Online auditing platforms may spell the end for log books and shelves of forgotten chemicals

University researchers have no doubt ordered a solvent from their chemical stores only to find an unused bottle lying in a cupboard. Now, groups of chemists around the UK are introducing computerised management platforms to tap into these wasted chemical resources and monitor the journey reagents take from procurement to disposal. And their efforts are already saving cash-strapped departments thousands of pounds a year.

‘Resource management is absolutely key at the moment,’ says Charlie Dunnill from Swansea University, UK. ‘It is a fundamental problem – it really is very, very serious.’ In his previous position as a Ramsay fellow at University College London (UCL), Dunnill decided to try to tackle this problem.

He quickly noted there was no way of knowing where certain chemicals were within a department and the quantities each group had. This lack of communication leads to researchers ordering in excess and struggling to keep costs down.

‘Very often, especially in organic chemistry, you will buy 10g of something, but you only need 2g of it,’ explains Dunnill. ‘You end up with 8g on the shelf, which doesn’t sound like much, but some of these materials cost £1000 a gram. So if three people in the same department each need 2g of it and they each have to buy 10g, you’ve wasted a significant amount.’

Jennifer Harman, a technical manager in life sciences at the University of Hertfordshire, and her colleagues are also trying to tackle this wasteful culture. ‘We’ve just done a stock take of one of the solvent stores and we do have situations where we have ridiculous amounts of certain solvents,’ she says. ‘I found out we have got 131 litres of one specific grade of one specific solvent.’

Crystal clear

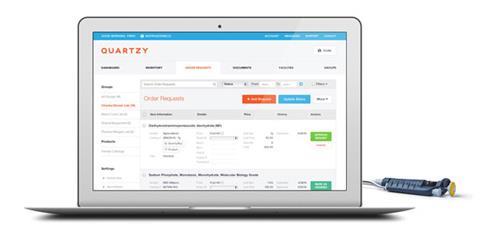

To account for such vast resources, Dunnill has adapted Quartzy, a free online management platform that keeps track of chemical stocks and safety data, for lab operations at UCL and now Swansea. Founded by Adam Regelmann and Meena George at Columbia University in 2009, the platform was born out of the same frustrations experienced by Dunnill and Harman.

Using Quartzy, a lab is able to track a chemical from cradle to grave. ‘I have adapted Quartzy and I have a one bottle, one line policy,’ explains Dunnill. As each bottle arrives in the department it is given a reference number sticker, which is logged in the database so users can locate and track it no matter where it is. Researchers are able to spot a reagent they require and request it from the lab in question, thereby avoiding unnecessary purchase orders through central stores.

It is a rather simple way of tracking stock, but the benefits have been immediate for UCL’s chemistry department, with savings estimated to be up to £90,000 a year.

As the platform is updated online, it also offers an advantage that an excel spreadsheet or log book couldn’t provide. ‘I could actually stand outside the labs here at Swansea … with the fire brigade and say “in this lab you have got x, y and z”, which is really useful and you can do that off a tablet outside the building,’ says Dunnill.

Supermarket sweep

For Harman, such systems must also have built-in safety measures to ensure chemicals only go to those trained in their proper handling, while also allowing for quick and easy access.

Adopting a different strategy to Dunnill, Harman has found inspiration for an auditing platform from an unlikely source. Along with her husband Andrew, a former technical officer in the pharmacy labs at the University of Hertfordshire, Harman started a board game production company in 2015.

‘We were bringing out our first game, and having to come to terms with this horrible thing called barcodes and how do you buy a barcode,’ Harman says. Dealing with this electronic point of sale (EPOS) system triggered an idea about how such retail processes relate to departmental chemical stores.

‘I guess it was one of those classic light bulb moments that [Andrew] had, which basically said: “Hang on, we’re dealing with a shop here”,’ she says. ‘We are trying to restrict access to goods to people who shouldn’t have them – we are just like an off-licence.’

There will have to be some behavioural change with the people using chemicals management systems

Using this philosophy, Harman has carried out an EPOS trial in a central store at the university’s biochemistry labs. Each chemical is assigned a barcode to identify it and a non-hierarchal hazard level from zero to nine – zero being ‘no known hazard’, for instance, or nine equating to controlled drugs. One chemical can have a combination of these hazard levels.

The product is scanned upon leaving the stores, but not before the user’s competence to handle it is checked. Harman has again looked to the retail industry for an easy method of checking through scanning – the loyalty card. Each user’s card will have all the information needed to confirm their credentials (budget code, department and which chemicals they are capable of handling).

‘We’re going to the research supervisor or line manager and saying these are the categories, you tell us what your people are trained and competent to use,’ explains Harman. ‘It’s putting the responsibility back on the research supervisor to assess the research competence of their students or members of staff.’

The company you keep

Even though such platforms appear more fool-proof than pen and paper, they still share the same mode of input – people. ‘My worry is we’ve been working with a small group of people who are committed and understand the system and we’ve taken a lot of time to explain it,’ comments Harman. ‘The difficulties are actually going to come when we broaden it out to people who don’t know, don’t want to know and actually don’t want to change anything.’

But by making the systems simple to use, such auditing advocates believe the culture of excess will begin to shift. ‘Whilst there will have to be some behavioural change with the people using it, we’re trying to make that as small and painless as possible,’ argues Harman.

It’s a sentiment that Dunnill shares and one that he believes researchers will invest in and respect: ‘You need to keep it really simple and really user-friendly – the only way I can see to do that is by trusting your staff and by keeping it open.’

No comments yet