Archaeologists excavating the remains of a Roman city in Portugal have discovered a rare bronze inkwell filled with the residue of 1st century Roman ink, revealing the ink had a chemical complexity not expected for hundreds of years.

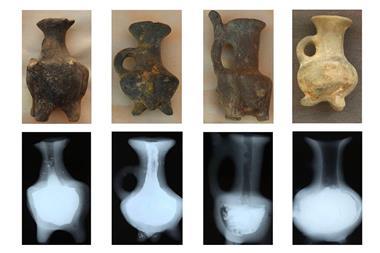

The inkwell was unearthed in early 2023 during work to stabilise an ancient defensive wall at the Conímbriga archaeological site near the modern Portuguese city of Coimbra. It is made in the distinctive rare style of ‘Biebrich’ inkwells, which are named after the site of a Roman military camp in Germany where the first was found in the late 19th century.

But the residual ink inside may be more interesting than the inkwell itself. Detailed chemical analysis shows that the ink consisted of several ingredients, including ash from pine and fir wood; a type of charcoal made from animal bones, called ‘bone black’; and iron compounds made with oak galls – ball-like growths, rich in acidic tannin, that the trees create when specialised gall-wasps lay their eggs in leaf buds.

University of Évora archaeologist César Oliveira, the lead author of the new study, says the ink’s basic ingredients were as expected, but ‘the surprising element is the intentional inclusion of iron-gall ink constituents, creating a hybrid of carbon-based and metal-based ingredients’. The tannin from oak galls combined with iron salts during the ink-making process to create an intense black or dark purple ink. Archaeologists had thought iron-gall inks were invented in by the Romans in the 4th century, and became the most common types of inks in Europe during the middle ages. But ‘our study provides significant evidence that this technology emerged earlier than previously supposed’, Oliviera says, pushing back the invention of these inks by up to 300 years.

Like other Biebrich inkwells, the ancient inkwell from Conímbriga was made with heavy bronze rich in lead and finished by turning it on a lathe. Biebrich inkwells are often associated with the Roman military and administration, and the researchers think it belonged to someone who worked in construction at the site, perhaps as an architect or overseer.

Oliveira says the find was related to either the construction of the wall itself, or to the demolition of an earlier amphitheatre at the same location. ‘What is certain is that the inkwell is directly connected to one of these major building operations,’ he says. ‘It may have belonged to someone engaged in the planning, administration, or supervision of the works.’

The discovery of such a complex recipe for ink at this early time ‘advances debates on the chronology, diversity and transmission of ink technologies in the Roman world,’ the researchers write.

Archaeologist Hella Eckardt of the University of Reading, who was not involved in the latest study, but has researched writing technologies from other Roman-era sites, notes that there have been relatively few writing technology finds in some parts of the ancient Roman world, including Conímbriga. But ‘this paper not only fills in one of these gaps in our knowledge, but adds interesting new information both on the production of these leaded bronze inkwells and, perhaps most excitingly, on the composition of the ink’, she says.

References

C Oliviera et al, Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci., 2025, 17, 216 (DOI: 10.1007/s12520-025-02330-3)

No comments yet