Interference between morphine and norepinephrine imaged in real time

Medicines that use a combination of several drugs can sometimes produce unexpected effects in patients. Now, a team of scientists think they have figured out how that can happen.

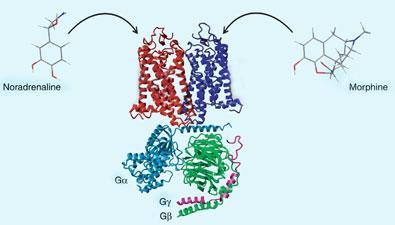

They have shown for the first time how G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) - a family of cell surface receptor proteins that are the target of around half of all drugs - respond differently to signalling molecules or drugs when they couple together.

Different GPCRs often pair up with each other as dimers in the body, but most previous research has focused on the properties of lone receptors.

To investigate how combination effects arise, the team looked at two molecules that work by activating GPCRs - the painkiller morphine and norepinephrine (NE), a signalling molecule that triggers the body’s ’fight or flight’ response in stressful situations. Both morphine and norepinephrine normally bind to and activate their receptors. But when cells are exposed to both chemicals together, they respond unexpectedly - morphine’s effects persist while those of norepinephrine are suppressed.

The team attached two fluorophores to different parts of the norepinephrine receptor. In the inactive receptor, the two fluorophores are close together and look yellow when illuminated by light.

But when the receptor is activated, it changes shape. As a result, the fluorophores glow blue because they are further apart and no longer interact.

’Using this tool, I was able to visualise the activity of the receptor in a live cell in real time,’ Jean-Pierre Vilardaga of Harvard Medical School, Boston, US, told Chemistry World.

When they exposed pairs of morphine and norepinephrine receptors to both chemicals simultaneously, the team saw that the norepinephrine receptor remained inactive - suggesting that it was somehow being switched off by the neighbouring active morphine receptor.

’We found that there is a direct cross-talk between one cell surface receptor and another,’ Vilardaga said.

Drug development

The finding neatly explains why norepinephrine has no effect on cells when they’re exposed to it at the same time as morphine. Vilardaga believes the findings could also be relevant to the treatment of Parkinson’s disease, which involves another pair of GPCRs.

Jean-Philippe Pin of the Institute of Functional Genomics at the University of Montpellier, France, who also works on GPCRs, said, ’My feeling is that [these results] will be general to GPCR dimers and could help the development of drugs that are more specific.’

Ananyo Bhattacharya

References

et al.Nat. Chem. Biol., 2008, DOI: 10.1038/nchembio.64

No comments yet