If the future is electric, then the world needs many more batteries. To triple renewable energy, as 133 countries pledged to do at COP28, battery storage capacity must increase six-fold by 2030, while the demand for electric vehicle batteries will grow seven-fold, according to the International Energy Agency. The demands of different applications and raw materials limits, alongside concerns about supply chain security and safety are all pushing the industry to develop new battery chemistries.

Solid state and sodium-ion batteries are advancing rapidly but also in the running are lithium–sulfur, lithium–air, potassium-ion and aluminium-ion batteries.

But experts are warning that the advances are so rapid they are outpacing researchers’ ability to understand and gauge their safety risks. What’s more or less safe is a nuanced question, because many variables have to be considered.

While different chemistries each have advantages and disadvantages in terms of lifespan and energy density, ‘the important thing is that we understand what they are, and that the people that are going to be exposed also understand what they are’, says Donal Finegan, a scientist at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) in the US. For example, first responders need to know what gases are produced during a car battery fire.

‘When you’re testing at the materials level, you get insight into how they would behave, but at the pack level it’s a tricky question because behaviour changes with scale,’ adds Finegan. How a battery has been used, as well as its age, also affects its ability to withstand thermal or mechanical abuse.

Even seemingly minor changes, such as decreasing the cobalt content of the cathode in lithium nickel manganese cobalt (NMC) batteries, can have a detrimental impact on reaction kinetics, making a cell more hazardous, Finegan explains.

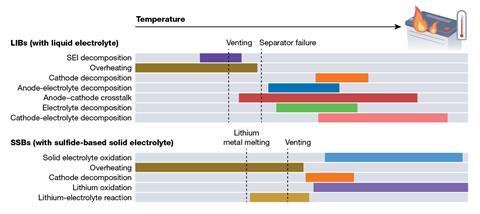

Thermal runaway and fire risks in emerging batteries

During a fire, sulfur-based batteries will produce toxic hydrogen sulfide, while some sodium-ion and potassium-ion chemistries can produce hydrogen cyanide or hydrogen fluoride during thermal runaway. Another overlooked area of research, says Finegan, involves particulate emissions in battery fires. ‘While the manufacturers might understand the nature of the particulate, the community doesn’t, and that’s a major problem. We need to do more experiments and characterisation to inform first responders and give regulatory bodies the data [to] make informed decisions on what PPE [first responders] should wear,’ for example.

While lithium-ion technology continues to evolve in an effort to increase battery lifespan and capacity, even today’s chemistry is not fully understood.

In early November, Stellantis recalled some plug-in hybrid Jeeps and SUVs after reports of several fires. The batteries were made by Samsung SDI, which said that ‘the most likely root cause is separator damage combined with other complex interactions within the battery cells’.

‘I blow up batteries of all sizes, right the way up to full packs … and every time we learn something new – as do the battery manufacturers,’ observes Paul Christensen, an expert in lithium-ion battery safety at Newcastle University. ‘The problem you’ve got is that you cannot extrapolate from cell level to module level, or from module level to pack level, or from pack level to electric vehicle.’ He argues that there’s a need for new state-of-the-art facilities that can test not only lithium-ion batteries but the new generation of batteries coming through.

Phoebe O’Hara, who leads on clean power at the Energy Transitions Commission, a coalition of stakeholders across the energy sector, notes that ‘lithium has had 20 years of innovation and development [as well as] multiple accidents and incidents to learn from. Sodium and solid state are just at the start of this journey, and they’re going to have to go through the same cycle.’

New solid-state technology offers higher energy density and faster charging. It’s so named because it does away with the flammable liquid electrolytes that are the mainstay of today’s batteries – promising a lower risk of thermal runaway.

In their place are polymers such as polyethylene oxide, and inorganic solids including sulfides and oxides. But there are other changes too: having a solid electrolyte does away with the need for a separate insulating layer between cathode and anode, and the anode is made of lithium metal rather than carbon or graphite.

‘We’re turning to solid-state batteries largely because they avoid many of the safety concerns tied to liquid electrolytes, including thermal runaway,’ observes Sylwia Waluś, a battery technology expert at the UK’s Faraday Institution. ‘But “safer” doesn’t mean “risk-free.” These systems still hold a lot of energy in a tight space, and they need to be handled with that in mind.’

