The materials expert on deciding to become a scientist, collaboration and fishing

Bin Liu is a distinguished professor at the National University of Singapore (NUS). She is known for her leading work with organic materials and polymers, and researches their application for biomedical, environmental and energy research. This year, she became the Deputy President (Research and Technology) at NUS.

My parents are the reason I am a scientist. My dad majored in French and as his career went on, he thought it was important that I studied for a major in a science subject. So, the main reason I studied chemistry originally wasn’t really driven by passion but by my parents.

I like solving problems and creating new knowledge. As a college student, I happened to do well with my grades. I began to think about a career in academia as not a bad idea. I didn’t feel like it was super challenging or difficult, I just enjoyed learning and discovering new things.

If I hadn’t become a scientist, I would have been a chef. When I was younger, I loved cooking and making food that was delicious. Now I’m getting a little older I look at it more nutritionally, paying more attention to what is healthy. Maybe after I retire, I will come back to cooking food more seriously.

The first year of my PhD was really difficult. I moved from China to Singapore and started studying polymer chemistry for the first time. I couldn’t get anything done, all my reactions were failing. I really thought about quitting my PhD for a few months, but then one day something clicked, and my reactions started to work. I don’t know what changed but I suddenly started to get positive results all the time.

I worked with around 50 other postdocs from around the world when I did my postdoc at UC Santa Barbara, US. It was competitive, we were all trying to produce the best results, but it was also very exciting. I was working with really smart people from around the world on one topic – it’s not an environment you find often.

There is more of a culture of collaboration in the US institutes than in most Asian universities. You can take small ideas and discuss them with people and suddenly they’re turning out to be something really big and exciting. I encourage my group to work with people in adjacent areas, because that can help us grow.

Life is more rewarding if we help elevate other people

If I had one piece of advice for younger researchers, it would be to be patient. I think it’s important that young scholars take a deep dive into whatever it is they’re doing and take time and patience with it. Breakthroughs always need patience.

The issues science needs to address are getting a lot more complex with time. When I was younger, we stayed focused on looking at smaller problems, but now the problems, whether it is climate change or a new virus, are much more complex. People need to work together across disciplines to solve a lot of these issues. None of these issues are single problems for single countries anymore, so we need more collaborations and good leadership.

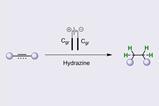

We shouldn’t underestimate the potential of machine learning and big data. I’ve done experiments with my colleagues using it to predict material properties and helping find molecules with desirable uses. It can help to imagine things pure chemists wouldn’t be able to do with just their brain. We still need people to be able to work on other things – we should look at science, engineering and chemistry as well. I tell young people to not just focus on AI, but to use it as a tool alongside other research.

Many top scientists aren’t interested in doing administration at all. I was inspired by my colleagues to serve the NUS [National University of Singapore] research community. Being a top scientist is great, but life is more rewarding if we can help elevate other people. I spend a decent amount of my time doing administration at NUS, with the motivation of trying to make a more conducive environment for my colleagues so they can progress faster.

I used to relax by going fishing. My dad always liked to fish, so when I was a little girl I would accompany him to fish every morning. When I was doing my postdoc, I used to go as well. You can be there for five hours and not get any fish, or you can be there for five minutes and catch one. It’s all about being patient.

I didn’t decide to become a scientist properly until I was doing my PhD. I wasn’t a passionate scientist from a young age or had dreams of becoming one. I moved to Singapore to do my PhD and I realised I could become a scientist. I am grateful to the generous support from Singapore and NUS to advance my career as a scientist.

No comments yet