The scientists using visual storytelling to communicate their work – and how you can do it too

Writing her PhD thesis brought a sudden and upsetting realisation to Veronica Berns. Many of the people she wanted to share her research with wouldn’t be able to understand it. Her thesis focused on how solid materials pack together at the atomic level, a phenomenon that is difficult to predict. PhD theses like these can be uninviting and exclusionary to non-scientists and ‘while scientifically accurate, [they don’t] capture the excitement of discovery,’ says Berns. So, she created a comic, Atomic Size Matters.

When first considering the idea, she expected the comic to be ‘five pages and finished in a week [but it became] 55 pages long and [took] eight months to do’. It was worth all the effort. The reception and encouragement she received from her loved ones gave Berns the courage to self-publish and share Atomic Size Matters with the world.

And to the world it went. Former students used it to revisit the chemistry they’d learnt, parents used it to understand what their children were studying, teachers ordered sets for the classroom. Berns was continually overwhelmed to witness the extent of the impact her work achieved – it was ‘humbling to see and hear how my work helped people connect through science and silly drawings’. This feedback also reinforced an essential idea for Berns: ‘Starting meaningful conversations about science doesn’t require anything super expensive, just a lot of passion and patience to tell a story in an accessible way.’

Just as you don’t have to be the next Picasso to draw, you don’t need to be perfect to be a scientist

This idea is central to Bern’s teaching approach. She is now an associate professor in the chemistry department of Northwestern University in Illinois, US, where she uses comics to ‘bring levity and joy to a subject that can sometimes feel intimidating’. Many students who start her scientific communication class are generally unfamiliar with journal articles. To help introduce them, she breaks down a journal article into its constituent parts and allows students to reimagine the article in any format they like, from comic strips to podcasts.

Comics also have a presence in her regular chemistry class, where her love of illustration shines through in the diagrams and schematics she draws to complement her slides. She describes herself as not a skilled artist (though her comic suggests otherwise). However, she uses this as an analogy to encourage people into science: just as you don’t have to be the next Picasso to draw, you don’t need to be perfect to be a scientist.

Bridging worlds

Yann Brouillette, a chemistry professor at Dawson College, Montreal, Canada, has an alter ego: the Comic Book Chemist. He teaches a course that uses comic books to explain chemistry concepts to non-science students. By explaining the science behind comic book characters’ attributes like the blue skin of Nightcrawler and Mystique in X-Men, he bridges the gap between fiction and real-world science.

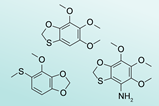

In reality, blue skin is a side effect of silver consumption also known as argyria (though this isn’t known to be the cause of the comic characters’ blue skin). Before the mass production of penicillin, silver – usually suspended in liquid – was prescribed by doctors as an antibiotic based on the element’s antimicrobial properties. Such treatments were eventually banned by regulatory agencies due to the adverse side effects.

Using examples like this to teach chemistry has been rewarding for both the students and Brouillette, who really values the moments when ‘the doubt in their eyes changes to understanding’. He realised just how much impact he was having on the students when two of his students from the comic book course switched into his chemistry class.

Bringing comics to life

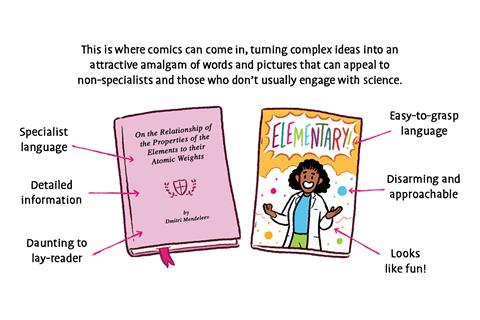

Often people are discouraged from creating comics because they think they can’t draw well enough. This is where illustrators like Edward Ross can be recruited to bring ideas to life.

A comic artist and writer in Edinburgh, UK, Ross ‘had great science teachers’ in secondary school who took huge, complicated concepts and condensed them down so they could be understood. This is something he now enjoys doing when making comics.

