Next week, negotiators from almost every UN member state will meet in Switzerland to thrash out the final details of a global treaty to end plastic pollution. The discussions have dragged on for over three years and were supposed to conclude at a fifth round of talks held last December in South Korea. However, negotiators adjourned that session without reaching an agreement on the treaty’s text, and will now reconvene in Geneva in an attempt to resolve the most contentious issues.

Since the beginning of the negotiations, dividing lines have been drawn up between a so-called ‘high-ambition coalition’ of countries favouring a stronger treaty, and a smaller number of petrostates that have sought to delay and weaken it.

Two key topics have been at the centre of the debate: commitments to reduce production of virgin plastic, and potential restrictions on using particularly harmful chemicals in the manufacturing process.

Curbs on production

The UN resolution that initiated the negotiations calls for a treaty that addresses the ‘full lifecycle’ of plastics. Many observers note that this implies that the treaty should include measures to reduce the unsustainable quantities of plastic that are currently produced globally – around 500 million tonnes each year.

‘All of the modelling and studies’ show that capping production is essential if the treaty is to achieve its aims

Bethanie Carney Almroth, University of Gothenburg

At the previous meeting in South Korea, over 100 countries endorsed Panama’s proposal that the treaty should oblige every country to report how much plastic it produces and what measures it is taking to reduce this to an agreed level.

However, the ‘like-minded group’ of countries with large petrochemical industries – which includes China, Iran, Russia and Saudi Arabia – has consistently attempted to steer the treaty’s focus away from production, and instead towards the end of the plastic lifecycle. They argue that the solution to the plastic problem is in waste management, recycling and moves towards a ‘circular economy’.

‘According to science and according to the more ambitious countries, [the plastic lifecycle] starts with the extraction and production of the raw materials and the raw plastics, all the way through to products, waste management – or mismanagement – and then environmental contamination,’ notes Bethanie Carney Almroth, an expert on the environmental effects of plastic based at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. ‘But there are countries that are trying to shorten that to [just] products to waste … which is problematic.’

Carney Almroth is one of the co-coordinators of a group called the Scientists’ Coalition for an Effective Plastics Treaty, which aims to provide policymakers with independent scientific advice on topics related to plastic pollution. She notes that ‘all of the modelling and studies’ show that capping production is essential if the treaty is to achieve its aims. For example, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s analysis of possible policy scenarios concludes that strategies that focus on waste management alone ‘will likely fail’ to eliminate plastic leakage into the environment.

Plastic pollution facts

- Plastic production doubled between 2000 and 2019, to 460 million tonnes a year

- More than 10 billion tonnes have been produced over the last 70 years

- Around 736 million tonnes of plastic will be produced in 2040

- Only 9% of plastic waste is recycled globally

- Microplastic particles have been detected in human organs, including the brain, kidney and liver, as well as the cardiovascular, respiratory and reproductive systems; they have also been detected in the placenta, breastmilk and semen

- Plastic pollution has been discovered in the world’s most remote places, including in the deepest ocean trenches, Mount Everest, the upper atmosphere and the planet’s polar regions

Chemicals of concern

Another important issue for negotiators to grapple with is how the treaty will regulate harmful chemicals associated with plastics.

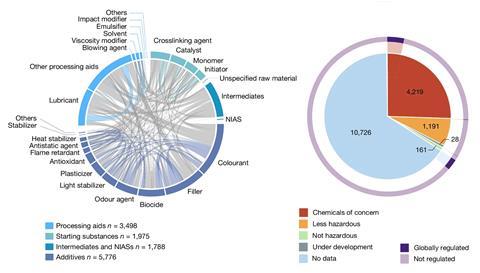

Thousands of chemicals are used in the manufacture of plastics, from catalysts, crosslinking agents and monomers used to make the raw polymers, to property-enhancing additives like colourants, flame retardants and heat stabilisers. Other chemicals involved at various stages of the process can find their way into the final products, including solvents, emulsifiers and lubricants. And after a plastic product has been made, the chemicals within it can then begin to break down, producing yet more impurities and degradation products.

