Art conservators have received a helping hand from chemists in dealing with a mysterious grey crust appearing on a painting by Vincent Van Gogh. The layer formed on areas covered with cadmium yellow, which is already known to undergo complex chemical degradation. Now scientists have identified a new deterioration pathway and the results will inform conservation technology.

Staff at the Kröller-Müller Museum turned to chemists for help when they noticed problems developing around the crusty layer. What sparked the concerns was that ‘some areas were becoming increasingly brittle and beginning to flake off,’ according to Geert Van der Snickt from the University of Antwerp, Belgium, the chemist working with the museum. His group had previously reported that cadmium yellow – which is made from cadmium sulfide (CdS) – can oxidise to cadmium sulfate (CdSO4) when paintings are exposed to moisture, oxygen and UV radiation.1 However, because that compound typically forms white crystals, it seemed unlikely that it could explain the grey coloured crust.

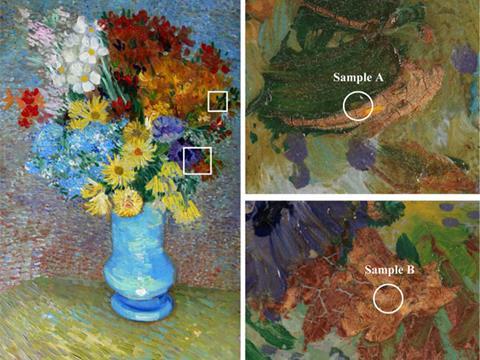

The painting in question, Flowers in a blue vase, a still life by Van Gogh, was painted 125 years ago in Paris. According to Van der Snickt this work is one of only a short series of works by the artist which uses cadmium yellow: the pigment was expensive and Van Gogh found it difficult to acquire when working outside of major cities.

Van der Snickt and his team were passed minute samples of paint by the museum’s preservation experts. These were probed using x-ray diffraction, fluorescence and microscopy techniques using synchrotron radiation.2 They found that the crust contained high levels of cadmium oxalate (CdC2O4). Van der Snickt says that this is strange because oxalate salts are usually only found on outdoor artworks, where there are plenty of organic compounds. ‘It was a pretty surprising find,’ he says. ‘To my knowledge cadmium oxalates have never been seen on a painting before.’

The source of the oxalic acid needed to form the salt is not yet resolved, but Van der Snickt thinks it originated in a layer of varnish which was applied to the painting at some point during its life – probably as an early attempt at preservation. On the rare occasions he has encountered oxalate salts on paintings they have ‘always been close to an old varnish’.

Van der Snickt hopes that the work will help conservators decide how to better preserve Flowers in a blue vase. ‘Paintings are still often cleaned with a [cotton] Q-tip soaked in water,’ he says, but better knowledge of the chemicals in the painting will help to develop better preservation techniques.

The work might also have wider significance. Aviva Burnstock is head of technology and conservation at the Courtauld Institute of Art, UK and she agrees that the new findings could inform conservators and that they are interesting because there are ‘few opportunities to apply sophisticated new analytical methods to study paintings’. Burnstock emphasises the difficult decisions conservators have to make when preserving artworks, taking into account their ‘physical history’ as well as the ‘material, aesthetic and contextual changes’ they undergo as they age. 'Any chance to understand more about how paint degrades is useful,' she adds.

Conservators have already ‘recognised a range of deterioration phenomena in relation to the use of cadmium yellow,’ says Burnstock. In Van der Snickt’s opinion there is probably more to learn: ‘I’m sure that there are even more pathways through which cadmium sulfate can degrade, since every painting has been conserved in a different way. I expect that we will soon start to find other things that cadmium sulfate can produce too.’

References

- G Van der Snickt et al, Anal. Chem., 2009, 81, 2600 (DOI: 10.1021/ac802518z)

- G Van der Snickt et al, Anal. Chem., 2012, DOI: 10.1021/ac3015627

No comments yet