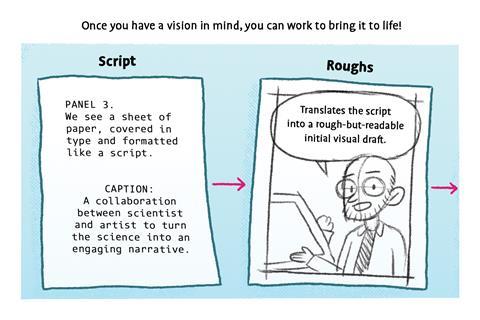

It’s now 270 years since the first comic book, Master Flashgold’s Splendiferous Dream (Kinkin sensei no eiga yume) by Koikawa Harumachi, was published and little has changed in how comics both look and are created. Script drafting, writing and editing must be combined with sketching, drawing and colouring. Science comics, however, require an additional step to ensure that the science is accurate and conveyed correctly.

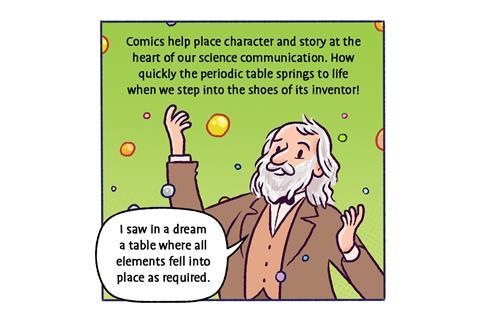

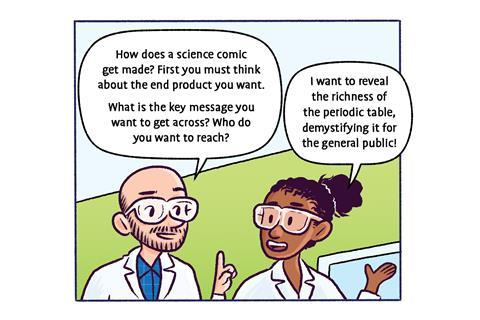

A fundamental principle is ‘having good discussions with the scientists’ about what the key takeaway is for the reader, says Ross. This sentiment is shared by scientist Saad Bhamla, an associate professor at Georgia Tech University in the US, who says that learning to ‘distil what the key essence of a paper is’ is a valuable step in making a science comic.

Relationships between scientists and illustrators can develop organically or be preexisting. The latter was the case for Ross and his collaborator, Jamie Hall, who he first met in secondary school and now researches microbiology and parasitology. Hall approached Ross with his university’s public engagement fund to collaborate on a comic book about the different parasites he was studying. Weeks later they’d created Parasites!

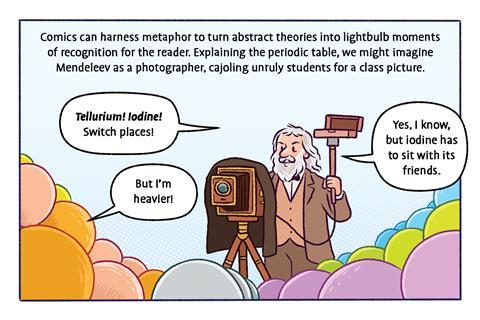

Ross recalls the difficulty of balancing accuracy and accessibility in this comic. It focused on parasites like trypanosomes that, on an evolutionary level, proliferate in the body and have an array of different coats; to evade the immune system, they change their coats and then proliferate again. This can be a difficult concept to explain accurately so to make it accessible, Ross used the metaphor of disguises. So, when the trypanosome was spotted by the immune system, they donned a different disguise to keep multiplying without being stopped.

Find inspiration from yourself – flaws, experiences, likeness

For Berns, making her comic accessible also improved the readability of her PhD thesis, which she was working on at the same time. She sometimes noticed that to understand a point in the comic a concept should have been introduced a few pages earlier. Continually going between the outlines for her comic and her thesis allowed her to recognise similarities between them – so much so that when she made changes to the order of her comic, she would then reorder the thesis. ‘Had I only focused on one or the other, I would have missed so many things, they fed off of each other,’ Berns says.

Berns also included other people in the development of her comic, brainstorming ideas with people in her research group to ensure that the comic ‘corresponds with the reality of the science [done],’ and asking others to read chapters to make sure they could be understood by someone outside of the research group. In her teaching now, she uses what she learnt from this process, actively differentiating between expert knowledge and lay knowledge instead of assuming that something is universally understood.

