Chemistry came alive in a reimagined form at the 75th Yusuf Hamied Chemistry Camp for Visually Challenged Students, hosted at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Bombay.

Whether it’s the vibrant red and green flames of strontium and barium salts during a flame test or the striking ‘golden rain’ formed by the reaction between lead nitrate and potassium iodide, the visual drama of chemical reactions is often what captivates students. The very spectacle that makes chemistry so appealing can also become a significant barrier, shutting visually impaired students out of the full experience while leaving educators grappling with how to make the subject accessible to everyone.

Guided by the belief that chemistry is for everyone, this inclusive education project set out to go beyond the usual high school chemistry experiments. The team redesigned the experiments to engage touch, smell and sound. The result was a rich, multi-sensory experience that allowed 59 visually impaired students from schools in Mumbai, Nasik, Pune and Solapur to explore the wonders of chemistry.

The initiative was supported by the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) and funded by Yusuf Hamied, chairman of Cipla.

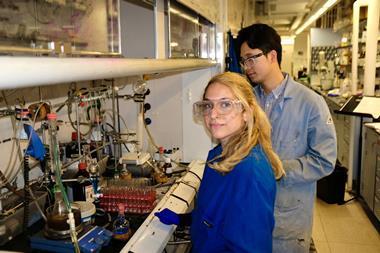

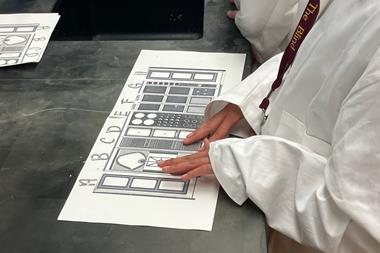

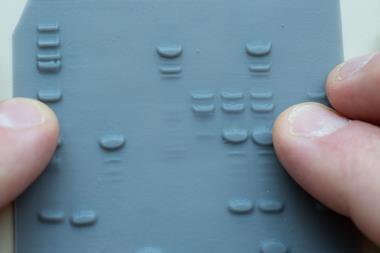

The camp introduced a new handbook featuring six hands-on experiments developed by Chandramouli Subramanian of IIT Bombay, which were translated into braille. Students were divided into small groups, and each experiment was run by a volunteer from the institute, enabling the students to carry out the activities independently.

‘Science must be accessible to all,’ said Swetavalli Raghavan, head of innovation strategy and government affairs at the RSC. ‘This initiative helps break the myth that chemistry is a visual science. With the right tools and teaching methods, we can open up the world of scientific inquiry to every learner, regardless of ability.’

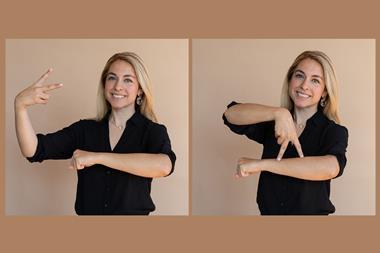

When light becomes sound

Tactile chemistry kits, featuring textured materials, raised diagrams and braille labels, have helped make science more accessible for students with visual impairments. But Subramaniam pointed out that these kits can be costly for schools. Therefore, his team focused on adapting experiments usually included in the school curriculum.

A school science fair classic, the potato battery experiment shows how a vegetable can power a small electronic device. By inserting two different metals, typically zinc and copper, into a potato, students create a simple electrochemical cell that generates a small voltage that can power low-energy devices, such as LEDs. The team simply replaced the LED with a buzzer.

In designing the activity, the team also aimed to give students a broader understanding of energy conversion. As Subramaniam explained, the experiment became a starting point for a larger conversation – tracing how plants absorb solar energy through photosynthesis, store it as chemical energy in the form of sugars, and how that same energy, now held in a potato or lemon, can be released and transformed into sound through a simple electrochemical reaction.

Experiments involving heat were handled with extra care. These included an esterification, where a carboxylic acid and an alcohol reacted in the presence of an acid catalyst to yield a fruity-scented ester when heated in an oil bath. Unlike other activities where students did most of the work themselves this step required hands-on support from the volunteers.

In addition to pre-measuring the chemicals and carefully supervising each step. ‘One great thing that [the] professor suggested was to put on blindfolds and do your experiments one or two times, so that you’re sensitised to their experiences,’ says Devashish Bhave, a volunteer at the camp. ‘We even tried each other’s experiments with blindfolds on to check if our instructions were clear enough.’ He highlighted that this exercise was a powerful reminder that what might seem simple or obvious with sight becomes much more complex without it.

‘Doing the experiment 72 times might sound repetitive, even boring, but it was one of the best experiences I’ve had in a lab,’ adds Devashish. ‘Each time a student dropped Mentos into the [fizzy drink] bottle and sealed it with the balloon-fitted cap, the balloon began to expand as gas was released. I would ask them to feel the balloon becoming bigger. The joy and excitement that they had on their faces made every single time worth it.’

In conversations with volunteers, several students shared that they had arrived at the camp feeling hesitant, even afraid of the lab, due to past experiences. However, by the end, they felt hopeful about pursuing a career in science.

‘We have chemistry as a subject in school, but the experiments in the syllabus were always taught verbally, we never had the chance to do them ourselves,’ says Saee, one of the workshop participants. ‘This was the first time I experienced chemistry hands-on, and it gave me the confidence to know I’m capable of doing these experiments. Now, I’m excited to explore even more.’

No comments yet