The celebrated chemical biologist who dreamed of being a rock star before inventing the field of bioorthogonal chemistry

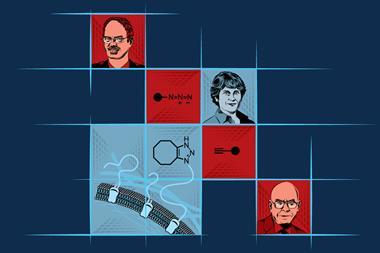

Carolyn Bertozzi is a chemistry professor at Stanford University whose group develops chemical tools to study the glycobiology behind diseases like cancer, tuberculosis and Covid-19. She won the MacArthur ‘genius’ award in 1999, and shared the Wolf Prize in Chemistry earlier this year for, among other things, founding biorthogonal chemistry. She also became the first woman to receive the Lemelson-MIT Prize faculty award in 2010, and was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2017. She was speaking to Rebecca Trager

I was born in Boston, Massachusetts, and grew up in a suburb with two sisters. My father was a physics professor at MIT, and my mom, as women of her era often were, was a full-time mom. She didn’t have the opportunity to go to college when she was younger, but later in her 60s – after we were all out of the house – she actually did go and get a college degree.

I wanted to be a professional soccer player as a kid growing up. Back then, there was no such career as that for women, so it wasn’t a very informed idea. I would have also loved to have been a rock star. When I was in high school, and then even in college, I fantasised about being a musician.

I didn’t prioritise science over anything else until I was taking biology, chemistry, maths and physics in university because I thought maybe I might want to go to medical school someday. And then chemistry really caught me, especially organic chemistry. I just thought it was so inherently logical and beautiful and visual, and it really came to life for me in a way that other classes had not.

In college, I played in a band named Bored of Education. We played at parties at college and at frat parties at other universities around the Boston area. We were mostly a cover band with a few originals, and we played 80s music. The leader of the band was the legendary rock guitarist Tom Morello. At the time he was just a 20-year-old college student, but he went on to found Rage Against the Machine and Audioslave. It was his band, and he recruited me to play keyboards for a year or two. That was my brush with fame.

As an undergrad doing physical chemistry research I really enjoyed the lifestyle of working in the lab. I had an affinity for that, so then I decided to go to graduate school at the University of California, Berkeley, and ended up working in the lab of a young brand-new assistant professor whose name was Mark Bednarski. He introduced me to carbohydrate chemistry, but became ill with colon cancer about three years into my PhD and basically took a leave of absence before leaving his job. So, for the last two years of my PhD, I and a few other labmates who were far enough along just kind of finished our research on our own.

I had to learn to be very independent, and to run my own research programme. As the senior student in the lab, I was in a kind of mentorship role. And indirectly through my interactions with Mark, I got a much closer look at cancer diagnosis, treatment, and what it’s like to be a patient.

Even in college, I fantasised about being a musician

I walked away from chemistry for a couple of years and went full on biology, after deciding to work in an immunology lab at the University of California San Francisco medical school. This was in the early 1990s, and at that time it was not yet common for PhD students from one discipline to do postdoctoral work in a completely different discipline. It was considered a strange thing to do.

Music is very much a solo endeavour for me – I just play piano by myself late at night with a headset on. It’s good stress relief, it’s a good way to try to open up the creative doors and get out of my head, and get my brain to exercise other parts. I play everything from pop music to rock and roll, to jazz, showtunes and Christmas carols.

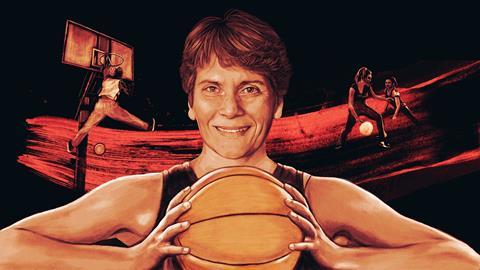

Playing street basketball is another thing I like to do when I need to be able to just think. There is a basketball hoop in front of my house, and if I’m by myself just shooting hoops I find that very meditative.

My first car of was a piece of junk. I bought it the summer after college and used it to drive all the way from Massachusetts to California to set up shop in graduate school. It was a four-year-old 1984 Toyota Tercel, totally stripped down with no power windows. It was a mustard yellow, hideous, and patched together with duct tape. I drove that car pretty much until I got tenure at UC Berkeley as a professor, and by that time it was dead.

Geopolitical forces are a threat to science. They have undermined our ability to benefit from the global talent pool. For example, when there were US government forces that went after Chinese scientists at MIT and elsewhere, that made it harder for us to have scientists from overseas come and work in our laboratories here in the US. It has become harder for international trainees to get visas, especially if they’re from China. That interfered with our ability to collaborate on the global scale.

I’m a very passionate advocate for diversity, equity and inclusion. The diversity of my lab members over 25 years has probably been better than the average chemistry lab, and I think that that has been really important for my success as a scientist. To have people with different backgrounds, different mindsets, different priorities, has helped me to become a better and more impactful scientist.

No comments yet