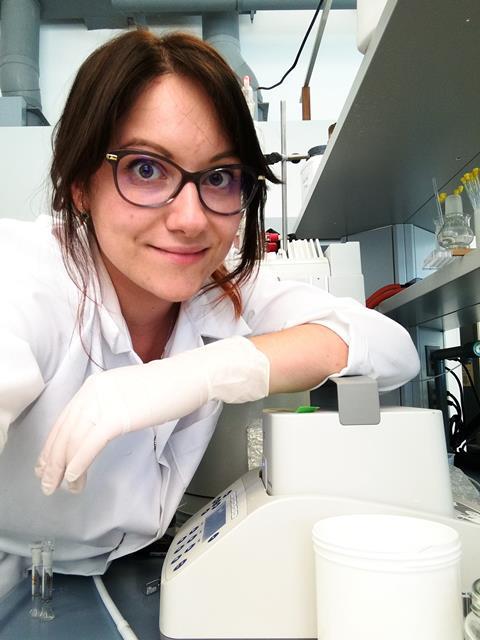

Biochemist Martina Hestericová on science communication and Instagram stardom

Martina Hestericová’s Instagram photos and videos have been viewed millions of times. Her posts are mostly from a lab at the University of Basel in Switzerland. They include her streaking petri dishes, freezing samples in liquid nitrogen, synthesising silica nanoparticles and playing with gooey polymers – all brief vignettes from her working life. ‘The most successful are the ones showing me while I work, which surprised me,’ says Hestericová. ‘Colours really work, such as chromatography on time lapse.’

Online success

Originally from Slovakia, Hestericová moved to Basel in 2013 to start a PhD on artificial metalloenzymes. By that time she was already heavily involved in science communication, administering a science problem-solving website, science-exercises.eu, for students. The site is a family affair, started in late 2008 when her grandfather retired after 40 years as a maths and physics teacher. ‘He got bored, and since my dad is a programmer, we decided to create a website for him so he could publish there. We didn’t know how successful it would become.’ Initially in Slovak, the website is now available in Czech and is being translated into English by Hestericová’s sister. It attracts more than two million visits a year.

‘The website was originally meant as a tool to help high-school students prepare for exams, but since I sometimes go deeper with the chemistry and biochemistry exercises it is suitable for first or second semester courses in college,’ she explains. After her grandfather died, she added chemistry and biochemistry sections, and has pledged to keep the website free to access in his memory. ‘I do science communication to make knowledge available to everyone.’

Hestericová’s Instagram posts began as a way of attracting attention to the website. However, the project has since blossomed to more than 20,000 followers, and she has roped in co-workers, her husband (an organic chemist), and her sister to add content. ‘We popped a bottle of champagne when I reached 1000 followers,’ she recalls. Around 80% of visitors are between the ages of 18 and 34, with more than half between 18 and 24. She often answers questions from students about her lab work, becoming a scientist or switching between course subjects. One video, a time-lapse of evaporation under reduced pressure, has garnered more than six million views to date. ‘It is not only about pictures,’ she muses. ‘It is always better when there is a story behind it.’

Three years ago, she began contributing to a start-up national newspaper in Slovakia, The Daily N. ‘My first try was terrible. I was writing about chlorophyll and even tried to write about how electron shifts could explain colour,’ she remembers. ‘I had to rewrite it, but the second try was better … writing for the Slovak newspaper is quite relaxing. I come home after a hard day in the lab, read a scientific article and write about it.’

Lab focus

Despite her success, she has continued her PhD research on combining proteins with metal catalysts to produce artificial metalloenzymes. These could catalyse reactions that would not ordinarily happen in nature, with optimisation aiming to boost their efficiency.

Hestericová studied biochemistry in university in Bratislava, before switching to organocatalysis for her masters. After she heard her future PhD supervisor speak at a conference in Slovakia in 2012, she asked him about becoming a PhD student. ‘I went from trying to avoid metals at all costs to protein engineering and working with artificial metalloenzymes containing transition metals.’ She is currently preparing to defend her thesis.

Factfile

Name: Martina Hestericová

Role: Forensic chemist, Lonza, Switzerland

CV: MSc in organocatalysis, Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovakia

* Note: Hestericová defended her PhD at the University of Basel, Switzerland in May 2018 after the interview was conducted.

Hestericová has decided to settle in Switzerland. In the future, she plans to translate her science website into German, then find someone to boost its physics and maths content. She is also keen to improve women’s participation in science in her adopted country, as it is not encouraged to the same degree as in Slovakia. ‘There is a need to show that women are good scientists and do as well as a man in communicating science,’ she says. ‘We have to start from the bottom and show young girls that anyone can become a good scientist. Social media platforms are ideal for this, as they directly target the young generation.’

No comments yet