More than 200 top chemists have signed two letters complaining of their frustration at how the EPSRC makes funding decisions

UK chemists are in open revolt over administrative interference in their field by the main grant funder. Two separate letters have each gathered the signatures of more than 100 top chemists and express outrage over the manner in which the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) is deciding the future of chemistry. The chemists say that the EPSRC has overstepped its bounds as a funder and is trying to tell the scientific community which areas of research to prioritise without the scientific knowhow to do so.

The letters are a response to the EPSRC’s recent announcement of how it would focus cash in areas of ’national importance’. Some sub-disciplines will be squeezed with synthetic organic chemistry among the first - along with cold atoms and molecules - to feel the pinch.

In one letter sent to the Prime Minister, Tony Barrett, Glaxo and Sir Derek Barton professor at Imperial College London, made the case that unfounded cuts to synthetic organic chemistry would ’injure’ the UK economy. The letter was signed by chemists and captains of industry from around the world in the pharmaceuticals and chemicals sector, including seven Nobel laureates.

At the same time, Paul Clarke, a synthetic chemist at the University of York, UK, sent another letter to the science minister, David Willetts, requesting an inquiry into how the EPSRC operates. Clarke says that the final straw was the council’s decision to change the way projects are assessed, with administrators, rather than scientists, deciding which research to back. Added to this is the news that projects that mirror EPSRC priority areas could ’leapfrog’ other projects to secure funding - even if those projects represented better science. ’The EPSRC is not made up of research scientists,’ Clarke says. ’It’s made up of career administrators. They all might be very bright, but they don’t have the scientific understanding, the detailed knowledge required to assess a proposal.’

The council has already earned the ire of chemists by cutting the number of PhDs it will fund by 30 per cent, reducing money for equipment and proposed ’blacklisting’ for academics with a low grant application success rates.

Clarke wants the House of Commons’ Science and Technology Committee (STC) to launch an inquiry into how the council controls the purse strings, while Barrett wants to see EPSRC chief executive David Delpy called to answer questions before the STC.

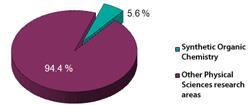

Presently, the EPSRC dishes out £796 million in grants and other research support to the physical sciences each year. Due to the freeze on science funding until 2014 - the result of a government cost cutting drive - its budget is set to fall by 12 to 15 per cent. Synthetic organic chemistry currently receives a relatively large slice of this funding - 5.6 per cent or £44.4m.

Barrett says that what alarmed him most was how decisions were being made. Barrett and Jim Thomas, a synthetic chemist at Manchester University, went to talk to the EPSRC last week about the decision-making process. ’We were utterly horrified by what they told us,’ he says. ’They admitted that there was no consultation whatsoever. Their only contact with the outside world was, to use their word, to "inform". The informing that they carried out was partial - it wasn’t total. They’ve already ranked all the various areas, and they’re drip feeding the community.’

Barrett, who co-founded contract research organisation Argenta Discovery, says that his complaints aren’t sour grapes - he personally receives very little money from the council. He says that synthetic organic chemistry is the lifeblood of many of the UK’s high-tech industries, such as food production and security, electronics and drugs. With chemistry recently shown to contribute £258 billion to the UK’s GDP in a joint EPSRC-Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) study, the letter states that the EPSRC’s decision is ’very short-sighted’. ’I have no problem with synthetic organic chemistry taking a hit,’ he says. ’What I object to is it taking an extra large hit because of decisions by people who we believe are not qualified to make these decisions.’

David Phillips, president of the RSC says: ’We are concerned that there was no extensive consultation...some members of our science, education and industry board had the chance to comment on the process used by the EPSRC but no specific details or likely recommendations on funding issues were shared.’ He adds that the council’s decision-making process need to be more transparent and the people making the decisions need to be known.

In a statement released in response to the letters the EPSRC said: ’Synthetic organic chemistry has received a greater proportion of EPSRC support than most other areas in our physical sciences portfolio in recent years and we cannot sustain this level of funding.’ It claims it consulted widely with stakeholders, such as Pfizer and AstraZeneca, but admits it did not carry out a formal consultation.

Clarke says that unless the EPSRC changes course the damage will be ’incalculable’, with researchers leaving the country in search of funding. ’I think it will set fundamental research back at least a generation,’ he says. ’We won’t have the resources, we won’t have the manpower and we certainly won’t have the people with the necessary skills to do the research.’

No comments yet