US scientists have come up with a system to assess whether a chemist's latest synthetic product is an endocrine disruptor – a chemical that interferes with hormone regulation in animals and humans.

As industry seeks replacements for endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), such as bisphenol A and some flame retardants, it often discovers that the replacements are no better, and sometimes worse, than what is being replaced. This is because the replacements have been designed using the same flawed tools as their parent chemicals and because of the lack of adequate EDC testing. Now, a team led by Pete Myers, chief executive and chief scientist at Environmental Health Sciences, Virginia, has come up with a way to address this using a system they call TiPED (tiered protocol for endocrine disruption).

TiPED detects endocrine-disrupting action in new chemicals. The system consists of five testing tiers ranging from broad in silico evaluation up through specific cell- and whole organism-based assays. ‘It’s a voluntary programme to be used by chemists, with the help of environmental health scientists, as they work with new chemicals in the lab before they move into the market,’ Myers explains.

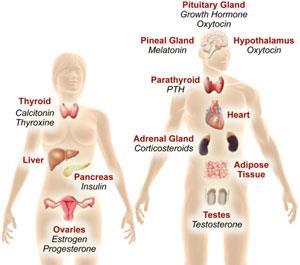

Most of the assays used in current regulatory processes are decades old and the process for updating them is laborious, says Myers. Also, current tools such as quantitative or structure–activity analysis and high-throughput screening using in vitro assays do not address the complexity of the endocrine system. TiPED, by contrast, is designed to evolve as the science on EDCs develops and it broadly interrogates the endocrine system for EDC impact, he adds.

Tiered trapdoors

At each tier, the assays determine whether sufficient evidence is available to conclude that the chemical is not an EDC. If tests for the chemical are negative on one level, it can move to the next, more stringent tier. This saves money and resources by catching serious problems early, Myers says. If the tests are positive, then the chemist has a choice: to stop working on the chemical or redesign it using information provided by the assays.

EDCs affect male and female reproduction and have been linked to cancer, neuroendocrinology problems, thyroid dysfunction, obesity and metabolic disorders, among many others. They are widely used in consumer products and as agricultural and industrial chemicals so exposure is common. As a result, businesses are searching for ways of eliminating endocrine-disrupting characteristics from their products. The Endocrine Society – the world's largest scientific and medical association focusing on how hormones work and how to treat hormone-related diseases – has identified EDC action as one of their biggest health concerns, says Myers.

But the question remains: how could the system be implemented and where would it be based? ‘We are exploring several options that include hosting by a university or starting a not-for-profit or company. It is even possible that government agencies may become partners with us in offering this service to chemists and chemical companies,’ says Myers.

‘This is a thought-provoking paper that should prove useful for chemists in industry, academia, non-government and government institutions,’ says Retha Newbold, head of the developmental endocrinology section in the laboratory of molecular toxicology for the National Institute of Environmental Health Services, US. ‘Some may consider the paper to be too green or to have too much of an environmental agenda; however, the proposed tiered testing for endocrine-disrupting substances could prove cost-effective and economically profitable if it results in less regulation because chemicals are developed that are inherently safe from their inception.’

No comments yet