Lead in the atmosphere causes clouds to form at warmer temperatures and with less water

Lead in the atmosphere has a direct effect on how clouds form, according to research by an international team of scientists.

Led by Dan Cziczo at the US Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, the researchers were trying to determine which particles are most effective at triggering atmospheric ice formation, a question raised by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in its 2001 report.

’At first, we were just looking at the composition of the particles that form ice, which predominantly looked to be things like mineral dust,’ Cziczo explains. ’But we realised from our mass spec and electron microscopy studies that these included many man-made components, and the biggest single component that correlated with ice formation was lead.’

Lead was used in experiments in cloud seeding back in the 1940s, but is also released into the atmosphere as a result of other human activities. Much comes from coal-fired power stations, and while tetraethyl lead is no longer added to petrol for the automotive industry, it is still used in light aviation fuel. Despite its removal from petrol, a considerable amount of the old lead is still on the earth’s surface, and blown back into the atmosphere in dust particles.

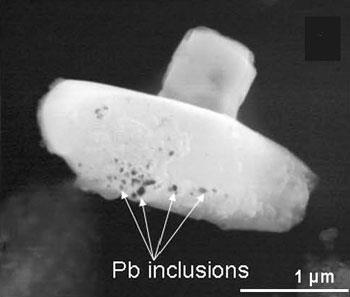

To find out how these lead particles affect clouds, the researchers collected air from a mountain-top in Colorado, and used it to create synthetic clouds in the lab. Half of the ice crystals that formed in the synthetic cloud contained lead, similar to the composition of a real cloud sampled above a Swiss mountain.

To discover whether the lead was responsible for the crystal formation, the US team worked with scientists in Germany and Switzerland to create dust particles that were lead-free or one per cent lead by weight - about the level found in the atmosphere. They found that the air didn’t have to be as cold or heavy with water vapour to form ice crystals around the lead-containing dust particles, findings which suggest that lead reaching the atmosphere through human activities could alter the pattern of rain and snow in a warmer world.

Global climate modeller Ulrike Lohmann from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology put lead into her model at 0 per cent, 1 per cent, 10 per cent and 100 per cent of the dust particles that nucleated the synthetic clouds. Lohmann’s models suggested that with lead, clouds form at lower altitudes, and also allow more of the earth’s heat to escape into space.

’An increase in lead [to 100 per cent] could end up with a global average of 0.8W/m2 of energy going back into space, which would offset global warming to some extent,’ Cziczo says. ’But it highlights how complicated the atmospheric climate system is. Trying to undo what we’ve done to the climate by geoengineering is a very dangerous option as there are so many subtle feedbacks we don’t understand. Before we go tinkering we need to understand things a lot better than we do now.’

Sarah Houlton

References

D J Cziczo et al, Nature Geoscience, 2009. DOI: 10.1038/NGEO499

No comments yet