The international competitiveness of UK chemistry may be damaged by funding cuts, department heads warn

Chemistry in the UK is in danger of falling behind its international competitors as a result of a squeeze on funding for vital lab equipment, according to chemistry department heads. Spending on infrastructure by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) - the main grant funder for chemistry - is to be cut in half. And there is little faith among departmental heads that the Council’s primary solution - sharing equipment - comes close to addressing the problem.

’I think it’s inevitable that we will be less competitive in five years’ time if we’ve halved our capital spend over that period,’ says Matthew Davidson, associate dean, science and head of the inorganic chemistry group at the University of Bath. He adds that it’s difficult to see how equipment sharing can drive down costs as universities are already sharing facilities wherever possible.

Derek Woollins, head of the school of chemistry at St Andrews agrees. ’It’s just awful. We cannot underestimate the severe stress this is going to put us under. I think you can cope with an odd year, a blip, but if [the cuts are] sustained for any significant amount of time then our international competitiveness will fade away.’

Cutting deep

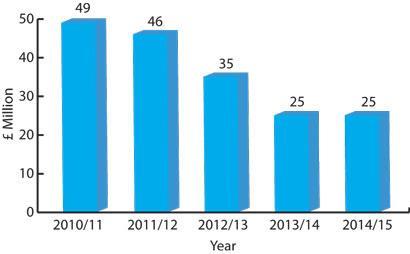

As part of the settlement imposed on the research councils by the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, the EPSRC will see its capital funding halved from ?49m this year to ?25m by 2014-15. The cuts are part of the government’s austerity drive to tackle the budget deficit.

An EPSRC spokesperson says: ’All research councils are facing a 50 per cent reduction in capital budget, and this will have the greatest impact on those councils, including the EPSRC, who currently fund the largest amount of equipment.’ Some of the other councils, such as the Science and Technology Facilities Council, may be able to offset the cuts by making operational savings at the institutes they run. But this will not be an option for the EPSRC, which does not have operational control of any research institutes.

In a bid to hold down costs the EPSRC will only provide half the funds for new kit costing between ?10,000 and ?121,588 - the rest will have to come out of departmental budgets. For equipment costing more than ?121,588 - a figure derived from EU procurement thresholds - labs will have to make a business case detailing its contribution to the economy. There will, however, be money available to cover transport resulting from equipment sharing.

Woollins, who is also a director of EaStCHEM, which organises equipment sharing between St Andrews and Edinburgh University for microanalysis, x-ray diffraction and glass blowing, among others, is sceptical that substantial savings can be made by sharing facilities. ’I think the EPSRC are right on one level,’ he says. ’You want to make sure that all your equipment is fully utilised - you don’t want equipment sat idle. But I don’t think there’s much equipment sat idle in chemistry departments.’ Nevertheless, he says that EaStCHEM is not about ’saving a few hundred quid’, it is about improving access to facilities.

The University of Birmingham has also set up significant collaborations in the region. Jon Preece, head of the school of chemistry at Birmingham, says that these collaborations bring economies of scale to research - saving universities’ money - but that the biggest advantage is the exchange of ideas and skills. ’The long term effects of disinvestment nationally in the academic sciences and the engineering base cannot be good for UK PLC,’ Preece says. ’However, putting my optimistic hat on, I would hope that such equipment sharing will bring complementary groups of academics together that might not have met.’

Antiquated equipment

Department heads are also concerned that after four years of austerity the UK’s chemistry infrastructure will be getting antiquated. ’Quite a lot of us are already sitting on kit that is not brand new,’ says Christopher Whitehead, head of the school of chemistry at the University of Manchester. ’So we already have issues about ageing equipment that isn’t state of the art and is getting quite expensive to maintain and support.’ He describes the situation as a ’time bomb’, saying much of the equipment in the department is over 10 years old. He foresees a situation five years down the line when the research councils will have to step in and inject new cash into departments so they can update their facilities. Something similar occurred in the late 1990s when the Joint Infrastructure Fund was put together and distributed ?750 million to repair, refurbish and upgrade facilities across the country.

’As that equipment becomes obsolete, it’s probably inevitable that we will be seen to be less competitive [internationally],’ says David Phillips, president of the RSC. ’If you can’t compete with the best, then you rapidly lose your position and getting back from that is really difficult.’ He warns that chemistry departments may shrink without the appropriate support. He foresees a future where smaller departments will have to carve out niches for themselves so they can remain competitive with larger, better funded faculties. Whitehead agrees: ’I think the world class work will continue. But it will probably be concentrated in a smaller number of institutions where there is critical mass and critical mass does include appropriate infrastructure.’

Woollins describes the EPSRC’s policy of funnelling money into medium-sized equipment as ’worrying’. He says the tender process for new equipment is unimpressive and lacks scientific rigour. ’There’s a feeling that the EPSRC is trying to keep these medium sized facilities going because it wants to be able to show the government that we still have state of the art [facilities]... but in the current climate it is not clear to me that that represents the best value for money to sustain the community.’

Woollins is also critical of the way the EPSRC operates. ’I think the EPSRC is broken. I think we should just close it completely and distribute the money under the REF algorithm.’ He says that one of the biggest problems with the EPSRC is that it attempts to direct science and influence outcomes without having the technical or scientific know how of other funding bodies, such as the US’s National Science Foundation. Other heads of chemistry are happier with the way the Council operates, acknowledging that it has been dealt a difficult hand by the government.

Another problem facing the chemistry community is that they have been left in funding limbo; they are unsure how much money the EPSRC will provide and whether universities will have the funds to fill in the holes. ’Universities like Bath and others want to do world class science and are investing heavily in world class science but this is an uncertain period... People still don’t know what the funding landscape is going to look like in a year’s time,’ Davidson says.

UK chemistry will be able to weather the cuts in the short term, Phillips says. ’There has been a considerable amount spent in the last five years by the Labour government so I think there has been an investment in equipment that will tide us over, but not for more than five years.’ For now it appears that it will be a case of wait and see how the funding landscape will evolve. ’We’ll know 10 years from now,’ Woollins says. ’I think the chances are [these cuts] will have an impact. You can’t publish in the highest impact journals unless you’ve got well characterised compounds.’

Patrick Walter

Interesting? Spread the word using the ’tools’ menu on the left.

Also of interest

Science budget frozen in spending review

20 October 2010

The UK’s science budget has been frozen until 2014 and higher education funding will bear the brunt of deep departmental spending cuts

Vince Cable: science cuts are coming

08 September 2010

Only research that is academically outstanding or has commercial appeal should be funded says UK business minister in first speech on science

No comments yet