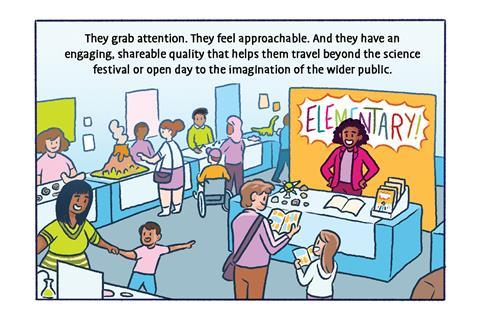

Widening access and breaking barriers

Bhamla’s science comic origin story begins with a grant application that included a question asking how would he use the grant to engage with the public. He thought to himself: ‘Who reads papers? 10,000 papers are published [but] no kids are going on to science.org and downloading a research paper’. Instead of creating ‘more barriers to cutting edge science than there already are with paywalls,’ he decided to apply for the grant, with a plan to create comics. And he got it. He and his fellow scientists partnered with a range of illustrators and created The Curious Zoo of Extraordinary Organisms. This has since become a series translated into Kannada, Telugu, Spanish, Chinese, Tamil and more, so that – like Berns – all who collaborated on the work can share it with their families and spread the wonder of science with more and more people.

Comics can do more than explain abstract concepts – they can also illustrate the value of academic research that doesn’t solely lie with external applications. Berns, who describes her PhD research as ‘fundamental and academic’, highlights that often science stories with direct applications are shared or heard about the most. While valuable, ‘there’s also room to talk about fundamental research, science that may not immediately lead to new products but still shapes our understanding of the world […] maybe one day the theories in my book will contribute to designing a new rocket ship or some other application, but without support for fundamental research, that future will never come.’

Like a meal, you need everything – a burger, fries, ketchup and a diet coke

Saad Bhamla

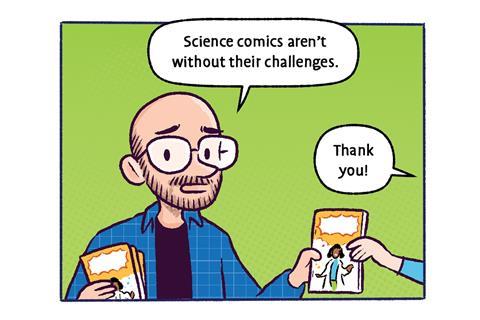

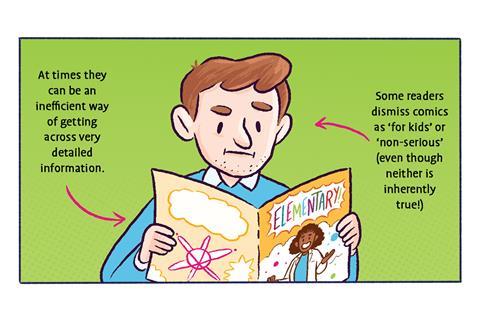

Comics are often mislabelled as for younger audiences. Ross recalls a science fair where he handed out science comics to adults who then passed it onto a child, thinking that was the intended audience. People then don’t give the use of comic books in science the credibility it deserves.

Brouillette experienced a similar situation when he tried to publish the first article that he and his colleagues wrote linking superheroes and science. It ‘had the chemistry of Captain America, Iron Man, Thor, Hulk, Ant Man, Ultron [and] was rejected everywhere,’ he says. Some peer reviewers claimed it was for children, and another said, ‘nobody knows who Iron Man is,’ despite him being one of the most well-known superheroes.

Using comic books to engage people with science and chemistry is complementary to other forms of science communication. Scientific articles, podcasts, videos, conferences and public talks all have their own associated positives and negatives and are suited for different contexts. Bhamla says that to reach as many people as possible, all methods should be considered: ‘Like a meal, you need everything – a burger, fries, ketchup and a diet coke.’

Top tips to make a science comic

Sitting down and making a comic can be a daunting challenge, but the consensus is to just do it. When starting, it helps to research what has been made in the target subject area to avoid repeating ideas. Brouillette also suggests when creating characters to find inspiration from yourself – flaws, experiences, likeness. ‘It’s OK to have perfect examples but we don’t need that many,’ he explains.

When judging the success of a comic, Bhamla emphasises avoiding focusing on quantitative results, such as how many comics were sold or how many people read it. Instead, look at qualitative measures, like the personal or emotional impact that the work has. ‘Sometimes just feeling that there is a scientist who cares so much about people, about science, about the joy of discovery and puts so much effort into [a comic] is enough to show that there are other human beings who care,’ he says.

No comments yet