Alchemists are being reappraised after being dismissed for centuries. Lawrence Principe deciphers their writings and discovers some sophisticated chemistry

Alchemy and its practitioners have often gotten a bad reputation. Since the eighteenth century, alchemy has generally been associated with fraudulent practices, occult hocus-pocus, or simply a deluded and greedy quest for making gold. Many historical accounts dismissed it as an obstacle to the emergence of ‘real’ chemistry, which is the way that some eighteenth-century writers chose to portray it.

Nevertheless, during the past thirty years or so, historians of science have been paying fresh attention to the ‘noble art’ of alchemy, asking who the alchemists were, what they really did and thought, and how their work figured in the broader intellectual and cultural context of early modern Europe. As a result, alchemy is now enjoying an unprecedented scholarly revival, and many old assumptions about it are being replaced with better, more contextualized understandings.

It is true that one major goal of alchemy was the transmutation of base metals like lead into gold. This quest endured from alchemy’s origins in Greco-Roman Egypt in the first centuries AD, through the Islamic and Christian middle ages, to its great heyday during the scientific revolution of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. But far from being a groundless or purely fanciful endeavour, alchemy was actually grounded in increasingly sophisticated theories of matter that, although finally proven incorrect, were nonetheless based to a large extent upon observations of natural and experimental phenomena.

The alchemists thought of metals not as elements as we do, but as compounds: composed of two or three more fundamental substances combined in differing proportions, degrees of purity or even particle size. As a consequence, a skillful operator should be able to adjust these variables artificially, thereby turning one metal into another. In this way, the alchemists sought to improve upon nature, creating better, more valuable materials in the laboratory from the raw substances afforded by the natural world; chemists today should find this goal very familiar.

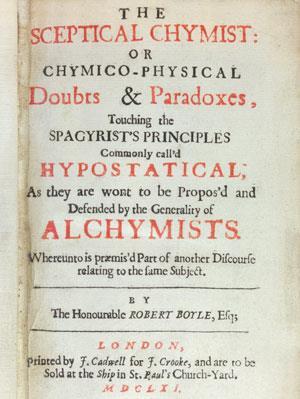

Robert Boyle and the philosophers’ stone

While some alchemists tried laborious methods to analyze and purify the metals, many sought instead to prepare a hypothetical reagent that when added to a molten base metal would cause the transformation in a single step. They called this sought-after substance the elixir or the philosophers’ stone. Many alchemists claimed that they were close to a breakthrough in preparing it, and many others asserted that they had actually witnessed a transmutation of lead into gold using the stone. Among the latter is the famous Robert Boyle (1627–1691) who claimed to have seen transmutation three times, and to have satisfied himself of its authenticity in one case by analyzing the gold that was produced. He himself sought to discover the means of preparing the stone for forty years, and when he thought he was close, petitioned Parliament (successfully) in 1689 to repeal a long-standing English law that forbade transmutation.1 What he and other witnesses actually saw remains one of the intriguing questions for historians of chemistry to ponder.

In their search for the stone, alchemists developed many of the instruments and techniques that are still in use by chemists today. Their practical experimentation led them to realise, for example, that weight is always conserved – a finding contrary to the teachings of Aristotle that then formed the basis of scientific knowledge. In the middle ages, some alchemists already used this principle to monitor the course of their processes in ways that the unaided senses could not do.

Around 1350, the Franciscan friar John of Rupescissa argued that when mercury is sublimed from a mixture of salts, it must incorporate some new ‘invisible’ substance from the salts because the sublimed mercury ‘whiter than snow’ weighs more than the initial liquid mercury.2 Reading Rupescissa’s description of the process, it is fairly easy for a modern chemist to conclude that the Franciscan friar had produced mercuric chloride. The only problem is that Rupescissa mentions using vitriol (copper sulfate) and nitre (potassium nitrate), but no chlorides.

How then did he make what is obviously mercuric chloride? It is possible that his nitre was so impure that it contained sufficient chloride, but it is more likely that he intentionally ‘omitted’ the crucial ingredient from his account. After all, the friar thought this sublimation of mercury was the first step in making the philosophers’ stone, and he was seeking the stone because he believed that the antichrist was about to appear and the Christian world would need a means to support itself while fighting against him. Why then publish an account so clear that the antichrist’s minions might also learn how to make the stone? No further explanation of John’s motives should be needed for those of us today who are accustomed to the analogous threats of political and corporate espionage. But alchemy’s culture of secrecy, of which John of Rupescissa provides just one simple example, has been the biggest obstacle to gaining a more accurate understanding of what alchemists were really doing.

