Clare E Wilkes

Book Guild Publishing

2019 | 339pp | £9.99

ISBN 9781912575473

Colonel Brian Duncan Shaw (1898–1999) was a very special character who believed and showed that chemistry is a serious subject but should also be fun. This book is an enchanting memoir of him.

As a schoolboy, Shaw loved making and using gunpowder. He never lost his interest in explosives – his career in two world wars must have encouraged this. On his 18th birthday, he enlisted in the Sherwood Foresters’ Regiment and experienced trench warfare at the Somme. He was awarded the Military Medal for rescuing a wounded soldier under fire. In 1919, he went on to study chemistry at University College Nottingham (now the University of Nottingham), where he got a first. After his PhD studies with Frederic Kipping, Shaw became a lecturer at the university in 1924.

Fifteen years later, he enlisted again in the Foresters’ as part of the British Expeditionary Force. When the Force was evacuated at Dunkirk, Shaw’s battalion formed the rearguard, which had to remain in Germany. It became fragmented, and Shaw briefly joined the Free French but was arrested by the Germans in late 1940. As a supporter of the Free French, he could well have been shot and was fortunate to have been made a prisoner of war instead.

He returned to Nottingham in 1946, retiring in 1965. In addition to his considerable teaching duties, Shaw continued to give his demonstration lecture titled simply ‘Explosives’, which by then was internationally famous. He gave it over 1500 times, in British universities, the Royal Institution, many schools, Women’s Institutes, military and atomic energy establishments, and overseas – from Rome to San Francisco. These unforgettable lectures were impeccably timed, conveying much chemical information while holding his rapt audiences in thrall. In 1973, the Home Office’s inspector of explosives unsuccessfully tried to ban his lecture on safety grounds.

I attended two of these lectures at Imperial College London, UK. Despite being held in the largest theatre, both were packed. Typically, Shaw started by heating several sealed capsules of water, which would explode loudly and unexpectedly at unpredictable times. Several gunpowder explosions followed, then gas explosions aplenty of oxygen mixed with hydrogen and other gases. He would explode potassium chlorate–phosphorus mixtures and start fires of phosphorus in oxygen.

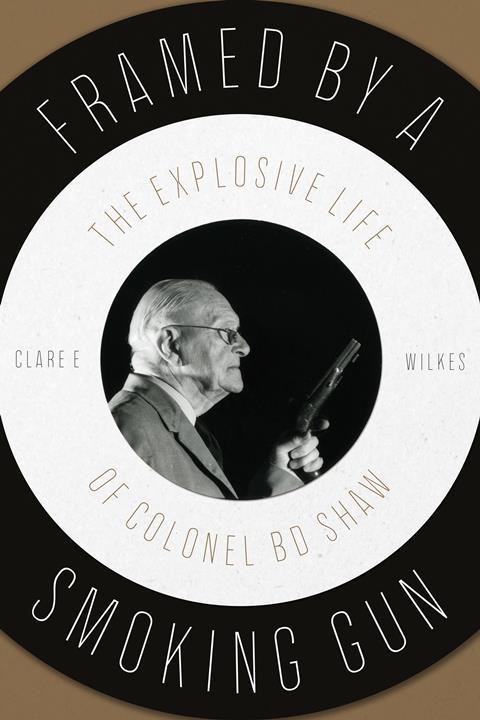

A favourite was the nitric oxide–carbon disulfide reaction in a long glass tube: on ignition, a blue flame would rush down the tube and the typical ‘breathing dog’ sound, diminishing in pitch but not intensity, rang out. He would use an 1857 four foot muzzle-loading musket to fire a tallow candle into an assembly of wood panels and bricks, simulating a barn door, piercing them all. The lecture always ended with the simultaneous firing of two first world war pistols while he recited part of the final verses of Hamlet.

Framed by a Smoking Gun is a joy to read, clearly written and fully referenced with an excellent index, and at a very reasonable price.

No comments yet