Sometimes there is a lot of information on one chemical and no information on another that is very similar

Laura Monclús, Norwegian University of Science and Technology

In July, a report in Nature presented an inventory of more than 16,000 known plastic chemicals. The researchers behind this PlastChem database, identified more than 4200 ‘chemicals of concern’ – substances that pose a threat to the environment or human health due to their persistence, ability to bioaccumulate, mobility or toxicity.

For over 10,000 of the other chemicals, no publicly available safety data exists, while only 161 have evidence to suggest that they are not hazardous.

‘Sometimes there is a lot of information on one chemical and no information on another that is very similar, chemically speaking,’ explains Laura Monclús from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim, who led the project. ‘And that has happened in the past, for instance in the bisphenols case: there was regulation on bisphenol A, and then, of course, industry had to replace it with something else, so they replaced it with bisphenols S, B, M, AF – so there are many more, and what we realise now is that they also are harmful.’

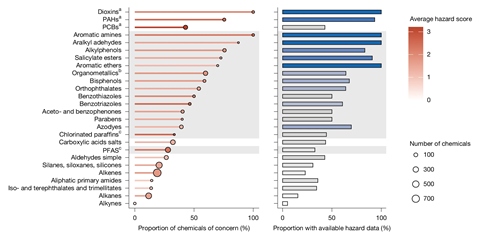

With this in mind, Monclús and her team identified 15 ‘priority groups’ of chemicals associated with plastics. These are classes of compounds that are not currently regulated globally, even though more than 40% of the substances within each group are known to pose environmental or health hazards.

Many observers hope that the plastic treaty will provide a means to ban or regulate such classes of harmful chemicals in the manufacture of plastics. However, Carney Almroth notes that the section of the treaty addressing chemicals of concern has already been negotiated down.

‘There are some proposals put forth with initial listings of what those chemicals might be, what the criteria to address them might be and which products could be addressed. It’s a very short list at this point: there’s a few phthalates, bisphenol A, two metals – lead and chromium,’ she says. ‘That would potentially be okay if the treaty includes a mandate for some sort of expert subsidiary body … to strengthen and develop that and to add to that list in the future – that’s also a point yet to be negotiated. But as it stands right now, it’s obviously not sufficient.’

In addition to banning or regulating the use of chemicals of concern, Monclús’s team recommends measures that would force industry to be more transparent about the materials used during plastic manufacture.

At the previous session in South Korea, industry representation dwarfed that of any country or civil society organisation

‘We compiled information that we could from different sources – peer review and also from government. But of course, we also notice that there is an important gap of information from industry, because it’s not clear enough which chemicals are used in which types of plastics,’ she explains. ‘So, our … recommendation is that it is important that there is public disclosure of these chemicals that are used in plastics.’

A matter of urgency

Throughout the negotiations, concerns have been raised about the sidelining of independent experts from the talks and the huge presence of industry lobbyists – at the previous session in South Korea, industry representation dwarfed that of any country or civil society organisation. In fact, industry’s 220 attendees outnumbered the delegations from all EU countries combined.

Despite this, a majority of UN member states are still pushing for a strong treaty. In June, representatives from 95 countries reaffirmed their commitment to tackling the full lifecycle of plastics and called for ‘a global target to reduce production’ of primary plastic polymers and an obligation to phase out chemicals of concern. What remains to be seen is whether they can push through these demands, or whether the negotiations’ rules that require a consensus among participating countries will enable a minority of states to strip out the treaty’s most effective measures.

‘There’s a lot of really pressing issues around plastics pollution, around health impacts, around the costs that are quite acute and, in reality, existential for some people on this planet already today – so there’s an urgency to complete this treaty,’ says Carney Almroth. ‘It will be, obviously, years before it’s active and fully effective, even if it were decided now in Geneva. There are countries that really do want to finish this, the question is whether or not it’s possible under consensus, without going down to the lowest possible denominator.’

No comments yet