Fiery dragons and magical steel

Alchemical writers routinely used codes, cover names, riddles, false leads and allegorical language to hide the details of their activities from most readers. But their language was also carefully crafted to reveal these details in a measured way to those who could understand their methods. They rarely called the substances they used by their common names, but instead invented imaginative code names for them that usually drew metaphorically upon one of the material’s physical or chemical properties: the ravenous wolf (a corrosive), the eagle (a volatile substance), the king (a precious substance), the sordid whore (a substance that combines easily with many other materials) and so on. Many took the next step of casting these personified reagents into extended allegorical narratives that concealed laboratory operations. Take for example Eirenaeus Philalethes (the pseudonym means ‘peaceful lover of truth’) who wrote some of the most popular alchemical texts of the seventeenth century; Isaac Newton valued him very highly as a guide for his own alchemical researches, and probably developed his own matter theories from Philalethes’ ideas.3 Philalethes tells the reader to begin in the following way

Take our Fiery Dragon that hides the Magical Steel in its belly, four parts, of our Magnet, nine parts, mix them together with torrid Vulcan…throw away the husk and take the kernel, purge thrice with fire and Sun, which will be easily done if Saturn sees his form in the mirror of Mars. Thence is made the Chameleon or our Chaos…the Hermaphroditical Infant infected with the biting of the Corascene mad dog…4

Beneath this colorful language, what he is really describing is a replicable process for isolating antimony (the hermaphroditical infant) from its native sulfide ore (our magnet or Saturn) using iron (our fiery dragon or Mars) as the reducing agent. Even Philalethes’ allusion to rabies reveals his chemical knowledge. This rabies, or hydrophobia, refers to antimony’s ‘fear’ of metallic water – that is, mercury; in plain English, antimony will not form a stable amalgam.

The allegory can be confidently deciphered because the man behind the mask of Philalethes, the Bermuda-born and Harvard-educated (class of 1646) George Starkey, gave the same process in perfectly clear language in a private letter to his sometime tutee and trusted friend Robert Boyle, and recorded it in beautifully detailed laboratory notebooks, some of which survive to this day. Thus, alchemists were accustomed to write in two very different styles, a bizarre metaphorical language for more public consumption and a clear and straightforward descriptive style for guarded private use. The historical result is that the published works survived while most of the private materials perished, and so most later readers saw only the extravagant imagery without having a key to decode it, and easily concluded that such writings were no more than imaginative ravings or the markers of mental instability.

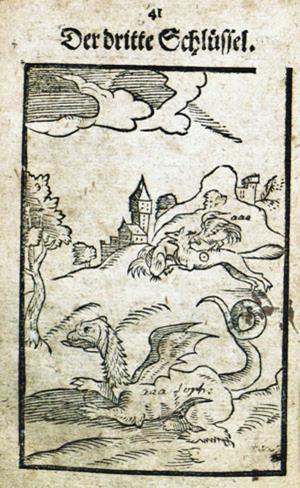

A further development in alchemical metaphorical language was the creation of allegorical images – a variety of woodcuts and engravings that depict bizarre events that are supposed to contain a hidden message related to practical operations. If anything, these alluring images have often made alchemy seem even more distant from chemistry, and the alchemists more strange. But they do fit into the wider context of early modern imagery that was intended to convey hidden meanings. Think of Renaissance and Baroque painting, theatre or poetry, full of images, allusions, symbols and double meanings that most of us today in our narrow, literal-minded modern world now need an expert to decipher for us. One key for unlocking hidden alchemical messages lies in trying to reproduce the chemical processes they seem to encode. Some patient laboratory work reveals that many of these images actually bear witness to painstaking experimentation.

The golden key

One of the most famous sets of alchemical images are the Twelve Keys – twelve allegorical emblems attached to the name of Basilius Valentinus, a supposed German Benedictine monk of the fifteenth century, but actually the composition of an anonymous author around 1600. The idea behind them is that if the reader can decipher these images and the short narratives that accompany each of them, he should then be well on the way to preparing the philosophers’ stone. The third key is presented as a crucial step in the process. The two preceding keys can be interpreted to describe the purification of gold and the preparation of a highly corrosive acid similar in composition to aqua regia; these are the two reagents to be used in the third key.5

