Most of the famous Benin bronzes – artworks in the forms of heads, plaques and figurines made by the Edo people of west Africa between the 16th and 19th centuries – are made from brass that originated in the German Rhineland, a new study has found.

The discovery casts new light on the artworks, many of which were looted during a British military expedition in 1897 that brought the Edo Kingdom of Benin to an end. The Kingdom of Benin is separate from the modern republic of Benin, and its territories were eventually absorbed into Nigeria, a British colony at that time.

An estimated 5000 Benin bronzes are now found in collections around the world, including at the British Museum in London and The Met in New York. Nigeria has asked for their repatriation, but fewer than 100 have been returned.

Tobias Skowronek, a geochemist at the Technische Hochschule Georg Agricola in Bochum, Germany, who led the new study says it was suspected the source of the metal were melted-down ‘manillas’ traded by the Portuguese into West Africa.

But where those manillas were purchased – in Antwerp, or in Amsterdam, or in London – and where they were mined wasn’t known, he says.

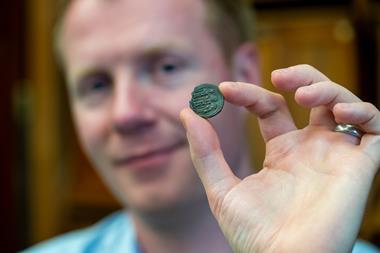

Manillas were horseshoe-shaped copper-alloy rings that were used as a type of money in west Africa by European slavers and traders from the 16th century. They were an important source of copper and usually alloyed with zinc to make brass. But the metal was often called ‘bronze’, which implies the presence of tin.

Skowronek says that this is the case for the Benin bronzes: ‘The Benin metal is mostly brass or leaded brass, sometimes with [small] amounts of tin,’ he says.

To determine the source of the metal in the Benin bronzes, Skowronek and his colleagues analysed 67 manillas recovered from five shipwrecks in the Atlantic and three land sites in Europe and Africa, to determine their lead isotope signatures and trace levels of antimony, arsenic, nickel, and bismuth.

The researchers found strong similarities between the manillas used in early Portuguese trade and the metal used in more than 700 of the Benin bronzes, according to earlier studies of their chemical compositions.

In addition, they found the composition of the copper in the Portuguese manillas matched copper ores mined in the German Rhineland, which suggests that Germany was the main source of the metal – a discovery that is likely to apply to most of the Benin bronzes, Skowronek says.

Maritime archaeologist Sean Kingsley, the editor-in-chief of Wreckwatch magazine, says the discovery is a testament to the scientific value of shipwrecks.

He highlights the irony in Europe’s cheapest metal ending up in the finest art in West Africa, noting that manillas were ‘a sinister cog in a machine designed to get West Africa hooked on Western goods’.

But Benin’s craftspeople were equal to the challenge, adds Kingsley. ‘The Victorian world was shocked how accomplished [Benin’s] artists were and started re-thinking how these “heathen savages” thought and lived,’ he says.

References

T B Skowronek et al, PLoS One, 2023, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0283415

No comments yet