Recent research in France, on solid-state cells that are not commercially available, found that under high temperature and pressure conditions, thermal runaway did occur because of far higher heat flow than in liquid electrolyte cells. However, half as much gas was released as with liquid electrolyte cells.

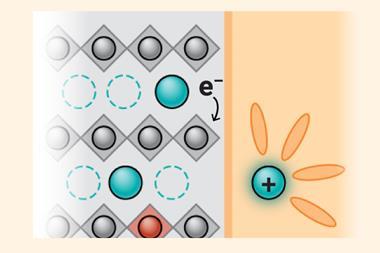

Solid-state cells can also be vulnerable to the formation of dendrites. These are needle-like structures that form during charging and that can cause short circuits. Avoiding their development is a hot topic of research.

And while solid-state batteries should, in theory, be safer, Waluś notes there’s a dearth of quantitative data on how much safer solid states actually are. ‘If something does go wrong, what exactly are the risks? Which gases are released during a failure event, and how do they behave? And if a fire occurs, how intense can it become?’ she asks. That’s a gap the Faraday Institution is trying to fill.

Car makers announce next generation battery plans

Its efforts are timely because car makers are already announcing plans for solid-state battery powered vehicles. Toyota expects to be producing them in 2027–28, bringing longer ranges and faster charging times. Stellantis says it will introduce lithium metal quasi-solid-state batteries made by US firm Factorial Energy, into a demonstration fleet in 2026.

Sodium-ion batteries are finding their initial applications in energy storage, where lifetime operating cost, rather than weight or volume, is the key factor. China is leading the way with the world’s largest sodium-ion energy storage systems.

The world’s largest battery maker, CATL, says its fast-charging sodium-ion batteries will be in vehicles next year. Sodium-ion batteries are viewed as a drop-in technology because they can be made using the same processes and equipment as lithium-ion batteries. CATL is also integrating both technologies into one of its battery systems for EVs, to maximise the benefits of each technology.

Although sodium doesn’t yet match lithium-ion batteries for energy density, it is abundant and costs less to extract. Sodium-ion cells can use aluminium as a current collector at both cathode and anode, delivering savings over lithium, both in terms of weight and cost, suggests Robert Armstrong, who is working on novel electrode materials for sodium- and lithium-ion batteries at the University of St Andrews.

It’s claimed that sodium-ion batteries can be fully discharged for transport and maintenance. This would be an advantage as short circuits in lithium-ion cells during transport have led to fires and explosions. However, Armstrong says it remains to be demonstrated that this is a universal truth for any sodium-ion cell.

In another Faraday Institution project, researchers are investigating the safety of sodium-ion cells sourced online, validating their chemistry and evaluating their response to abuse tests such as nail penetration. The aim is to support technology development and subsequent certification by assessing the so-called ‘state-of-safety’, which could provide early warning of thermal runaway, for example.

With end-of-life battery safety in mind, the EU has developed a digital battery passport in the form of a QR code, which will be required on batteries from 2027. It will provide a digital record of battery components such as materials used in the cathode and anode, hazardous materials and recycled content. The passport is primarily designed to improve traceability of materials and recyclability for a circular economy.

Knowing the chemical components, ‘you can assume a structure so that will make handling really helpful’, suggests O’Hara. ‘Where it will be harder is if you’ve got an ignition or a fire and you aren’t able to scan that battery. But for mechanics and understanding the broader safety mechanism, this is probably the best level of transparency at a global scale that we’ve seen so far.’

International technical standards that agree on battery testing are formed by consensus, explains O’Hara, and will take time to update as new chemistries evolve. Those standards are chemistry agnostic, but testing protocols will have to be updated to cope.

The NREL team observes that there are deficiencies in present lithium-ion battery testing standards, such as the chemical hazards of gases or particulates that get ejected during failure. New tests will be required, for example, to assess the reaction kinetics of next generation battery cells.

Company announcements frequently tell us that new technologies offer enhanced safety, but researchers want to understand the why and the how of such claims. ‘In batteries, safety is the one key performance indicator that allows no trade-offs: any lapse can have far-reaching consequences,’ says Waluś. But ‘because industry rarely has the time or resources to investigate these fundamentals, collaboration with academia is not optional – it is essential’.

Update: The name of the Faraday Institution was corrected on 15 January 2026.

No comments yet