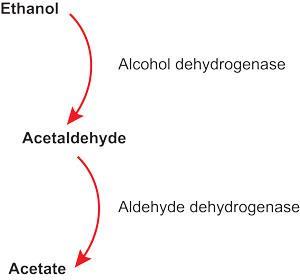

Some of the adverse effects of alcohol are thought to be caused, not by the ethanol itself, but by ethanol’s first metabolite, acetaldehyde. Ethanol is metabolised into acetaldehyde by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and then into acetate by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). Unlike acetaldehyde, acetate is innocuous and may even be responsible for some of the positive health benefits of alcohol consumption. Therefore the key to reducing alcohol-related damage lies in minimising the amount of time acetaldehyde is present in the body.

Hua-Bin Li and co-workers from Sun Yat-Sen University in Guangzhou hypothesised that substances which alter the activities of ADH and ALDH would consequently alter the duration acetaldehyde exposure. They went on to systematically test the effect a variety of common carbonated beverages and herbal teas had on ADH and ALDH activity assays.

Some of the drinks tested, including a herbal infusion known as Huo ma ren, were found to increase the activity of ADH, thus accelerating the metabolism of ethanol into toxic acetaldehyde, whilst also inhibiting ALDH, reducing acetaldehyde removal. Consuming these drinks after drinking alcohol might therefore increase exposure to acetaldehyde and promote alcohol-related symptoms.

In contrast, some of the drinks markedly increased ALDH activity, thus promoting the rapid break-down of acetaldehyde and could minimise the harmful effects of drinking alcohol. Among these drinks were Xue bi and Hui yi su da shui, carbonated drinks known in English as Sprite and soda water, respectively.

Edzard Ernst, a leading expert in medicinal science from the University of Exeter in the UK describes the work as interesting. ‘These results are a reminder that herbal and other supplements can have pharmacological activities that can both harm and benefit our health.’ However, Ernst is cautious and stresses that independent replications are necessary before we fully accept the results.

Li and colleagues are now looking to see if their in vitro findings translate into in vivo results.

No comments yet