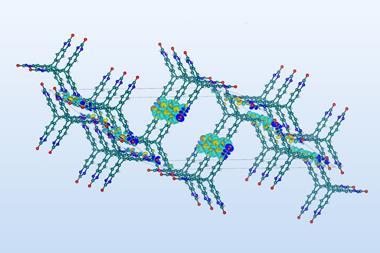

Crystals made from mucic acid are the stiffest organic crystals reported to date.1 They owe their rigidity to a dense web of hydrogen bonding between their molecules, giving them mechanical properties comparable to metals.

Crystals are often thought of as brittle, but this is not always true. Organic crystals, which are made of small molecules held together by intermolecular interactions, can be mechanically compliant because these interactions can compensate under stress. These relatively weak interactions usually limit how rigid the crystals can be. Occasionally, though, organic crystals can be exceptionally stiff – a possibility that prompted Panče Naumov at New York University Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates and colleagues to explore the upper limits of this property in such materials.

Many potential candidates for stiff organic crystals are well known and widely available. While their physical properties have may been studied, their mechanical properties were often overlooked. With no reliable computational methods to predict rigid molecular crystals ‘these are extremely difficult to find’ says Naumov, ‘at the moment it is not possible to systematically search for them’.

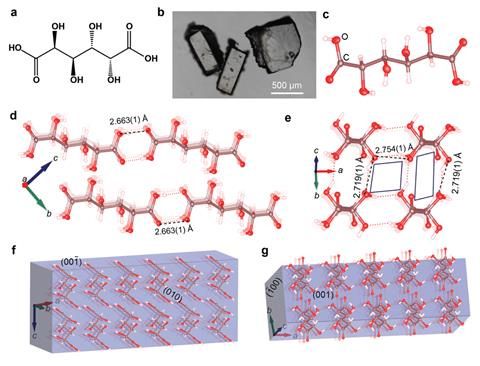

The team therefore relied on their chemical intuition and experience to identify a suitable candidate, looking for indicators such as high density and the ability to form plenty of intermolecular interactions. Mucic acid, also known as galactaric acid, is a compound long used in various applications – and it ticked both boxes, combining unusually high density with a multitude of carboxylic acid and hydroxyl groups, enabling extensive hydrogen bonding.

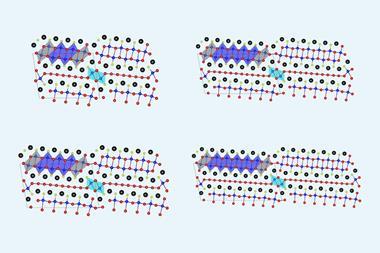

Stiffness, put simply, is how much a material resists elastic deformation and is measured experimentally using Young’s modulus. To determine this, researchers often use a technique called nanoindentation. In a previous study,2 the team found that most organic crystals have a Young’s modulus between 10 and 25GPa, with only about 8% of the categorised compounds exceeding 25GPa and deemed extraordinarily stiff. In their new study, the team measured the Young’s modulus on the (100)/(100) faces of the mucic acid crystal to be around 50GPa, making it the stiffest organic crystal reported to date. Computational analysis supported this finding and predicted an even higher value of 68.5GPa. Other accessible faces of the crystal had a Young’s moduli near 30GPa – still among the highest ever recorded.

The team describe these mucic acid crystals as ‘ultrastiff’ due to their unprecedented stiffness, which is comparable to some metals and inorganic materials. For example, aluminium has a Young’s modulus of around 70GPa.

The team also examined the crystals’ hardness, ie their ability to resist pressure from a sharp object. They found that mucic acid crystals combine high hardness with exceptional stiffness. Together with their high density, these properties create a mechanically robust yet lightweight organic crystal. Marijana Đaković, an expert in crystallography and crystal engineering from the University of Zagreb in Croatia, says ‘this favourable constellation of properties is achieved within a single crystalline system, whereas previously known ultrastiff crystals typically excelled in only one or two mechanical parameters.’

The mechanical properties of mucic acid crystals result from both an abundance of intermolecular interactions and the way the molecules pack together to form a dense network of relatively strong hydrogen bonds. Đaković notes that the mucic acid crystals ‘highlight how strategically organised hydrogen-bonding networks can override molecular flexibility and endow a crystal with extraordinary stiffness and mechanical resilience.’

Organic crystals are typically lightweight and biodegradable, advantages not echoed in their inorganic competitors. As a result, organic crystals could become attractive alternatives for a range of applications. ‘The concept presented paves the way for integrating organic crystals into technologies that demand high mechanical robustness coupled with minimal weight,’ adds Đaković.

References

1 D P Karothu et al, Chem. Sci., 2026, DOI: 10.1039/d5sc05888k

2 D P Karothu et al, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2022, 61, e202113988 (DOI: 10.1002/anie.202113988)

Additional information

No comments yet