US researchers determine that groundwater contamination at fracking sites is the result of poor waste management and not the fracking process

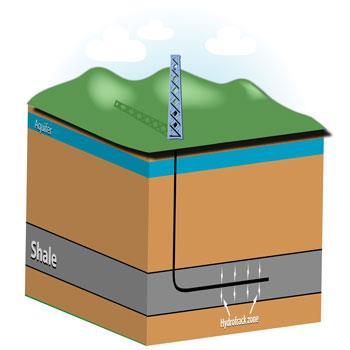

The hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, process - injecting high pressure water, sand and chemicals into a shale bed to release natural gas - is not responsible for groundwater contamination, according to a new study from the University of Texas, Austin, US. Groundwater contamination that has occurred at fracking sites is mostly down to faulty casings allowing the polluted water from fracking to foul groundwater, meaning the risks of fracking are no worse than conventional oil and gas extraction. ’The bottom line conclusion in the states’ areas we investigated . [is that] we found no evidence of actual hydraulic fracturing contaminated groundwater,’ says Charles ’Chip’ Groat, who led the research team.

Part of the reason that fracking has been far more controversial than conventional hydrocarbon drilling, Groat says, is that it is taking place in areas that the oil and gas industry has traditionally shown little interest in. The population density in states like New Jersey, where there have been efforts to impose a state-wide ban on fracking, is much higher than those that have a history of oil exploration, such as Texas. Groat hypothesises that this is causing conflict between communities, who are worried that there is something uniquely environmentally damaging about fracking, and industry, which considers it a fairly standard procedure. He notes that fracking has been going on since the 1950s, but its rapid expansion has fuelled concerns about environmental damage.

Groat says that the team’s aim was to bring together all the available evidence for policymakers. He stresses that the energy institute at Austin received no industry funding and all the money was drawn from university budgets.

Danny Reible, chair of environmental health engineering at the University of Texas, says that much more research is needed on these surface issues. He says it is important to know which chemicals are going into the water used in fracking and that there is an urgent need to develop new technology and ways to manage this wastewater. Groat describes the water that returns to the surface as ’pretty ugly’ as it not only contains the mix of chemicals that help to free the gas from the shale but, having travelled deep underground, it can also be contaminated with a number of other organic and inorganic compounds.

The report also looked at instances of tap water saturated with enough gas to make it flammable - like those memorably seen in the documentary Gaslands. Groat says that much of this is probably natural, although it is difficult to accurately assess this phenomenon as there is little to use as a baseline prior to the start of fracking. ’We really feel hobbled by lack of information,’ he says.

Patrick Walter/Vancouver, Canada

No comments yet