DS Virgin Racing reveals the electrifying world of Formula E

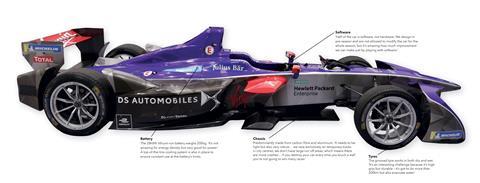

Sylvain Filippi is sat next to the sleek chassis of a Formula E car, its smooth lines and contours designed for aerodynamic poise, its silver and purple a sharp contrast to the sterile perfect white of the garage near Silverstone, UK. As chief technology officer for DS Virgin Racing, Filippi knows every part of this engineering marvel. A carbon fibre chassis; tyres designed to run on both slick and wet; a mix of aluminium and carbon in the rear-end and a battery that balances power, efficiency and weight. Every aspect of the car has been carefully considered, down to the last gram of weight. ‘In motorsport, if you can gain 0.5% efficiency somewhere, that’s huge and we’d throw everything at it. Translate it into lap time … that’s the difference between winning and being mid-field.’

DS Virgin Racing are mainstays in the sport, now in its fourth year: a 12-race championship spanning street races around the globe, with world-class drivers and engineers (many recruited from Formula 1) thrilling crowds with speeds of up to 140mph, accelerating from 0 to 60mph in a blistering three seconds. ’Road cars run at 300–400V,’ says Filippi. ’We run at 700V. It will go up again in the future, and when you increase the voltage you only get benefits – more power, more efficiency, less heat and so on. We are demonstrating here is we can increase voltage in a safe way … the next generation of road cars coming to market in two to three years will be at 700–800V. That validates the technology.’

We could make these cars the fastest ever designed, faster than Formula 1

The sport is surging forward, both in popularity and technology. Although the same batteries are used to power the cars as in the sport’s inaugural season, the competition between the teams is driving innovation into uncharted territory. ‘At that time,’ Filippi says, ‘[the battery] was designed to run a max power of 133kW throughout the race. Now, in season four, we’re running at 180kW with the same amount of energy.’ While progress is slowing, the team is chasing the fractions of a percentage in gains that make or break its chances in the sport.

‘We are allowed to use technologies that are borderline dangerous, cutting edge, not quite proven yet. You can easily see the potential. We could make these cars the fastest ever designed, faster than a Formula 1 car… it’s easy on a single lap basis because you get so much power and torque from electric motors. The only challenge is energy storage.’

Recruiting the best

It’s this hurdle that ties chemistry with the automotive industry. A confessed petrolhead, Filippi studied automotive engineering and management before moving to electric cars - which opened his eyes to the future of transport. ‘I realised how disruptive this technology would be,’ he says. ‘This technology was much more advanced than people realised and car manufacturers were advanced in their plans, even if they didn’t talk about it in public. I thought we needed a race series to promote it.’ This became the EV Cup; when the FIA, motorsport’s governing body, came up with the idea of Formula E, Filippi knew he had to be involved. ‘Virgin were keen to enter a team in Formula E but had very little expertise in electric cars, so that was a good match. So I co-started the team.’

The breakneck pace and unique nature of the sport means that there is no such thing as a typical day. ‘It varies from future car technology to what kind of software and tools we should be using, from long-term technology to short-term operational issues,’ Filippi says. While the team is based in London and Silverstone, in December the team celebrated driver Sam Bird’s win in Hong Kong, before finding themselves a month later in Marrakesh, Morocco; at the time of the interview, the team was moving on to Santiago, Chile.

As with all teams, Virgin is constantly looking for the best talent – particularly in engineering. The sport has strict regulations about only allowing 20 staff trackside, and no car changes allowed during the season itself (although software can be upgraded). However, there is a constant need for expertise. ‘Finding the right people is essential because we are limited by numbers: people have to be the best they can be. Formula E is going very quickly, and it’s of interest to many people. It’s for sure the future of the automotive industry, most likely the future of autosport… I need people who can understand electrical systems, and understand how we can design the most efficient power train. That requires deep, sophisticated knowledge of high voltage systems.’

Any of these technologies could literally change the world – and we’ll be the first to use them

The whole sport is also focused on lab innovations. While the technology is often the same across teams – the batteries were developed by Williams Advanced Engineering and the tyres by Michelin – attention is focused on chemical breakthroughs. ‘If we can find a way to store a lot more energy in a given volume and weight, that would revolutionise the entire industry,’ Filippi explains. ‘We follow that very closely, at the lab. In terms of chemistry, there are solid state batteries that are promising, and lithium–air. Any of these technologies could literally change the world – and we’ll be the first to use them.’

Real-world gains

As Filippi emphasises, the sport is really a proving ground for innovations in chemical engineering that will change the world. ‘If you look back in history, ABS and rear view mirrors were invented in motorsport and trickled down. But in the past 20 years the route to road has been quite long. For electric cars, it’s much simpler. There are fewer moving parts and so it’s much easier to translate them to the road. You could take the power train of this race car, and if you wanted you could build a road-legal sportscar and sit it on the M25. That’s not possible for other motorsports. Many manufacturers are coming into Formula E, and that’s the proof of the pudding… in the next two to three years you will see major announcements of new electric cars. They will be sports cars… and they will be directly derived from Formula E.’

But at the end of the day, it’s still a sport. Third in the championship, the DS Virgin Racing team have their eyes on success. ‘We’re all passionate about motorsport, we want to win races and championships,’ Filippi enthuses. ‘But we only do it because we have a purpose, we’re not going around in circles for the sake of it. It’s a great sport, it’s great entertainment, but it’s much better if you’re making a difference.’

Battery [Scott – this is located behind driver]

The 24 kWh lithium–ion battery weighs 300kg. ‘It’s not amazing for energy density but very good for power.’ A top-of-the-line cooling system is also in place to ensure constant use.

Chassis

Predominantly made from a single piece of carbon fibre as a safety shell. ‘It needs to be light but also very robust… we race exclusively on temporary tracks in city centres, we don’t have large-run off areas, which means there are more crashes… if you destroy your car every time you touch a wall you’re not going to win many races.’

Tyres

The grooved tyre works in both dry and wet. ‘It’s an interesting challenge because it’s high grip but durable – it’s got to do more than 200km but also evacuate water.’

Software [Scott - arrow to cockpit?]

‘Half of the care is software, not hardware. We design in pre-season and are not allowed to modify the car for the whole season, but it’s amazing how much improvement we can make just by playing with software.’

No comments yet