Inaccessible chemistry labs mean the sector is missing out on talent and risks being unable to meet the growing demand for chemical expertise, both in the UK and globally.

A new report from the Royal Society of Chemistry highlights the systemic barriers faced by disabled chemists and calls for a rethink on laboratory design, policy and culture across the industry.

Helen Pain, the society’s chief executive, says the report is not calling for the overhaul of labs at great expense but ‘to apply the same creativity, problem-solving and collaborative spirit that defines chemistry itself to the spaces in which we work’.

Over 400 people took part in the RSC’s research. They acknowledge that progress on disability inclusion has been made in recent years but that there is still stigma, inconsistent support and discrimination that leads to a diminished sense of belonging and job security.

While most survey respondents (disabled or not) work in wet labs, disabled respondents are proportionately more likely to work in computational labs or offices – a shift that may be driven not by choice but by lab design that excludes them.

When asked about barriers in the lab, disabled respondents most frequently cited a lack of awareness of support needs, time constraints and sensory overload that means delayed completion of experiments, longer working hours and increased reliance on assistance. Many disabled chemists have been forced to adapt their career paths to avoid inaccessible lab environments.

This is played out in a range of findings that disabled individuals are less likely to hold senior roles in the sector, and face more and greater obstacles to career progression.

Mark Fox, who researches boron clusters for light-emitting applications at the University of Durham and is profoundly deaf, told Chemistry World that while his barriers aren’t physical and he can work independently, it’s communication which limits others’ appreciation of the range of work he can do. ‘It takes time for me and the other person to get used to each other and do good chemistry.’

Career progression has been restricted too. ‘“Normal” chemists, teach, attend meetings, conferences (network), socialise, interact with other staff, students and technicians which I cannot do,’ Fox notes. ‘[This] means I am stuck on grade 8 while everyone else gets promoted. I simply do not have anyone to be compared with and argue my case for promotion.’ UK universities typically grade academic jobs from 1–10, with 10 being the most senior and usually head of a large department or faculty.

Blaine Fiss, who works on inorganic materials chemistry for clean energy at Dalhousie University in Canada, says that by providing perspectives on a range of disabilities the report helps to make the case for change. ‘It’s very hard to convince policymakers, heads of universities, funding agencies to make these types of changes, if we don’t have the data to back up the claims.’

Fiss has cerebral palsy and finds his biggest challenge has been equipment accessibility, such as the high test tube loaders on NMR spectrometers. He argues that having more accessible labs and equipment will ultimately benefit all lab users as they inevitably get older.

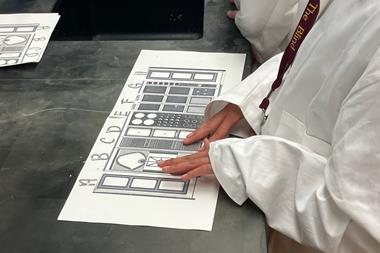

In calling for accessible lab design, the report makes a range of recommendations including providing clear guidance to disabled lab users for getting adjustments made, having non-disabled lab users take part in disability awareness training, share learning across departments, and for policymakers to establish minimum accessibility standards and support upgrades.

‘In my future career,’ says Fiss, ‘I’d love to see a chemistry lab where the design of equipment and the lab layout is not something that we have to think, do I pick option a or option b? I just pick the standard.’

No comments yet