The text of the third key states that ‘the king’ must be ‘conquered with water…utterly shattered and made invisible’. This seems a fairly straightforward direction to dissolve the gold (king) in the acid (water) to produce a transparent solution in which the gold is now ‘invisible’ in the form of dissolved gold chloride. ‘But his visible form must this time appear again,’ for the hopeful alchemist cannot go forward ‘unless the salty sea has swallowed the corpse, and then entirely spit it out once again’. Thus the invisible gold must be recovered in its original visible form; the easiest way to do this is simply to evaporate the solution – the thermally unstable gold chloride would quickly decompose back into gold. However, these directions seem circular; they lead nowhere. Valentinus’s instructions then become more bizarre:

…then raise up [the king] in degree so that he far surpasses all the other stars of heaven in brightness…this is the rose of our masters, scarlet in color, and the red dragon’s blood…Endow him with the flying power of a bird as much as he needs, thus the rooster will eat the fox, be drowned in water, be made living by fire, and be eaten in return by the fox, so that like and unlike are made alike.6

In the woodcut, the reader can see the red dragon in the foreground and the strange pair of a fox and a rooster mutually consuming one another in the background. Can there be any chemical meaning here? The ‘raising up’ and ‘flying power’ seems to imply that the gold is somehow to be volatilized, but such a process scarcely seems reasonable – and indeed claims by alchemical authors to volatilize gold were met with ridicule in their own day. Nevertheless, attempts to replicate the process verified its reality. If the acidic solution of gold chloride is distilled in a retort, gold – the king’s ‘spit out corpse’ – is initially left as a residue. But if fresh acid is immediately poured over the residue, distilled off to dryness, and the process repeated several times, after a few repetitions, beautiful, gleaming ruby-red crystals of gold chloride can be sublimed into the neck of the retort.

This alchemist was a highly competent experimentalist

The ‘secret’ here is that the original experimenter must have repeated the dissolution and distillation several times in quick succession, thereby filling his apparatus with chlorine from the decomposed salt. Under these conditions, he unknowingly took advantage of an equilibrium between gold chloride and its components – the atmosphere of chlorine allowed the gold salt to sublime at a moderate temperature. Thus the very ‘unlike’ volatile acid and completely non-volatile gold are made ‘alike’; that is, joined together in red crystals that sublime unchanged. A similar process was independently rediscovered and chemically explained in 1895, three hundred years after Valentinus first carried it out.7

This sublimation of a thermally unstable gold salt is a tricky operation in a modern laboratory, even with the assistance of modern technology and chemical knowledge. Imagine then, how truly remarkable it is that an alchemist carried it out successfully four hundred years ago using unannealed soft-glass vessels and a charcoal fire where temperature could be gauged only by touch and experience and controlled only by opening and closing furnace vents. Clearly, this alchemist was a highly competent, patient, and experienced experimentalist; the kind of a person one would gladly hire in a lab today – provided that they agreed to write research reports in a straightforward manner.

Alchemy was a wide-ranging and diverse practice in early modern Europe. Its practitioners sought not only the philosophers’ stone, but also made and sold a wide range of other more attainable chemical products: improved medicines, pigments, dyes, alloys, cosmetics, and so on. Alchemy’s adherents ranged from university professors, physicians and noblemen, to silversmiths, clerics, brewers, and drapers – not to mention quite a few hucksters. Its concepts and promises influenced fine art, literature, and poetry.

Despite its culture of secrecy (or perhaps because of it), alchemy fired imaginations and tinctured thought in multiple areas to an extent we are only now coming to realize. But beneath it all, in the smoky laboratories of its practitioners, lay what we would quickly recognize as chemical operations, powered by the dream of understanding matter and controlling its transformations in order to generate new, more perfect, more valuable products. In this way, alchemists were very much the crafters of the traditions and goals of chemistry as it continues today.

Lawrence Principe is the Drew Professor of the Humanities in the Department of the History of Science and Technology and the Department of Chemistry, and director of the Charles Singleton Center for the Study of Premodern Europe at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, US, and the author of The Secrets of Alchemy

References

1 L M Principe, The aspiring adept: Robert Boyle and his alchemical quest, Princeton University Press, 1998

2 John of Rupescissa, De confectione veri lapidis philosophorum, ca. 1350; in J J Manget, Bibliotheca chemica curiosa, 1702

3 W R Newman, Gehennical fire, Harvard University Press, 1994

4 E Philalethes, Introitus apertus ad occlusum regis palatium, 1667

5 L M Principe, The Secrets of Alchemy, University of Chicago Press, 2013

6 B Valentine, Von dem grossen Stein der uhralten Weisen, 1599

7 T K Rose, J. Chem. Soc., Trans., 1895, 67, 881 (DOI: 10.1039/CT8956700881)

No comments yet